written by David Steffen

Congratulations. The October labor lottery is complete. Your name was pulled. For immediate placement, report to the The Ministry of Admission at Grestin Border Checkpoint. An apartment will be provided for you and your family in East Grestin. Expect a Class-8 dwelling.

Congratulations. The October labor lottery is complete. Your name was pulled. For immediate placement, report to the The Ministry of Admission at Grestin Border Checkpoint. An apartment will be provided for you and your family in East Grestin. Expect a Class-8 dwelling.

Papers, Please was released by Lucas Pope in August 2013, a first person multiple ending pattern-matching ethical conundrum game. This is just another one of those games about immigration documentation processing. Exciting, right? Actually, hear me out. I was skeptical, too, but the game came highly recommended. The game is billed as a “dystopian document thriller”.

You work for the government of Aristotska (a country reminiscient of Cold-War era soviet administration), screening people entering the country. Day one is straightforward, because you’ve been told to turn away anyone without an Aristotskan passport. But the government responds to public pressure by starting to allow others through. People start slipping through who don’t belong and the government responds by adding new kinds of documents that you have to check–often checking one document against another for consistent information, checking the sex of the person against the ID (with body scan as a secondary check), scanning for contraband, arresting wanted criminals, etc. You have to pay for food and heat for your family, medicine if your son gets sick, other expenses that you can’t always predict. You get paid for each person you process, but your pay gets docked for making mistakes. The rules change every day, and to support your family you have to be both fast and accurate.

You work for the government of Aristotska (a country reminiscient of Cold-War era soviet administration), screening people entering the country. Day one is straightforward, because you’ve been told to turn away anyone without an Aristotskan passport. But the government responds to public pressure by starting to allow others through. People start slipping through who don’t belong and the government responds by adding new kinds of documents that you have to check–often checking one document against another for consistent information, checking the sex of the person against the ID (with body scan as a secondary check), scanning for contraband, arresting wanted criminals, etc. You have to pay for food and heat for your family, medicine if your son gets sick, other expenses that you can’t always predict. You get paid for each person you process, but your pay gets docked for making mistakes. The rules change every day, and to support your family you have to be both fast and accurate.

That’s what you might call the main focus of the gameplay, but there are quite a few other elements. A revolutionary group is just starting to get their foundations, and because you hold a position of relative importance they want to pay you to make selective mistakes that favor their group. But the Aristotskan government inspector is watching your every move, so you’d better consider very carefully what kinds of requests you want to take. Meanwhile, there are violent attacks on the border which close the office early for the day and which you can help stop. People coming through the gate may make requests of you–helping a recruiter find workers, offering to buy or sell items. The most poignant are ethical choices where a man’s documentation is all valid, but before he leaves the booth he asks you to let his wife through–you soon find her passport has expired. Will you let her through to meet her husband or will you follow orders and turn her away?

There are some moments of levity in the game–mostly around one guy who is gleefully criminal. After a body scan turns up something suspicious, you ask him what it is, and his response is “Is drugs!” But much of the game is quite dark, thinking about what it must be like for all these people trying to cross from one country to another, and weighing the ethical decisions when you’re torn between doing what’s right and what’s legal according to the laws.

There are some moments of levity in the game–mostly around one guy who is gleefully criminal. After a body scan turns up something suspicious, you ask him what it is, and his response is “Is drugs!” But much of the game is quite dark, thinking about what it must be like for all these people trying to cross from one country to another, and weighing the ethical decisions when you’re torn between doing what’s right and what’s legal according to the laws.

There are twenty different endings, depending on the choices you make. The easiest to reach happens when you run out of money–you are thrown in jail for the crime of debt. You can reach other endings depending on whether you support or reject the revolutionaries (and whether you get caught supporting the revolutionaries), and other choices.

There is so much going on in this game, plenty to keep you entertained. Just the core challenge of checking documents is hard enough with all the changing rules and time limit and penalty for mistakes, and then all the ethical choices and storyline branching makes it all the better.

Visuals

Simple 80’s era visuals, but adequate.

Audio

Music/audio that fits the visuals. I like the inarticulate garble the loudspeaker makes when you call the next person in line.

Challenge

This game is moderately challenging with a reasonable learning curve. The first day is easy–just need to check the country name. As the game goes on there are more things to check and more documents which can reveal discrepancy. I got significantly better with practice, but in the later levels it was still a challenge.

Story

Good story. The main objective of the game is to make sure that you and your family survive by processing enough immigrants and making few enough errors that you don’t get penalized. But there are other branches along the way that can lead to different endings. You can choose to support or resist revolutionaries at several points in the story, you can choose to let people through who engage your sympathies or if you will always stick to the policies.

Session Time

Pretty fast. The game auto-saves after each day. The clock is ticking on each day so if you’re not paused the time is slipping away every moment. Some of the days are cut especially short if there’s an attack on the border. You can get a day in with just a few minutes.

Playability

Easy to learn, hard to keep track of all the little details that change from day to day. If you make a little excess cash you can make your life easier by purchasing some booth upgrades that will give you shortcut keys to cut down on mouse interactions.

Replayability

Quite a bit of replay potential here. There are many different endings which you can reach by making particular choices. Each country in the region also has a special token that can be obtained by helping a person from that country, but the path to those are not always obvious either. Your save file lets you reload from any previous day and it keeps track of multiple different branches, so you can go back to day five and make different choices in that day and try to process more people and after you finish that day you can load from either branch.

Originality

Very, very original. I never would have thought that a game about processing immigration paperwork could be anything but extremely dull, but the game both provides challenge in the manner of attention to detail, but also various ethical conundrums.

Playtime

I’ve spent about 8 hours playing this game, I think I finished a full run through in 5-6 hours, then went back to replay some different paths.

Overall

The list price on Steam is $10. Very reasonable price. Great game. Easy buy.

What superpower would you choose? Most classical superpowers are awesome for combat, but not all that practical in day-to-day activities. Super strength? Guess who’s going to get asked to help everyone move. Fireballs–handy in limited context, maybe, but modern life doesn’t require a lot of fire-lighting on a day to day basis. Metal claws–wouldn’t need to hold pocket knives but you could never get through airport security.

What superpower would you choose? Most classical superpowers are awesome for combat, but not all that practical in day-to-day activities. Super strength? Guess who’s going to get asked to help everyone move. Fireballs–handy in limited context, maybe, but modern life doesn’t require a lot of fire-lighting on a day to day basis. Metal claws–wouldn’t need to hold pocket knives but you could never get through airport security. This is a cause that I am sympathetic to. I know many people who have suffered through depression. Some who are still fighting through it, some who seem to have met some kind of livable equilibrium, and others who have died at their own hand. So, I heartily support the goals of this game. Most of the time I play games just for fun and for mental/dexterity and for no other reason, but I am not opposed to other goals.

This is a cause that I am sympathetic to. I know many people who have suffered through depression. Some who are still fighting through it, some who seem to have met some kind of livable equilibrium, and others who have died at their own hand. So, I heartily support the goals of this game. Most of the time I play games just for fun and for mental/dexterity and for no other reason, but I am not opposed to other goals.

June 7th, 1995. 1:15am You’ve been traveling Europe for a year. While you were gone your family inherited a house from your weird Uncle Oscar and your parents and younger sister Sam have moved in. You arrive at the new house, expecting a warm welcome from you family, but no one’s there. Why? You explore the house as you try to find out what has happened and where everyone is. You are completely unfamiliar with the house, so you don’t know anything about the layout, how rooms are arranged or anything. The game keeps a handy auto-map to help you keep track of where you’ve been. From time to time you discover a clue that points you to look in a particular part of the house, and the auto-map very handily marks the spot for you.

June 7th, 1995. 1:15am You’ve been traveling Europe for a year. While you were gone your family inherited a house from your weird Uncle Oscar and your parents and younger sister Sam have moved in. You arrive at the new house, expecting a warm welcome from you family, but no one’s there. Why? You explore the house as you try to find out what has happened and where everyone is. You are completely unfamiliar with the house, so you don’t know anything about the layout, how rooms are arranged or anything. The game keeps a handy auto-map to help you keep track of where you’ve been. From time to time you discover a clue that points you to look in a particular part of the house, and the auto-map very handily marks the spot for you. Audio

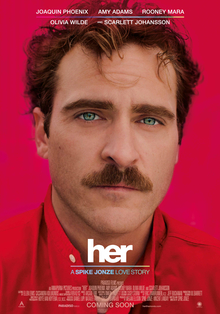

Audio Back in April I reviewed the Ray Bradbury Award nominees for the years as their deadline for nomination approached–I reviewed all the ones I could get my hands on, but there was one movie that wasn’t yet released on DVD–titled “Her” written and directed by Spike Jonze.

Back in April I reviewed the Ray Bradbury Award nominees for the years as their deadline for nomination approached–I reviewed all the ones I could get my hands on, but there was one movie that wasn’t yet released on DVD–titled “Her” written and directed by Spike Jonze.

If you’re interested in the idea of a game that simulates the experience of depression, I recommend instead playing

If you’re interested in the idea of a game that simulates the experience of depression, I recommend instead playing

You work for the government of Aristotska (a country reminiscient of Cold-War era soviet administration), screening people entering the country. Day one is straightforward, because you’ve been told to turn away anyone without an Aristotskan passport. But the government responds to public pressure by starting to allow others through. People start slipping through who don’t belong and the government responds by adding new kinds of documents that you have to check–often checking one document against another for consistent information, checking the sex of the person against the ID (with body scan as a secondary check), scanning for contraband, arresting wanted criminals, etc. You have to pay for food and heat for your family, medicine if your son gets sick, other expenses that you can’t always predict. You get paid for each person you process, but your pay gets docked for making mistakes. The rules change every day, and to support your family you have to be both fast and accurate.

You work for the government of Aristotska (a country reminiscient of Cold-War era soviet administration), screening people entering the country. Day one is straightforward, because you’ve been told to turn away anyone without an Aristotskan passport. But the government responds to public pressure by starting to allow others through. People start slipping through who don’t belong and the government responds by adding new kinds of documents that you have to check–often checking one document against another for consistent information, checking the sex of the person against the ID (with body scan as a secondary check), scanning for contraband, arresting wanted criminals, etc. You have to pay for food and heat for your family, medicine if your son gets sick, other expenses that you can’t always predict. You get paid for each person you process, but your pay gets docked for making mistakes. The rules change every day, and to support your family you have to be both fast and accurate. There are some moments of levity in the game–mostly around one guy who is gleefully criminal. After a body scan turns up something suspicious, you ask him what it is, and his response is “Is drugs!” But much of the game is quite dark, thinking about what it must be like for all these people trying to cross from one country to another, and weighing the ethical decisions when you’re torn between doing what’s right and what’s legal according to the laws.

There are some moments of levity in the game–mostly around one guy who is gleefully criminal. After a body scan turns up something suspicious, you ask him what it is, and his response is “Is drugs!” But much of the game is quite dark, thinking about what it must be like for all these people trying to cross from one country to another, and weighing the ethical decisions when you’re torn between doing what’s right and what’s legal according to the laws.