Rabbi Dov Applebaum argued—quite eloquently, he thought—for keeping the spaceship to its original flight plan. After all, there were Jewish children on Orion Station who needed Torah lessons before their upcoming B’nai Mitzvah. And yet the AI refused to listen to him and instead plotted a new course towards the distress signal on Rigel-7.

When the AI stated that intergalactic law compelled them to answer a distress call, Dov might’ve kept quiet—he wouldn’t actually have kept quiet, but he might have—but when the fakakta computer started citing Jewish law, Dov had to object.

“True, Leviticus says not to ‘stand idly by the blood of thy neighbor,'” said Dov, “but there are many interpretations of the Jewish law around distress signals. For one, what is a neighbor, galactically speaking?”

Dov could have discussed this for days, turning the argument about so that every angle of interpretation caught the light. But he only had hours before landfall and the AI had stopped actually listening anyway. Dov was used to that. His students throughout the galaxy didn’t listen, so why should his ship? Dov tried to imagine the Jewish children on Orion Station wailing and rending their garments over the delayed arrival of their favorite rabbi, but it was easier to imagine them eating synth-pork and forgetting what it meant to be Jews.

To add to Rabbi Dov’s woes, as his ship entered orbit and prepared to descend to the surface of Rigel-7, the Rigelian ambassador Cho’sun called on the viewscreen to forbid Dov from landing.

The spider-like Rigelian spoke its own language, which sounded to Dov like Coney Island being picked up with little warning and shaken. Luckily, Dov had a universal translator, a small black box clipped onto the upper sleeve of his flight suit, loaded with an AI that had been trained specifically to Dov’s native language. The box seemed to hum and clear its throat before translating.

“Listen, schmuck,” said the Rigelian through the translation box, “we have no laws to protect outsiders and you’ll just have to live with the consequences.”

Dov glanced at the translation box skeptically and tapped at it with one chewed nail. He couldn’t hear any loose parts in there—and if there were, what could he do about it?

“You hear me, schmuck?” Cho’sun waved its anterior arms in emphasis.

“Ah,” said Dov, as he attempted to stroke his red-brown beard thoughtfully, as his teachers had done and their teachers before them. The effect was rather ruined by his beard’s tendency to float up in microgravity, the curly mass haloing his jaw. “But you see, Ambassador, I am not landing—the ship is.”

Cho’sun made a sound like a garbage disposal chewing up dinosaur bones. The universal translator rendered this as laughter at first and then clarified: “Dismissive laughter.”

“Ambassador,” said Dov, “intergalactic law demands that distress signals be answered by the nearest available ship.” Even if that ship was a weaponless family transport that currently held no family, just Dov and his collection of Judaica, including a parchment Torah in a chased silver case all the way from Earth. That treasure he rarely brought out: only for brief ceremonies and never while his people were noshing.

“Universal law, shmuniversal law.” The ambassador flexed its claws, which might have been body language for emphasis or negation or something else entirely. Dov had skipped taking xeno-linguistics in college and the translator had its limits. “And in any case, Mr. Bigshot, we plan to take care of our own distress call, thank you very much.”

“Ah, so there is nothing to be distressed about?” Dov looked over at the terminal where he imagined the AI to be, a slight air of triumph in his raised eyebrow.

“Nothing at all distressing,” agreed Cho’sun. “As soon as we find them, we will kill off the entire unclean species that is sending whatever call you are receiving.”

Dov grimaced like he’d tasted a bad piece of whitefish. “It sounds, Ambassador, like you are speaking of genocide.”

Insofar as a spider can smile, the ambassador did. “Aha, now you understand.”

Dov’s bad fish expression deepened and he sighed. He couldn’t see any way to avoid landing on Rigel-7. He raised his hands and shrugged, the ancestral Jewish gesture for “What can I do about this? Nothing.”

Even the ambassador, who had probably never met a Jew before, seemed to take Dov’s meaning. Its voice took on a husky edge: the Empire State Building being scraped the length of Long Island. “We will cleanse Rigel-7 of this degenerate species and if you interfere, your life will be forfeit, schmuck.” The viewscreen went dead, the communication cut.

After a long moment of sighing, Dov flipped on a tablet, calling up commentaries on mediation by the most esteemed rabbis, as well as accessing a brief summary of the Rigelians. Their description—violent, xenophobic—sounded to Dov much like his ancestors’ stories of growing up with the Italians in Yonkers. And hadn’t they made peace there before moving to Scarsdale and Florida?

Perhaps Dov could be the one to bring Rigel-7 into the intergalactic community. He’d rather keep to his schedule and be teaching Torah to ungrateful children on backwards space stations, true, but if he had to make peace between two warring tribes on Rigel-7 and go down in history, so be it.

Perhaps, with his help, no one would die.

***

They were all going to die.

Cho’sun had called these other aliens a “species,” but the ambassador had called Dov a “schmuck,” too, so what did he know? Truth be told, Dov felt less like a schmuck and more like a schlemiel: not the clumsy waiter spilling the soup, but the guy the waiter spills soup on. Only in this case, it was more like the universe itself was spilling soup on Dov.

To Dov, these aliens didn’t seem like a distinct species. For one thing, there just weren’t that many of them, maybe ten total, camped out here in the middle of the green-black jungle. The jungle itself smelled faintly of burnt sugar, like overspun cotton candy, and was lush and thorny. Dov had time to discover the thorns as he hiked a few miles from the only clearing where his ship could land, since this benighted planet hadn’t any spaceport or roads or Chinese food. It was unpleasant, even if the air was breathable and the only large predators here were the man-sized, spider-like Rigelians.

Like the ones standing in front of Dov, asking for help, and not really listening when he said he couldn’t give them any.

“No, I don’t have ray guns on my ship,” explained Dov again. “What should I have ray guns for?”

The aliens talked to each other in voices that sounded like the Long Island Expressway being rolled up and eaten like pastrami, in the same language that Cho’sun used. Not only did they speak the same language and look nearly identical to Cho’sun—the same dark compound eyes, chitinous exoskeletons, and abundant limbs—but they waved away Dov’s well-thought-out arguments with the same motions. Dov wasn’t sure what set these Rigelians apart or why he hadn’t become a dentist with a nice little practice on Mars.

“Given your similarities, why do the Rigelians hate you so?” asked Dov.

Yen’tah, a smaller and slightly reddish but just as horrifyingly chitinous and hairy spider-thing, bristled, rising on its posterior four legs. “I reject your question—we too are Rigelian! It’s divisive speech like that—”

The other Rigelians began to yell at Yen’tah, making even more noise than it did. Dov’s translation box parsed their commingled cries: “hush, sheket, enough already!” Yen’tah made a gesture that Dov assumed was rude among egg-laying, non-binary sentients, but it stopped speaking and a moment later the ones who had shouted Yen’tah down quieted to a low grumble.

“The Kin hate us Other-kin because they do not believe in change and we have changed,” said Buch’ker, who was larger than all the other Rigelians and spoke in a voice that sounded like a Ferris wheel making love to a container ship. Buch’ker cocked its head to one side and then the other, a gesture that indicated thought among the Rigelians. Buch’ker was considering how to explain to Dov, and eventually it said, “We see the world differently.”

“Ah, a philosophical difference,” said Dov. “As a Jew, I have some experience—”

The Otherkin around him cut him off, their bulbous abdomens grumbling. The whole noisy rabble reminded Dov unexpectedly of a congregation held too long at service, with the promised land of cookies and gossip so close.

Buch’ker pointed to one of its eyes, as shiny as new challah, and said slowly, as if to a young child, “We see the world differently.”

After some clarification, with Buch’ker talking ever slower, Dov eventually realized this talk of “seeing the world differently” was the literal truth, as well as a metaphor. As metaphor: whereas the Kin avoided change and only maintained the technology they had inherited, the Otherkin believed change was acceptable, particularly when it would help them avoid extinction. And as literal truth: the Otherkin had experienced a genetic shift that allowed them to sense many different wavelengths. Though as they hadn’t developed a theory of genetics yet, Buch’ker explained this as simply a difference between its family—all the spider-aliens here being closely related—and the other Rigelians.

Also, Yen’tah explained, their thoraxes were smaller or hairier or something, but Dov couldn’t see it.

While Buch’ker explained this, two of the Otherkin scuttled up the trees and began to dismantle their nests high in the canopy overhead. These nests were temporary structures, Buch’ker had said before, put up and taken down as the Otherkin migrated through the jungle, staying ahead of their distant cousins and would-be murderers. A few others began to look up at their nests, realizing that Dov couldn’t help them, that running away would be their only hope. Maybe, if they were lucky, the next starship they called with their distress beacon would be more help.

And if not, more running, more distress calls, and more running.

The original distress beacon was still beeping—Dov’s ship relayed the call to his suit, despite his request to the AI to not do that, please. Dov had even asked the Otherkin to turn off the beacon, fearing that the Kin could track it.

Alas, explained the Otherkin named Gon’nef whose eyes were oddly close together, they had just recently invented the distress beacon and had not yet invented the off switch. A few Otherkin made a noise that seemed like laughter at that.

But Dov decided to leave that topic alone, especially after Buck’ker told him that the Kin had viewscreen technology that operated only on that frequency, but not a lot of other communication technology. The Kin couldn’t track this new signal since they didn’t invent any new technology, just lived with whatever old things they had and never changed.

“This taboo against change, this is taught to the Kin from your Creator or Creators?” asked Dov then, looking forward to discussing comparative religion rather than the first topic the Otherkin had wanted to discuss: ray guns.

“What kind of a cockamamie question is that?” grumbled Yen’tah.

“No,” said Buch’ker, “the Creators didn’t teach anything to the Kin before the Kin ate them.”

But now, with the Otherkin packing their nests and preparing to run, Dov felt rather sympathetic to that distress beacon, calling off into the interstellar night for help that might never come. There was something deeply Jewish about it. Dov could almost imagine the Otherkin as the Israelites of the book of Exodus, under the cruel yoke of the pharaoh.

“I have a plan,” said Dov proudly. “We run.”

“This he calls a plan?” Yen’tah sneered.

“If we run, we can escape,” said Dov, “as long the Kin can’t track our signal.”

***

“We easily tracked your signal,” said Ambassador Cho’sun, as it entered Dov’s prison cell, high up in an ancient tower. “But then you probably figured that out when we caught you.”

Dov turned from the window, where he’d been watching his spaceship’s rocket trail, but after he saw the look on Cho’sun’s face, Dov almost turned back. On a human, Cho’sun’s expression would’ve been called a deep frown, but on a human that expression wouldn’t have exposed so many chitin-brown, needle-sharp teeth.

Dov pulled at his flight suit to try to smooth it out and got his beard caught in the suit’s velcro at the neck. “Ambassador, intergalactic law demands that I be allowed to communicate with my home government.”

Cho’sun ignored him. It placed a black box between them and settled itself into the narrow room as best as it could. To fit here, Cho’sun had to fold and tuck its legs under it, like a spider who had extensively practiced yoga. Like most of the city that Dov had seen—while being carried by angry Rigelians—this room was built to a different scale and shape than these natives. The Kin literally lived in houses made for others who had come before them, which, even for Dov, was taking respect for tradition a little too far.

Cho’sun tapped the black box, paused, then tapped it again, this time harder.

“Ambassador, I demand—”

Cho’sun picked the black box up and held it up to its ear canal and shook it, before placing it down and pressing it one more time, firmly. Dov heard a slight pop, like a jar of garlic pickles being opened. Cho’sun clicked its mandibles, which Dov had learned was the Rigelian way of nodding to oneself. Then it began to talk.

“You putz, I told you not to land and what did you do?” Cho’sun fell silent, staring at Dov.

After far too long a silence, the Rigelian added, “That’s not rhetorical, mister. This is your trial right here, nu? You want we should execute you now? Don’t say anything, fine with me.”

Dov paused stroking his beard, getting it caught in velcro again. Buch’ker had told him the Kin would hold a trial before executing and eating him—more respect for tradition, Dov supposed. He just hadn’t thought his impending death would be quite so impending. Dov considered his situation against the long history of the Jews: this was not the worst situation his people had been in. It was not a very comforting thought.

“You want me to explain what I did?” asked Dov.

“Blockhead! We know what you did—you had the gall to save those unclean things with your…” Words failing it, Cho’sun waved a claw towards the window, towards the rocket trail, a column of smoke in the daytime sky. “They all escaped, so I hope you’re happy with yourself.”

Dov considered for a moment before deciding, yes, he was a little happy with himself. It hadn’t been, all things considered, a bad plan for him to run while broadcasting a signal the Kin could detect on the viewscreen technology, while the Otherkin made their way to Dov’s ship, following a signal only they could detect. Dov had a deep, rabbinical urge for symbolism, which was satisfied by the fact that the signal the Otherkin followed was their own distress beacon, relayed from his ship.

Only now he realized the plan’s tragic flaw: he was going to die. It had seemed so clear—and so righteous—at the time for Dov to be the decoy: if any of the Otherkin were left behind, they’d be immediately killed and eaten. At least Dov got this farce of a trial. Not a long enough trial for people to come rescue him, but at least it was something, right?

“We know what you’re guilty of,” said Cho’sun, “we just want to know why. You can explain yourself. And then, the execution.”

“But what am I really guilty of?” asked Dov, a sudden flash of inspiration rising to the surface of his brain like a matzah ball of the perfect lightness and airiness. “The Rigelians wanted to cleanse Rigel-7 of the Otherkin”—Cho’sun bristled at that word, the tiny hairs covering its body vibrating with anger, no xeno-linguistics degree necessary to read that—”and I have done that. There are no more of… them on Rigel-7.”

“Our world is cleansed,” said Cho’sun flatly, “but we were looking forward to killing them all. And now we have to be satisfied with killing only you. And speaking of that,” and Cho’sun reached out to turn off the black box.

“Wait, I can explain better,” said Dov, half-reaching out to swat away Cho’sun’s claw. He caught himself and steepled his fingers as if in thought. “We Jews have an old saying from the Babylonian Talmud—a book of commentary on our laws—that says, ‘whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.'”

“I do not understand,” said the Rigelian, claw still hovering over the black box.

“Ah,” said Dov, nodding, “you see, it’s a moral calculation that asks us to consider—”

Cho’sun waved him off. “Schmuck, it’s ‘book’ I don’t understand. Whatever those are, we don’t have them and don’t want them.”

But then Cho’sun cocked its head to one side and then the other, the Rigelian gesture for considering.

“And how is one life equal to a world?” asked Cho’sun.

“A lesson like that has to be interpreted,” Dov said quickly. He paused as he heard steps coming up the narrow stairs to his tower cell. The steps were halting and clumsy, the narrow stairs not at all suited to the Rigelian’s sprawling legs. And on top of the click of Rigelian claws, Dov heard something else being dragged, bouncing on each hard step with a clunk. Dov had a moment of vivid worry, imagining them dragging some torture device up to his cell.

Cho’sun had to move aside for the other Rigelians to make their way into the cell and drop what they were carrying in a pile at Dov’s feet. The Jewish children of Orion Station would’ve said it was a torture device, but after wiping away some leaves and mud, Dov recognized it all as his collection of Judaica and teaching materials.

They were dented here and there and all jumbled together—the Seder plate next to the shofar horn, his tefillin straps tangled around Elijah’s and Miriam’s cups, the menorah with one arm bent down, the Torah surfing on a sea of yarmulkes, and a classroom’s worth of tablets, loaded with lessons on everything from basic Hebrew to the most abstruse rabbinical commentary.

“We have only you and all of this,” said Cho’sun, gesturing to the pile. And then, with a little more hope in its voice, it added, “Is any of this edible?”

“No,” Dov admitted, “but I can explain how a life is worth a world.” He picked up a tablet, the least dented and mud-covered, checking that it was still working. He turned it on, flipped to the first page, and turned it to face Cho’sun. “This, here, is the letter aleph, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet.”

Cho’sun looked skeptically at the image of the aleph on the tablet’s screen. “Listen, bubele, no more nonsense—this you call the answer to my question?”

Dov considered that for a moment, before answering. “It’s the beginning of an answer.”

“How long will this answer take?”

For once, Dov didn’t say what he thought—hopefully long enough for a ship to come rescue me—but merely shrugged, hands up, and gave Cho’sun the same answer his rabbis had given Dov back when he was a student. “It takes as long as it takes.”

Cho’sun looked back at the tablet, its head cocked first to one side, then the other. “Oy vey,” it said finally, and then clicked its mandibles. “What comes next?”

© 2018 by Benjamin Blattberg

Author’s Note: The seed of this story was probably planted by William Tenn’s “On Venus, Have We Got A Rabbi!” Not the story—just the title. (Though eventually I did read the story and you might want to check it out, too.)

Ben Blattberg is a software developer, improviser, and writer currently living in Austin, TX, as long as there are no followup questions on any of those facts. His stories have appeared in Tina Connolly’s Toasted Cake, Crossed Genres, Pornokitsch, Podcastle, and Pseudopod.

Ben Blattberg is a software developer, improviser, and writer currently living in Austin, TX, as long as there are no followup questions on any of those facts. His stories have appeared in Tina Connolly’s Toasted Cake, Crossed Genres, Pornokitsch, Podcastle, and Pseudopod.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

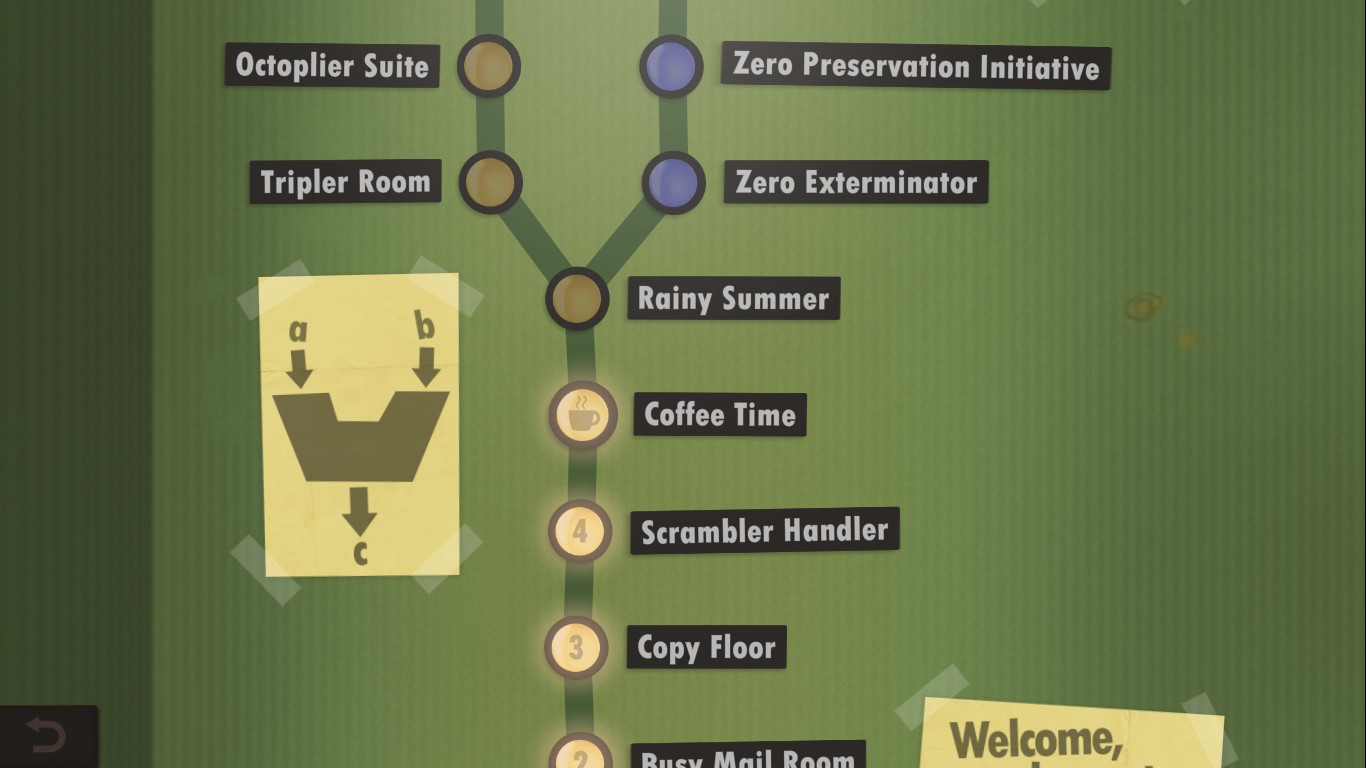

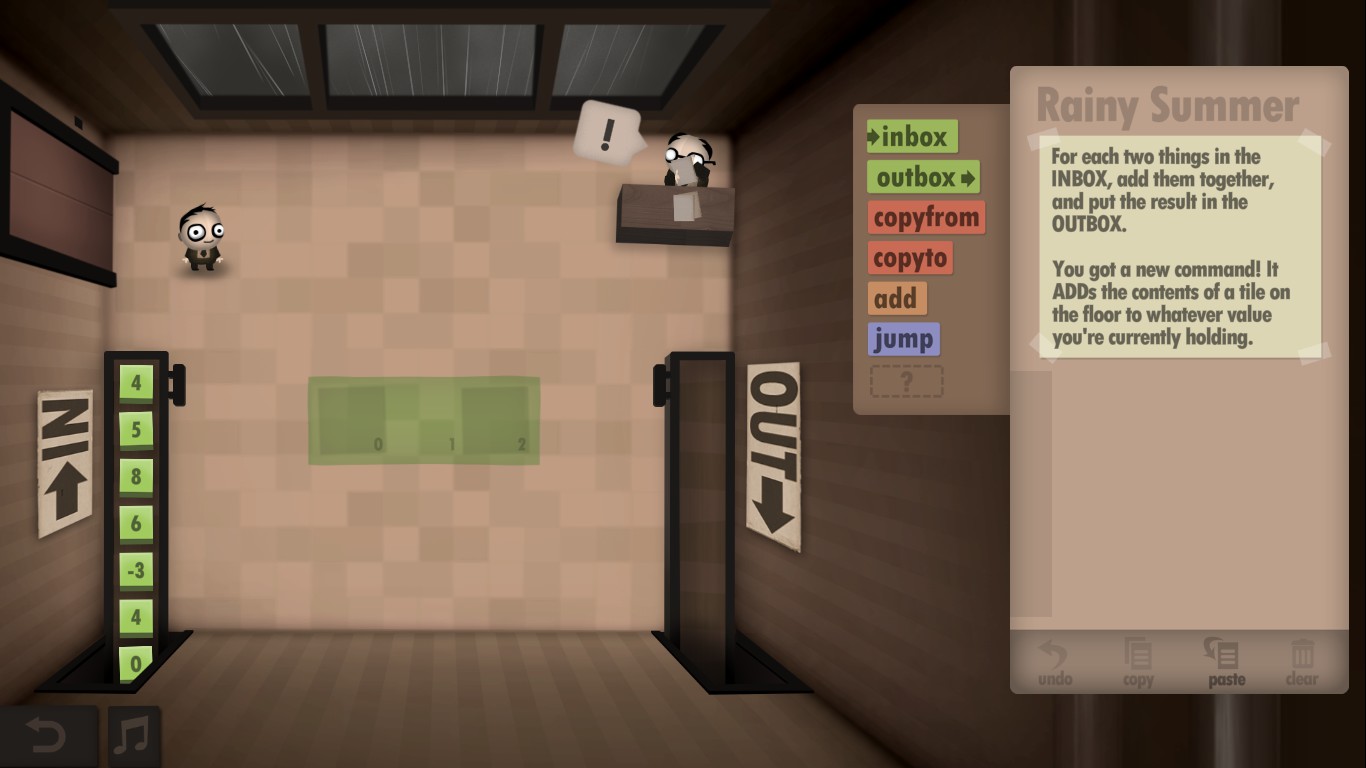

As you work your way up the career ladder you are given tasks by the company dictating how you need to process the input values that come in on one conveyor belt and produce output values to send on the next conveyor belt. When the game starts you have only a couple simple instructions, Input (which grabs a value off the input belt), and Output (which puts whatever value is in your hands onto the output belt). But soon those instructions expand to include add/subtract operators, conditional branches, unconditional branches, storing values in memory, to retrieving values from variables by reference. The challenges get more complex as you work your way up the career path, and there are extra difficult side-branches you can take if you’re up for a challenge.

As you work your way up the career ladder you are given tasks by the company dictating how you need to process the input values that come in on one conveyor belt and produce output values to send on the next conveyor belt. When the game starts you have only a couple simple instructions, Input (which grabs a value off the input belt), and Output (which puts whatever value is in your hands onto the output belt). But soon those instructions expand to include add/subtract operators, conditional branches, unconditional branches, storing values in memory, to retrieving values from variables by reference. The challenges get more complex as you work your way up the career path, and there are extra difficult side-branches you can take if you’re up for a challenge. On each level you can move on if you solve the problem, but you can reach extra achievements if you try to finish optimization challenges. If you can complete the goal under a target amount of instructions in your program, then you will get one achievement. If you can complete the goal with a runtime under a target amount, then you’ll get another. In many cases you will not be able to get both achievements with the same program because in many cases the goals are somewhat counter to each other–reducing the number of instructions means you reuse lines of code as much as possible, but that requires extra jump commands that add to your runtime. The optimization programs will probably be easier if you have a programming background and have covered some material about optimizing code (even though these days most compilers will handle most speed optimizations for you it’s still not a bad idea to understand the concepts). If you want a major hint at optimizing for speed though, search for the term “loop unrolling”–that is the single biggest concept that I used to optimize the first half of the challenges (after that it got harder and I ended up focusing more on just passing the main objective).

On each level you can move on if you solve the problem, but you can reach extra achievements if you try to finish optimization challenges. If you can complete the goal under a target amount of instructions in your program, then you will get one achievement. If you can complete the goal with a runtime under a target amount, then you’ll get another. In many cases you will not be able to get both achievements with the same program because in many cases the goals are somewhat counter to each other–reducing the number of instructions means you reuse lines of code as much as possible, but that requires extra jump commands that add to your runtime. The optimization programs will probably be easier if you have a programming background and have covered some material about optimizing code (even though these days most compilers will handle most speed optimizations for you it’s still not a bad idea to understand the concepts). If you want a major hint at optimizing for speed though, search for the term “loop unrolling”–that is the single biggest concept that I used to optimize the first half of the challenges (after that it got harder and I ended up focusing more on just passing the main objective).