Editor’s Note: This is just one of the items in the Diabolical Pots special issue.

Click here to see the full Diabolical Pots menu.

edited by Kel Coleman

Content note (click for details)

Content note: person living with dementiaWhen Ba begins to lose his memories, he demands we get him a Remote Mouth.

“They’re only available in Asia,” Gerald complains.

“And they’re creepy,” I add, unhelpfully.

But Ba is set. He’s always been on the edge of technology and the Remote Mouth appeals to everything he would like. It is at the intersection of biotechnology (chips in the tongue and the nose) and big data (tastes and smells from all over the world, the data cleaned, encoded, and categorized) and — the quickest way to Ba’s heart — has a stupid name.

My aunts claim they used the Remote Mouth to resurrect their grandmother’s lost vegetarian sheng jian bao recipe. Each of them clipped a sensor onto their tongues and a sensor into their noses and took a selfie, looking like old cyborgs with great perms.

They told the AI what they wanted and the sensors adjusted to give an approximation of what it knew as sheng jian bao. Then they adjusted, long nails tapping at keyboards, until their eyes rolled back and they luxuriated in a sensation that matched that of biting into their grandmother’s sheng jian bao — the soft parting of the lightly sweet white bun, the rebellious crisp at the bottom, and the savory cabbage tossed in sesame oil inside. They sent the saved sensation to a certified Remote Mouth Chef who gave them a recipe they have since framed and hung up next to the sensors of their Remote Mouths. There’s an official Remote Mouth case, a plastic tongue and a plastic nose which the sensors clip neatly into. It hangs on their apartment wall, always smiling.

Gerald is on his phone, no doubt researching the Remote Mouth and if it is just an elaborate scam. He’s all skepticism and collared shirts since he took on his new big city job. It’s because of that job that I ended up moving back in with Ba while Gerald got to stay in the city. Software engineering is a more flexible job, whereas Gerald did not want to start his fancy new role distracted by Ba’s questions or risking him wandering through the background in his cotton pajamas.

“What taste would you trigger?” Gerald asks Ba, his thumb swiping through articles, skimming fast.

Ba clears his throat and slams his mug down. The rickety coffee table shakes. His dentures, placed on an off-white plate, slide forward.

“I will trigger the chop suey of Silk and Spice.”

Gerald and I groan at the same time. But Ba holds up a hand. For a moment, he isn’t an old toothless man who is losing his memories anymore. Instead, as he clears his throat and his eyes focus on mine, he’s our father again, stern and straight-backed before issuing an order — recite the multiplication table, what else will we do on the drive over to school? Or calculate the gas mileage, as he wipes his hands on his jeans and hands us a receipt and a pen.

“If the Remote Mouth can restore that memory, perhaps it can restore others as well,” Ba justifies.

It’s an early-onset form of the disease that has taken over Ba, who is still in his sixties. We should have known from his poor teeth hygiene that there would be other health issues too, possibly striking earlier than expected. Instead, we were ill-prepared, and continue to be ill-prepared. Which is why we give in so easily to his request, since there really is no other semblance of a cure.

We split up the tasks. Gerald contacts one of our aunts to arrange a Remote Mouth to be shipped over. I try to convince Ba to trigger anything but chop suey.

“You’ve had such better food in your life,” I say, thinking about our trip to Italy just a few years ago, where Gerald and I researched the best restaurants for Florentine steak, Venetian mussels, and Roman oxtail. Or northern Vietnam, a decade earlier, chicken pho for breakfast, tropical fruit smoothies, and banh mi to bring onto the flight home. Or even Taiwan, where he grew up, the place Gerald and I have always called the Disney World of food, hopping from fried chicken at night markets to beef noodle soup in alleyways to crab sticky rice in the ballrooms of luxury hotels.

But it’s not just the sheer mediocrity of chop suey compared to all of the other food we’ve had. The Remote Mouth was trained on Chinese food first, having been created by Chinese scientists. Only recently have they started adding the national dishes of other countries to their catalog and no self-respecting country would ever claim chop suey as its national dish.

“Chop suey was always the best,” Ba says. “And all of my best memories were at Silk and Spice.”

I sigh. I should not have bothered arranging those Venetian rowing lessons or the scenic trek through the remote mountains of Vietnam. I should have just dropped him off at the old Silk and Spice building and let him walk home.

Silk and Spice was the name of the restaurant we went to every weekend as kids, in the strip mall just a few turns away from our home. Gerald and I would drag our feet getting into the car — Silk and Spice again? We’d look longingly at the McDonalds we sped past and even at the pizza place whose cheese always upset our stomachs.

We’d file in like prisoners, assigned to the back corner of the restaurant at the large circular table covered in a white tablecloth. A rushed waiter would place a tray of golden crisp crackers and two plates of orange duck sauce, whatever that is, on the turntable in the middle. I’d scoop at the sauce with my crisp, orbs of glistening orange dangling off, while Ba made a show of looking at the menu even though he always ordered the same things — beef and broccoli, hot and sour soup, and chop suey. I’d inevitably drip orange sauce onto the pristine white cloth, the oils spreading slowly.

Later, when Gerald and I moved into the city, when our appetizers consisted of crisp pork belly bao garnished with shining scallion, our entrees of wagyu beef chow fun, and desserts of matcha chocolate chip cookies paired with organic soy milk, we’d laugh and pity our past selves, whose father convinced them Silk and Spice’s chop suey was fine dining.

The worst was when our aunts came to visit.

“Let’s go to McDonald’s,” I’d say eagerly.

“We’re going to Silk and Spice,” said Ba every time.

“But they eat such better Chinese food normally,” Gerald would complain. “McDonald’s–”

“Three chop sueys, please.”

While the adults talked politics and Silk and Spice stayed open just for us, Gerald and I would entertain ourselves by making the grossest mixture we could think of. We’d tear open packets of sugar on the table, their remnants a pile of torn pink paper, and pour the crystals into an unused tea cup. Gerald would pour soy sauce in, dark and gleaming, combining with the sugar in a dark slush. We’d take turns sticking one of the chopsticks in the tea cup and swirling, forming a muddy paste.

During one of these family meals, I was feeling particularly spiteful. Gerald was set to go back to Taiwan with our aunts as a middle school graduation present. But Ba refused to let me go too since it would mean missing two days of class. As everyone else tittered happily about going back to Taiwan and the foods they would eat, I poked at the limp cabbage in the chop suey and wondered if this was what I would be eating for the rest of my life.

Gerald consoled me by trying to make the grossest concoction yet. Sugar and soy sauce mixed together, then Gerald daringly scraped in the leftover duck sauce too. But I went a step farther.

When one of the aunts picked up the teapot and asked if anybody wanted refills, the adults placed their porcelain tea cups on the turntable. I added the cup with our mixture into the lineup as Gerald stared with wide eyes. The cup joined the others, rotated around the table, and was filled with dark tea, becoming indistinguishable from the rest. For the most part, the adults kept an eye on their cups and retrieved them. But I retrieved Ba’s for him, as well as my own cup, and with an easy cross of my arms, swapped them. He didn’t notice, still arguing with his sisters about the Taiwan president.

Gerald hissed at me to swap them back but I helped myself to another serving of chop suey instead.

My father took a sip. I held my breath.

It was like a cartoon. Ba pushed himself away from the table, a brown fountain spewing from his mouth. The spray reached the white table cloth, staining it, then fell all at once, onto the linoleum, the closest thing I had ever seen to blood splatter. And I know this is only my memory distorting things since Ba still had his teeth back then, but I can picture so clearly — his dentures flinging out of his mouth, trying to escape the concoction I set on him.

Gerald was as pale as the tablecloth. I looked anywhere but at Ba. Our aunts stared with their mouths hanging open, chop suey halfway to their mouths, dangling from chopsticks.

Ba lopped a chopstick full of chop suey into his mouth and munched fiercely. He looked between us and his sisters. It could have been bad. But his sisters were stifling laughter and he was too proud to make a scene in front of them. His eyes went to the tea again, the sugar, soy sauce, and duck sauce thoroughly mixed in, then back to his laughing sisters, then back to Gerald, still as a statue, and me, suddenly stuffing chop suey in my mouth like he’d always wanted. His eyes crinkled, anger lines smoothing to laughter even as he tried to furrow them back, his face alternating between stern and amused, flickering like a light bulb.

“Laugh now,” he said, voice cracking at trying to stay serious. “But I will never forget this.”

*

Our aunt ships a Remote Mouth over, due to arrive by the end of the month. In the meantime, she emails us a wall of Chinese text explaining how the Remote Mouth works, as if she can detect Gerald’s skepticism from the other side of the world. We translate it and soon we are reading about taste and smell and how they work together to send signals to your brain, how the hippocampus, the part of the brain associated with memory, has a link to the taste cortex, and how the Remote Mouth chips stimulate different combinations along the taste and smell receptors. There’s a cartoon of a man with his tongue out and his thumb up, a thought bubble with a plate of steaming dumplings inside.

While we wait for the package, I take Ba to the mall for walks where we eat at the food court, beef and broccoli lunch specials over rice, sometimes orange chicken.

“These places never have chop suey anymore,” Ba laments.

“That’s because it’s not good,” I say under my breath.

“This isn’t salty enough,” he says as he scoops saucy rice into his mouth even as I chug water. He pops his dentures out and glares at them, as if they could be interfering with his taste.

“As you grow older, you lose taste buds,” I say. “Maybe the taste buds that liked Silk and Spice’s chop suey are gone now.”

“Impossible.”

At home, he’s gotten into a weird habit of dangling his lower denture out of his mouth, as if he thinks he’s an NBA player getting ready to shoot free throws. Eventually, he started clacking them, jaw chomping, fake teeth bobbing, a sideways smile carved down his chin.

“Ba, that’s gross,” I said the first time. But he hasn’t been able to stop doing it and I stopped complaining because the clicking is a good way to know where he is in the house.

“He made a baby at the mall cry today,” I tell Gerald when I escape for my weekly visit with him in the city. We share a plate of free-range salt and pepper chicken.

“Good old teeth trick?” Gerald asks.

“Leaned right over, cooed at the baby, then pop! Half set of teeth right in front of the baby’s face.”

Gerald laughs but it quickly falls to silence.

“He’s getting worse then,” he says.

“The Remote Mouth might not even do anything for him,” I say quietly. “His memories might be too far gone by then. And I’ll have to hack it to even recognize crappy Americanized Chinese food.”

Gerald drives me home later that night, after a few hours of mindless television. He’s feeling guilty again and is probably going to offer more financial support or to hire a professional caretaker. I’m not in the mood for an argument though, so I ask him to pull over at the McDonalds and buy me some nuggets which I know will soothe his conscience.

“Is this really what we used to beg for?” I hold up a nugget, its thin fried skin separating from its mushy innards.

“Ah,” Gerald says, a glint in his eye. “Your taste buds have grown up. I know what you want.”

He pulls into the next lot over and we order lo mein and stir-fried cabbage. We scarf it down, nuggets forgotten. Gerald’s fortune cookie says he will reconnect with a lost one. Mine says Learn Chinese! 品嚐: taste

All those little boxes in the characters make me think of teeth, of bumps along the tongue, of the tens of hundreds of taste buds in each bump sending signals to my brain. Nuggets are tasty, they say, but this greasy Chinese American food? Those signals travel on well-worn paths, grooves that won’t go away, that are in Ba and Gerald’s brains too, that have been slowly sculpted with each trip to Silk and Spice. I think of the plaque forming in Ba’s brain, blocking off his memories, and wonder if maybe he’s right and the taste signals have a chance of breaking through all that plaque. Or if Gerald and I use the Remote Mouth enough and map out the paths that are still healthy and clear in our minds, we can barrage Ba’s brain with signals until his paths are clear too. And that maybe half of what being a family is about is just about having similar brain grooves.

A few weeks later, at Gerald’s apartment, I’m the first to try the Remote Mouth. A clip in the mouth and a clip in the nose. Gerald is perched on the couch, socks half dangling off his feet.

“Can you please put your socks on properly?” I ask, peeved.

“What’s up with you?” he grumbles, but he does pull his socks on all the way.

“Guess it just reminds me of Ba and his teeth.”

I didn’t mean to make Gerald feel guilty again. But it’s probably why he lets me try the Remote Mouth first. He opens the manual.

“Ready for some beef noodle soup?” He clicks on one of the defaults in the computer program.

It’s good. Really good. Like I’m finally done waiting in a line out the door, escaping from the outside humidity into a pale building with only ceiling fans, still sweating yet ordering a hot bowl of soup. Spiced and savory, beef that melts on the tongue, noodles that make me want to chew to feel its gentle give.

“Let me throw in some preserved veggies,” Gerald says and clicks another button.

And a memory of Ba heaping preserved vegetables into my bowl comes, another trip to Taiwan, where he helped me pick out the scallions from my soup because I hated them back then. The other guests in line glared at us for taking too much time. Ba turned his back to them and made sure to clear my bowl of all offending greens, piling them away and encouraging me to take my time.

Gerald fades the tastes away.

“How could Ba have grown up eating food like this but end up liking only chop suey?” I complain.

“It was the closest thing to home for him back then,” Gerald says.

Ba came to America when he was in high school. It makes me feel lousy, imagining him trying to find food that stimulated the same feelings of home and finding the closest thing in oily leftover vegetables.

Gerald and I switch places. I scroll through the defaults and give him steamed crab.

Gerald sits up afterwards and shakes his head.

“How was it?” I ask.

“I remembered shelling crabs with Ba, picking at every crevice with chopsticks. And when I told him I was done, he inspected my picked-out shells to make sure I actually got all of the meat.”

“He’s the worst,” I say.

“The worst,” Gerald agrees, but neither of us can say it with conviction.

*

When we give the Remote Mouth to Ba, he reclines on his sofa and pops out his dentures.

“I don’t want this getting in the way,” he says, and places his teeth on a plate next to the television remote.

We show him how to use the computer program to adjust both the sensor in the nose and the one in the mouth. I have to alter the program in order for Ba to input a custom taste. His face goes through all sorts of expressions as he tries to send signals down the same paths chop suey would travel down. Gerald brought over a box of takeout sushi which we share. We pile the ginger up for Ba to use as a palette cleanser.

He doesn’t get it the first day. He looks especially upset without his dentures in, his mouth sagging inwards. But we trigger crab and chicken curry for him and he’s happy when he goes to bed.

The second day I’m connecting my computer to the Remote Mouth and feeding extra data in. There’s a sophisticated community around extending the dataset inputting known ingredients and cooking methods. For chop suey, I put:

– bean sprouts, yellowed, untrimmed

– cabbage: splotchy, wilted

– meat: mystery

– garlic: minced

– soy sauce: doused

– sugar: some?

– wok tossed

– cornstarch slurried

But before I’m done, Ba comes in. I don’t hear him coming because he doesn’t have his dentures in. He watches me fiddle before asking if he can try. He shoos me away once he has the hang of it.

Downstairs, Gerald wants to brew coffee but for some reason Ba’s socks are in the coffee maker. And when I roll them up and toss them in the laundry, I find his dentures there, smiling up at me. I pick them up and plant them in Gerald’s suitcase, giving his crisp collared shirt a smile.

Ba comes out of my room triumphant.

“I have it,” he says, holding up the sensors in trembling hands. His eyes crinkle at the ends and he smiles wide and toothless. “Try it,” he says. “See what you think.”

I lie down on the couch with the Remote Mouth, sanitizing them with the included solution. Gerald’s finally got the coffee machine going and I worry the smell will interfere. But as soon as I click in the Remote Mouth, all other senses mute.

It doesn’t taste like chop suey. Ba’s too far gone, I think, or his taste buds don’t map to mine, or he just doesn’t have as many anymore. It doesn’t taste like anything I’ve ever had before, and not in a good way. It’s watery yet burnt, overly sweet but also a bombardment of umami which I did not think could be bad. And just a hint of… duck? And I suddenly see the stained tablecloth, tea mixed with sugar and soy sauce and mystery orange duck sauce, Ba’s flickering face, the aunts laughing, Gerald paling, and my own heart hammering. And his words–

I will never forget this.

I open my eyes and I’m sniffing, tears precarious. He still remembers this stupid incident, is still trying his best, even as Gerald and I fumble but also try our best. Ba is smiling shamelessly. He is looking more pleased with this taste of vengeance than with any chop suey I’ve ever seen him eat. It makes me snort and my tears turn into hiccuped laughter as Gerald looks between us, confused, mug of coffee in one hand. And even after I remove the Remote Mouth everything still tastes gross but there’s no more sushi ginger so I grab Gerald’s coffee and scorch my taste buds. But my taste buds will never forget this moment, of me and Gerald and Ba, of tastes good and bad, of brain pathways grooved into the same patterns across the three of us, and of the unforgettable desire to hold on forever.

© 2022 by Allison King

3510 words

Author’s Note: This story was inspired by my father’s love of chop suey, my grandmother’s denture adventures, and my family’s never ending quest to find where the chef of Silk and Spice, favorite of South Jersey families, works now. If you know, please let us know, so we can move on.

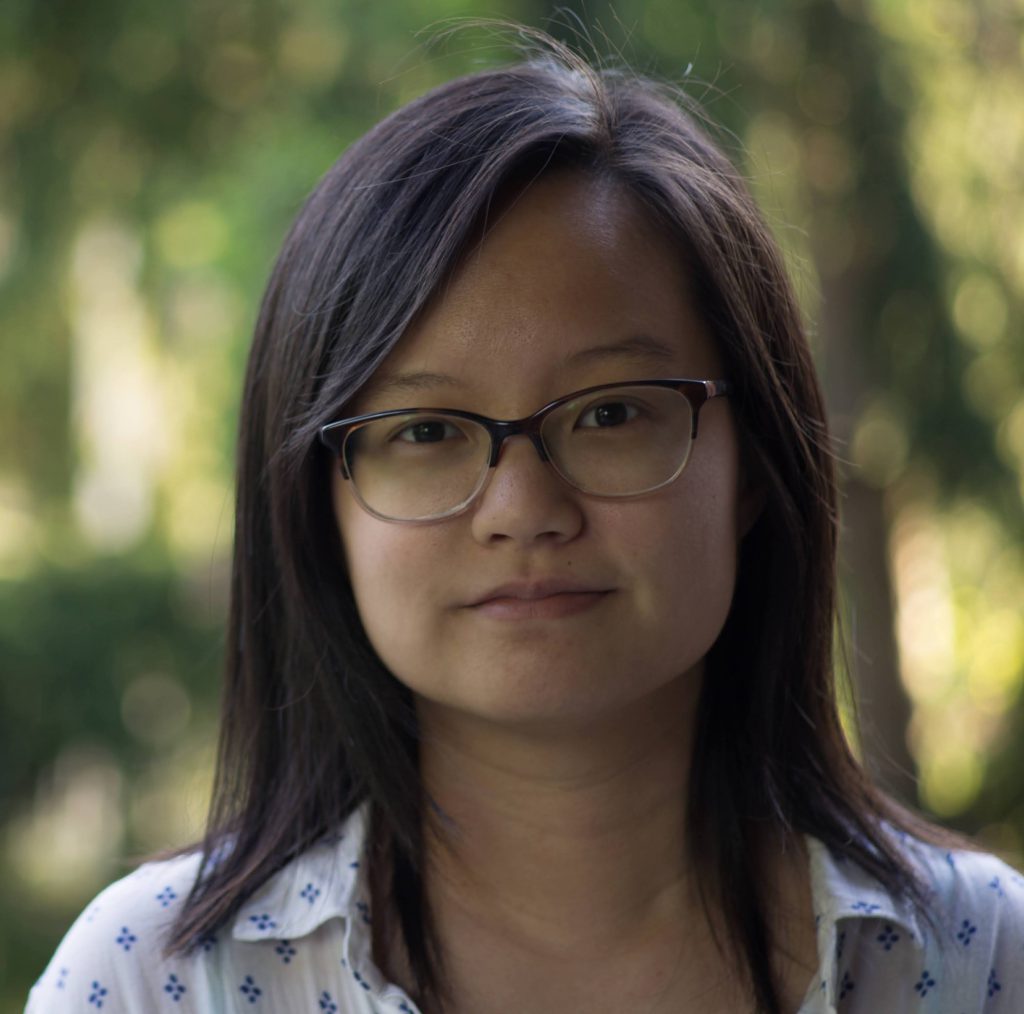

Allison King is an Asian American writer and software engineer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her work has also appeared in Fantasy Magazine. She can be found at allisonjking.com or on Twitter @allisonjking.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

非常感謝! Thank you so much for sharing this!

I heard it on LeVar Burton’s podcast. I was so terribly distracted that my mind kept wandering. When I would come back around to listening the first time I was excited that it was a Taiwanese family story. The second time, I thought I heard about the main character’s 爸爸 not only liking but preferring chop suet and beef & broccoli!

I hit pause. I start to scroll the internet immediately.

“Am I in the middle of wasting my time while some writer pretending to be of Chinese heritage feigns an expertise that is obviously mistaken?” I think. “What Chinese family asks for the leftover scraps as a meal? And 大家 knows that broccoli is an easy way for a restaurant to save some money while filling the customers’ plates.”

Once I find your story and profile, I’m stumped but humbled enough to try listening again, only this time a bit more closely. It doesn’t take long to realize you basically said as much yourself in the telling. But the turn at the end still has me!

Missing my own father may predispose me to a beautiful and funny story like yours. Being a Jersey-born and Jersey-family girl might have me a little biased, but…

…Being human is why I understood this story is worth the time, energy, and heart shared in the writing and the honest listening.

最美好的祝愿和多保重. 💐