Content note (click for details)

Harm to animalsedited by Hal Y. Zhang

Sarti, P., & Ricci, M. (2026). “High-efficiency capacitor tubes: A proposal for a novel energy generation method.” Journal of Power Sources, 656, 1051-1068.

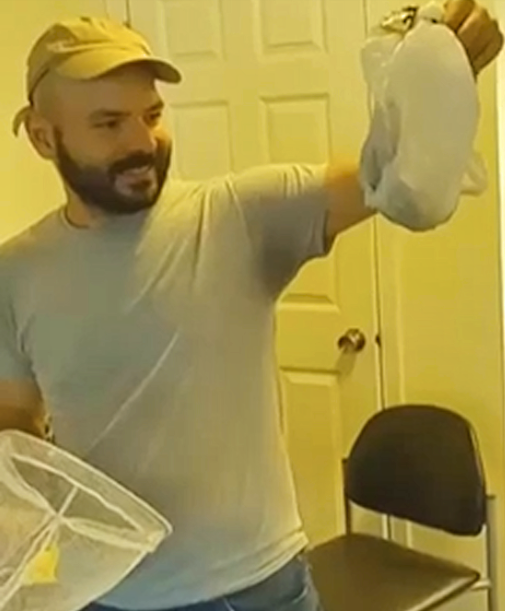

Mr. Colombo said he had a new bird, and a new mélo-kit, and did Marco want to come over and see it, he asked, as he beckoned his neighbor inside. Marco wasn’t really interested—he just wanted to crash on the sofa and open a beer and forget about the long day at work—but Mr. Colombo, like most people in Rome, never really took no as an answer; he only waved his hands more forcefully and herded him in, talking without pause about plumage and trills and transducers and accumulators, and Marco followed meekly.

The new bird turned out to be a parrot, of course, a small specimen with gorgeous colors. Its red head gave off a pinky hue on the glass tubes that connected the cage to the whirring machine. Marco was glad to see that the cage was big enough, way bigger than the one with the canary, which was shoved in a corner, its tubes already turning green. Both birds looked well cared for, their cages clean, their feeders full, and if the canary was quite still, almost comatose, the parrot seemed happy enough as it showered a deluge of insults on Marco when he approached the cage—not in reproach, though; it sounded almost like a welcome.

Mr. Colombo laughed. “She’s got the mouth of a sailor, that one,” he said. “But she means no ill.” Then he paused, puzzled. “Do you think curses have more generating force?” Marco knew the answer, he had worked out the experiments himself, but he also knew that Mr. Colombo wasn’t really asking for his opinion. He doubted the man even knew he worked at the university, let alone that he was involved in mélo-power research.

As Mr. Colombo droned on, Marco didn’t have the heart to tell him that lab results had shown parrots not to be very efficient at generating power. There had been a craze recently, everyone buying them after a congressman had mentioned in an interview that he had gotten one for his mélo-kit, but Marco had seen the data firsthand, and there was no scientific support for choosing parrots. Canaries, yes, of course. Blackbirds, maybe, or wrens, according to some research. A bioengineering team in France had collected promising data even on seagulls. But parrots—nothing special.

Mr. Colombo was pouring beer in one of the feeders. Then he turned around and tipped the bottle towards his guest: “Want one, too?” he asked. Marco accepted, glad to get on at least with that part of his evening, and he let his mind wander. He thought about Sara, who was probably coming home right now. He thought of how he would tell her about this meeting, mimicking the way Mr. Colombo waved his hands, just to make her laugh. He loved Sara’s laugh; it made his day brighter and was one of the things that had first attracted him to her. And then he thought about how he would tell her that the university had not approved his funding. Again. She would not laugh at that. Definitely not.

***

Blanchard, Y., Ricci, M., & Smith, M.-J. (2030). “Four calling birds: A comparative study on mélo-power generating potential in C. livia, T. merula, S. canaria and S. vulgaris.” Journal of Bioengineering Research, 12(4), 28-47.

Marco pressed a handkerchief to his nose as he passed under the cages and through the front door, but he still had to hold his breath against the stench. It was one of the many apartment buildings that had installed a full facade of bird cages—the super had pushed the idea as a surefire way of saving on costs, yes, ma’am, he’d said, it’s just a question of putting a few pairs of birds in there, he’d said, and we’ll have enough free power for the whole building, maybe even some in excess to sell. And at this price it’s a steal, ma’am! At the tenants’ meeting, Marco had tried to point out that the data didn’t support those plans, but it was useless. When you tell a Roman there’s savings to be had, that’s it, they’ll do anything. Marco’s own mother had voted in favor of the cages.

It didn’t work out as promised, of course; it couldn’t have. Wrens did not breed well in captivity, despite the super’s promises, so the number of birds did not grow. The mélo-tubes were also cheap ones, simple tin tubes running down the facade, so they didn’t pick up as much power as they could, and there was a lot of dissipation. Even so, the cages had cost a tidy sum. The owners weren’t ready to front any more money for additional cleaning, and the lady who came once a week to mop the stairs had refused to have anything to do with the cages, so the birds’ droppings had piled up higher and higher.

When the neighbors began to grumble—and that was soon enough, as the only thing that can make up for missed savings in the eye of a Roman is a chance to complain about it—the super proposed what Professor Sarti had already dubbed “the fool’s workaround”: let’s put lights in the cages, so the birds won’t sleep and they’ll only sing more! That’s not what had happened either, of course. The poor birds, exhausted, had died by the dozens, leaving behind only the empty cages and useless machinery. That’s when the super had done what many resorted to: he opened the cages and attracted pigeons in with some stale bread. Those pigeons were still there, cooing a low hum of power, and they were the source of the present stench.

When Marco’s mother opened the door to her flat, she peered over his shoulder, and disappointment flashed over her face before she smiled at him. Marco sighed inwardly and forced his lips to smile back. More than one year had passed since Sara had left him, and still every month his mother hoped to see her at the family lunch.

His forced grin turned into a real smile when he saw the small figure hurtling toward him from the sitting room.

“Uncle!” Teresa shouted, hugging him with all the strength of her five years. He twirled her around in the air, happy for her unconditional love, then walked over to shake her father’s hand and hug his sister briefly.

“So, what’s new among the birds?” Alfredo asked down his nose. He towered over Marco and the whole family and wasn’t shy about it, as he loved to rub in his good position and huge salary at some corporate bank.

“I’m getting a bird for Christmas,” Teresa piped up.

“Oh, yeah? What kind of bird do you want?”

“A bird that doesn’t sing.”

“Yeah, imagine that,” Alfredo cut in. “She could get any bird in the world, even a peacock, and the best mélo-K to go with it, and what does she ask for? ‘A bird that doesn’t sing,’” he said in a mock high-pitched voice. “What nonsense are you teaching your daughter, Claudia?”

Claudia shot him a glance that said she wasn’t going to get in the middle of it. That didn’t stop Alfredo.

“Don’t worry, though, I’ll make sure it’s a good investment, as always. I’m also looking into the new generation of tubes for my mélo-Ks.” He said mélo-kay, Marco noticed, as if the whole word was below a man of such importance as himself. “I’m thinking titanium—apparently it offers better insulation and less dissipation…” Marco let him talk, nodding every now and then, his mind elsewhere. He wasn’t going to offer him any assistance, nor any real information. Not that Alfredo was looking for either, of course.

After lunch, Marco went out on the balcony, where Claudia was smoking a cigarette. Their mother was lucky to have that balcony over the courtyard on the back of the building, away from the caged birds. Her next-door neighbor, Mrs. Forti, had all of her windows on the main facade, and she had had no choice but to seal them all off against the stench. She now lived with her front door always wide open to let in some fresher air from the stairwell, and had sued the apartment building for the right to install an air conditioner that would go through one of the other apartments and get air from the back.

“So, Mom tells me you are leaving.”

“Yes, next week. I will be back sometime in June.”

“Where are you going?”

“Around. There are plans for a comprehensive study on power potential in many bird species. Many colleagues all around the world are working hard at collecting data, but there’s still a lot to do. I’ll be around the Middle East over Christmas for a baseline on falcons, then Yves invited me to the Canaries to compare my data on starlings to the data they collected there in the wild. And the big work will be in the spring, trying to cover the migrations, but that will depend on what funding comes through.”

“And then? Will you get tenure?”

“Maybe.”

“Maybe? You are not getting any younger, you know. Isn’t it time to look for something else?”

“I love what I do, Claudia. The work is exciting, the field is huge at the moment, and there’s so much yet to discover.”

“Still the passionate dreamer, eh? But how are you holding on in the meanwhile? Isn’t the bursary running out soon?”

“In January, yes. But I have the travel funds for the next few months, and Professor Sarti said I can teach a class in the summer. I also have an agreement with a publisher: I’ll make recordings for them while traveling for a CD compilation of bird calls. They say it will sell like hot cakes. Oh, and if you hear of anyone who’d be interested in subletting my room while I’m away…”

Claudia looked at him, unconvinced.

“I never understood why you don’t get any money from the mélo-kits.”

“The patent is in the professor’s name, so…”

“But the idea was yours.”

“Yeah…But not the funds the university used to file.”

Claudia shot him another long glance, exhaling smoke slowly. She stubbed out the cigarette and made to go back inside.

“Claudia,” Marco called after her.

She stopped, but didn’t turn back.

“Don’t let Alfredo invest too much in the kits. They’re never going to yield enough.”

***

Fabbri, N., & Ricci, M. (2040). “No more silent springs: An urgent call to mitigate the long-ranging effects of mélo-tech on avian diversity.” Environmental Conservation Journal, 36(2), 159-166.

Half of the square was fenced off for construction work, so the many buses and all the people pouring out of the central station were crammed together in the other half, a maelstrom of bodies and trolleys, tourists and workers, sweat and shoves and pickpockets. The din reminded Marco of a time when he was a child: he was crossing this same square with his father, and he couldn’t hear his own voice, so loud was the racket; so he clung to his father’s big, calloused hand, and walked as fast as possible to get away from there. At the time, the noise came from the hordes of starlings who made the sparse trees their home.

With his room let out to a couple of tourists for the rest of the week, Marco was going to sleep in his office, but had a few hours to kill before he could even show up at the university. His backpack slung over his shoulder, he skirted the crowd and stopped to consider the construction site. There had been talks of this project for years now, politicians from both sides making big promises and proclamations, this will be a new start from our city, they said, the beginning of a new era, Rome will become once again the capital of the world, they proclaimed, and will lead the way into a greener future for the whole planet. Marco was curious to see how it was going.

They had removed all of the old bus shelters to build a canopy of perforated bricks, set in an array of two-meter-wide tubes. Marco knew everything about the technique: it was said to be the latest in mélo-tech, but that was eight years ago, when the project had first been proposed. It was supposedly the best solution with large avian populations, so it made sense back when Rome was full of songbirds.

That was not the case any more. Starlings had been stolen, pigeons had been lured away into private cages, parakeets had been starved to death. Fines were imposed on those who endangered the birds, but still Roman people found a way, in the unshakable belief that anything that belonged to the city was fair game, because it belonged to them personally. It was a massacre. Even seagulls had learned to steer clear of the city. The few birds left—a few dozen pigeons, some sparrows here and there—would never be able to generate the kind of power needed to justify such an infrastructure unless they were repopulated.

Now the construction site looked abandoned—Marco didn’t know whether for a strike, for lack of funds, or because they had found some ancient artifact that would stall everything for a few more years. A small family of pigeons had taken refuge between the bricks, cooing softly as they scanned the area for crumbs and fought over an old piece of sandwich. Something lodged in his throat that felt like guilt.

“At least they are alive.”

Marco turned around. He hadn’t noticed the woman who had stopped next to him. She was around his age, with dark hair and the same kind of worn-out jeans that he was used to wearing—but she held herself with such grace that she made them look almost fancy. She had a rainbow tote slung over her shoulder, and a pair of painted wood bangles clacked on her wrist whenever she moved.

“There’s so few of them left,” she said with a tiny smile. Marco nodded and smiled back. She handed him a yellow leaflet. “Birds need new protections. We’re holding a rally in front of the Parliament at four, if you want to come.”

Marco wasn’t sure whether it was her smile that swayed him, or the sad pigeons. “Gladly,” he said.

The woman beamed at him. “I’m Nina,” she said, offering up her hand. She had a flight of sparrows tattooed over her knuckles.

The rally, that afternoon, was a swirl of people: families with children waving stuffed parrots above their heads, young people with alternative hairstyles and smelling vaguely of joints, baggy-trousered trade unionists, people in suits and people in overalls, all worried, sad, seething, asking for a change. People took turns on the small stage, repeating appeals and sharing stories. Nina gave a heartfelt speech asking for national and international action to save the birds before it was too late. “We can’t all be like Venice,” she said.

Having just come down from there himself, Marco couldn’t agree more. Venice had become the prime example of how to bring together bird protection and power generation, with a solution that also fostered tourism and the city’s centuries-old glass blowing tradition. When art experts had first heard about the idea of installing a mélo-power engine in St. Mark’s Square, there had been an uproar. But it turned out to be a work of art: an ever-changing canopy of tiny, glass-blown tubes, each one hand-made and crystal clear; when they turned foggy from the pigeons’ cooing, the tubes were sold as souvenirs and replaced with new ones. The birds, once considered pests and almost eradicated from the city, were now pampered. Official signs encouraged tourists to feed them with approved seed packets sold by the city, and vets were hired to ensure the pigeons’ well-being, not to mention an army of sweepers that went out every night to clean after them. The whole system worked well enough to power the island’s street lights, but its delicate balance was impossible to duplicate elsewhere.

When Nina stepped down, she handed the microphone to Marco. He hadn’t expected to talk, but Nina looked at him encouragingly, so he did. And he didn’t plan what he said. It just happened.

“Hello. My name is Marco Ricci, and the birds’ catastrophe is my fault.” He looked around, but nobody had registered his name. Of course—it had never been his name on the patents, after all. So he continued: “I mean that literally. It was my idea, taking power from birdsong.”

And then, yes, silence fell on the square.

Afterwards, Marco couldn’t remember what he had said in that silence. He could remember Nina, looking at him fixedly, her face impenetrable. He could remember his burning need to explain how the dream for a greener future had turned into disaster. And he could remember the whole crowd listening, and the journalists, too. One thing he knew all along: he was kissing every last chance he had at university goodbye. He would have to look for another place for the night.

***

Ricci, M. (2045). “Brother mine.” The Big Issue Italy, 392, 12.

And then all the birds banded together, the girl said, and they elected a king to protect them. What’s a bird, asked the boy, her brother probably, not much more than a toddler.

Marco smiled, then pulled himself upright and packed the newspaper he was using as a pillow. The park bench was perfect for an afternoon nap in the sun, but when children came around after school, he knew he had to scamper. Better to start looking for a place to spend the night, anyway.

As he shuffled along the path—his rucksack clutched close under his arm, his hands pushed deep into his pockets to stave off the cold—he kept those kids’ words close to his heart, like a shining pearl. Children were still talking about birds, wondering about them, imagining a future where they could soar free again in the sky. There was still hope.

After the UN resolution that had banned mélo-kits and all mélo-power technology, Marco had expected to end up in jail. He deserved it, he thought, and wanted to atone for all the damage he had caused. But nobody ever came for him. So he kept doing whatever small things he could: he spoke at rallies, helped with charity events and fundraisers, kept watch over rescued chicks. He only earned a little money selling copies of The Big Issue Italy, but donated every cent he could. The recently approved EU funds would help the birds enormously; their numbers were growing already, thanks to the repopulation efforts—but even the best outcome could not wipe away his guilt.

He checked his rucksack pockets: he still had half of the sandwich he had scavenged that morning, that would do for today. He stopped at the fountain to drink—thank God water was still free in this city— and went on his way.

In front of the railway station, the huge mélo-tubes they had started to build all those years ago were still unfinished; long abandoned, they were teeming with weeds, and often rats. But they offered space enough to lie down comfortably, and good cover when it rained, or when the wind picked up, so they were the first place Marco checked. Somehow it felt right that he should sleep there, in the remains of the machine that he had almost destroyed the world with. He peeked inside one of the tubes and found it empty, save for a few crumpled sheets of newspaper—this was a lucky day.

He pushed the rucksack over the rim and hoisted himself. He grimaced when his shoulder protested against the weight, and let his body roll down the inside of the tube. Only when he reached the bottom did he notice the fluttering.

He froze. Months and years of field research had left him with that instinct, because birds were easily spooked. Five minutes later (or ten, or one hundred—Marco had been forced to sell his watch one year before) there was the fluttering, again. Slow like a glacier, holding his breath, he reached for the sheets of paper and moved them.

And there it was, that tiny, brown flutter. A sparrow, alive and free, here in this tube. It tilted its head to one side and gaped at Marco, as if to weigh him, then turned around and went back to its business, foraging for crumbs.

“Hello, little brother,” Marco whispered. And slowly, slowly, he took out his sandwich to leave more crumbs. In his mind he composed a poem, wondering if the magazine would ever publish it.

That night, as he fell asleep, a smile fluttered on his lips, like a hint of hope.

***

Brown leaf a-flutter.

I’m sorry that I’ve wronged you,

O little brother mine.

© 2025 by F.T. Berner

3496 words

F.T. Berner has always loved weaving words together in many languages, so she became a translator and then a writer. She lives in Italy with her husband and, sadly, no pets—so she listens to birdsong through her windows. You can find her online at ftberner.wordpress.com and @ftberner.bsky.social.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.