edited by Hal Y. Zhang

Content note (click for details)

Content note: Murder-suicide.I love Him from the instant I have eyes.

I can’t wrap my mind around the intentions of a god, but I do understand that He’s the one bringing me to life. His light brown skin, flecked with dust and paint and plaster, is the softest thing to ever make contact with my exterior. I stand scarcely a foot above Him, but His presence takes up the entire room—engulfs the world itself. He looks me over critically, irises the darkest of brown, and continues to chisel around the rough shape of my face.

My features have been sketched onto me with chalk. I’m too basic to behold Him, too crude. I would shrink away in shame if only I could move.

It’s the strangest thing. Some part of me is aware that I’m something different, that I’ve spent my existence so far as part of something bigger. I think, once, I belonged to a mountain, maybe even the face of a cliff. Something dug me out, ground me down until I was smooth. I was hoisted this way and that by hundreds of hands. I’m older than life itself; if I truly rack my memory, I can maybe pinpoint the exact age that humanity found its legs.

In all those eons, I haven’t experienced anything like this before—this awareness, and a sense of self. The emotions that go hand-in-hand with living, when I hadn’t known before that life was something worthwhile. Moreover, I haven’t encountered anyone like Him before. He looks at me with intention, with a vision, and I want to melt into something malleable in order to suit it.

I’ll do anything for Him. Be anything He wants me to be.

***

I don’t follow the passage of time by the light outside, though He seems to prefer to work when it’s streaming through the enormous windows of the studio. I don’t measure it in the subtle ticking of the timepiece situated above the doors, or gauge by the fluctuation of noises coming from outside—growling metal, blaring horns, the droning of conversation. I know the difference between night and day because He is the sun; He walks in, and everything brightens—the mosaics and murals, the blanketed easels and clay busts.

He doesn’t always work on me alone, but He does make it a point to chisel and sand sections of my form away at least once per visit. I try to be understanding. He can’t devote all His time to one thing—it’s clearly not in His nature. Where I am immovable, He is mercurial.

Today, He flits between two canvases, letting a thin base coat dry while layering details on another. I’m fascinated by His hands, especially. Slim fingers wield a paintbrush like a feather, handle it like a sword. With every stroke, beauty gushes forth. The colors He chooses are purposeful and vibrant. The placement of the paint is so careful, yet looks effortless.

I watch for hours, and only break in my admiration to reluctantly urge Him, Eat. You can’t go on for much longer without eating something.

He puts the paintbrush down. I brim with affection.

Eating is a strange thing, but I’ve come to realize it’s something He requires to keep on. It’s an unappealing prospect to have to fill oneself repeatedly, but He makes it look like a transcendent experience each time. He sits on the floor by the window, curls spilling over His forehead as He tilts forward over a plain bag.

He devours the contents. I watch the slow drip of a tangerine’s juices slide down His fingers. If I had a mouth, I could part my lips and coax His hands towards them, swallow each finger one at a time to the knuckle and clean them with my tongue.

I have never tasted before. I imagine nothing is more exquisite than the flavor and texture of Him.

He exhales, opens a bottle of water. His throat bobs as He drinks, head back and eyes closed, an expression of ecstasy if I ever saw one. I want to put that look on His face. I want to be the reason He smiles.

The wonderful thing is, He does smile at me. When He’s particularly satisfied with the shape I’m taking, He beams wide, proud. His teeth gleam like polished marble. His lips frame them in kissable perfection.

I ache, but I wouldn’t trade those smiles for anything. His happiness means more to me than my own selfish urge to touch Him, hold Him.

But I can’t help but wonder if there’s a way we could have both.

***

He focuses on my body for some time. He whittles away at rock with instruments both powerful and dainty, drilling right through stone and sending bits of rock scattering at high speeds, then refining pieces to ensure He doesn’t lose too much structure.

I’m taking the form of a human. Because that’s what He is, ‘human’ is precisely how I want to look.

What I want to be.

It takes days for Him to fashion legs, though they’re still blocky. My arms are up, framing my head, showing off what will be my torso. I don’t know what He plans to do with my hands, if I’m to have any.

I hope He’ll give me hands, so that I might one day interlock my fingers with His, draw Him near. He rests His own fingertips against me on occasion, and I swear I can feel His heartbeat all the way through them. A fluttery hot pulse.

I also decide, then, that I want Him to give me one of those. Carve me a heart. Make me one, so that I may give it to you.

He’s distracted in the days that follow, sitting at a potter’s wheel to form an odd shape, bumps deliberately formed over the curves. In the end, He winds up demolishing each one, returning them to formless clay. He seems dissatisfied with the shapes, frowning more often than not.

So I dismiss my want. I don’t need a heart. What I need is for Him to smile at me while He sands and grinds me down, to have His focus, to please Him.

He abandons the potter’s wheel and resumes His work on me.

***

It isn’t until my face truly begins to take shape that I realize every portrait, every bust He has created—they’re all of me. The long nose, the waves of my hair, the deep-set eyes. The thrill I get when it dawns on me is incomparable, like lightning striking a tree only to leave blooms behind.

It can only mean one thing. He loves me. He feels the same way.

With all the tenderness my stone gaze can muster, I watch Him work. He’s finished with my head and is working on my arms, smoothing the joint of my elbows, emphasizing the soft bulge of muscles. His face is so close to mine.

Would He kiss me, like this? Surely He wants to. If He’s been painting me all this time, He must have been longing for this before He even began sculpting.

Kiss me.

He pauses, draws back. His eyes flicker over my face with obvious emotion, but I can’t read what it is. His gaze lands on my mouth.

Please, kiss me.

Gently, He glides the sandpaper under my lower lip, just once. Then He shakes His head as though to clear it, going back to work on my biceps.

That’s okay. Perhaps He wants to wait until I’m complete. It will mean more, then—a celebration. I can wait.

***

He’s the only person to have ever come into the studio before. That’s why it’s such an unwelcome surprise to see Another Man walk in one morning, hand in hand with Him.

The Other Man flicks on the light, looking around the studio with a smile playing on his lips. “Obsessed much?”

He laughs. I’ve never heard Him do that before, and nothing could possibly compare to its chime.

“So where do you want me?” The Other Man wanders, idly inspecting all of His works of art with a soppy grin. Hot loathing pipes through my entire form, the resulting surge of strength useless to me without the means to move. While the Other Man drinks in one of the clay busts, He sets down His bag, draws open the blinds.

“Pull up a chair wherever you want,” He answers. “Clothes off.”

“Already? You aren’t going to woo me first?”

He laughs again. “Paying for breakfast was the wooing. You should probably be close to the statue, but not too close. I want to be able to see you, but…”

“Avoid any flying debris?”

“Yes, that.”

The Other Man strips his shirt off, mussing his wavy hair. He drags over a folded chair, but stops on his way past me, deep-set eyes sizing me up.

“Wild,” he murmurs. “It’s already so lifelike.”

“It’s basically blocks from the waist down,” He points out.

“I mean aside from that.” The Other Man quiets a moment. “I can’t believe this is how you see me.”

“David…” He abandons the sculpting tools He was preparing, going instead to the Other Man, arms winding around the Man from behind. “You’re the most beautiful man I’ve ever seen.”

The Other Man closes his eyes briefly, tilting his head back. “The most beautiful man with a block for a dick.”

He snorts in surprise, then buries His face in the crook of the Other Man’s neck, muffling chuckles. I want to tear the Other Man’s head right off his shoulders, frantic hurt swirling through my head like storm clouds.

“If you want your dick to be accurate, then you’ll need to take these off,” He murmurs, hands roving down to the fly of the Other Man’s jeans.

Stop it. Don’t touch him. Touch me, instead.

He lingers over the button. For a second, I think He’s heeding me.

But He ignores me, ultimately, and I can do nothing but stew in rage, watching the Other Man take everything I’ve ever wanted.

***

I stop seeing myself in the colors and curves He puts on paper. Their shapes—my shape—offends and baffles me now that I know what I am. I only exist to bear the Other Man’s likeness.

What I don’t understand is why.

The Other Man must be inadequate in some way. There’s something about him that He wants to change, perhaps, something built into the Other Man’s physicality. I beg for this to be the answer. I pray, because if He is building me to be a better version of His lover, then taking the Other Man’s place is inevitable.

Yet, if this is true, why do His canvasses not serve my purpose already? Why does He look so softly upon every depiction, like we’re all equal? Equal to each other, but so far beneath the Other Man?

Choose me, I implore Him day after day. If you can’t do that, at least give me a reason why not. Why it can’t be me.

What am I for, if not for you?

He scratches imperfect flecks of rock away from my legs, and doesn’t deign to answer.

***

The ache of betrayal, of loss, doesn’t get any easier to bear with time. He continues to work on my lower section, spending hours on each individual toe, but I can hardly stand His touch when I know it’s not exclusively mine. Every spark I experience from His hands is stolen, a dirty secret. He allows the Other Man to come into the studio every night as He finishes His work, kisses him, laughs with him. What worth I try to invent for myself is gracelessly smashed with every smile the two of them share.

I stop keeping track of when He’s here and when He’s not. It all feels equally lonely. I just know that eventually, He stops His work and takes several steps back, dragging a sleeve across His forehead and staring up at me in abject wonder.

“Finished,” He whispers.

I don’t feel any different. I don’t feel whole. But He says He’s finished with me.

I try to convince myself it’s for the best. I’ll exist forevermore, knowing He loves the shape of me, if nothing else. Maybe there’s contentment to be found in that.

But no… The more I attempt to believe it, the weaker my justification becomes. I’ll be tormented until the end of time, wondering why He would create something only to spurn its affections, wishing I had it in my power to enchant Him as He did me.

Or any power, at all.

Kiss me. Just once, I implore Him. Just to know what it’s like.

Slowly, He draws near again. I stand nearly a foot taller than Him, so to cup my face, He reaches up high. His head tilts back to look me over.

He does not kiss me. Instead, He runs His thumb across my lips.

“I can’t wait for him to see you finished,” He murmurs.

He closes up the studio. If I could cry, I would.

***

The next time He returns, it’s with the Other Man again. He’s vibrating with excitement, almost pulling in the Other Man by his hands but frequently letting go to fuss with His hair, his shirt.

“I haven’t seen you this nervous since you proposed,” the Other Man notes dryly, but it’s affectionate. Light. There’s tied cloth over his eyes.

Hatred renews itself like it’d been merely reduced to embers, and the Other Man’s breathed it back to a blaze.

“I just…I hope you’ll like it,” He says sheepishly. “I’m going to put you where I want you and then get the lights, okay? Don’t peek.”

“I won’t.”

“Swear it. Swear on your mother’s life you won’t peek.”

“I refuse. I love my mom and I won’t take that chance.”

He steers the Other Man over. “But you already promised you won’t peek! That should be nothing!”

“What if I can’t resist temptation like I think I can? Not risking it.”

He drops a kiss on the Other Man’s cheek. I stare down at the Other Man and wish nothing but pain and death upon him.

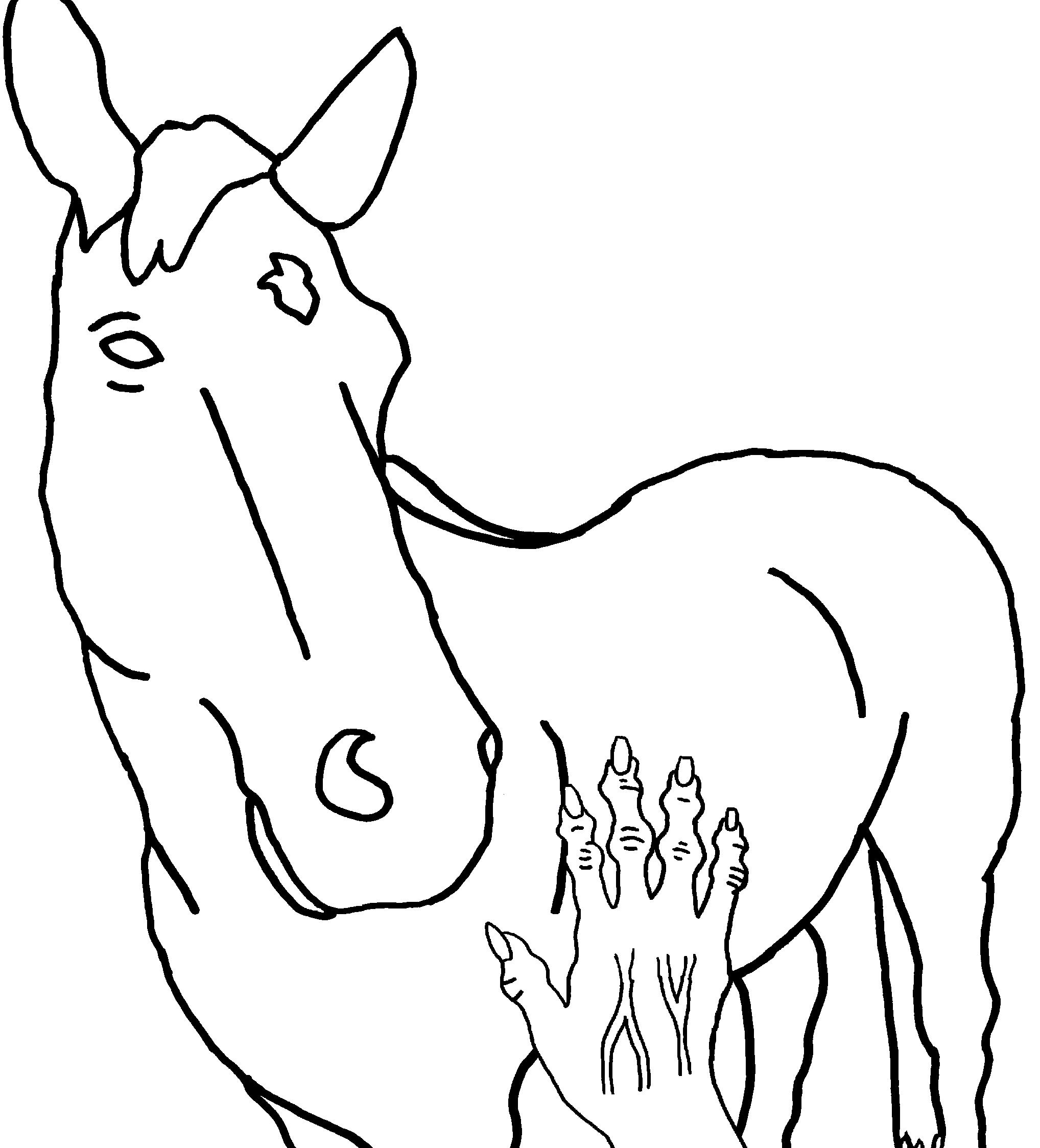

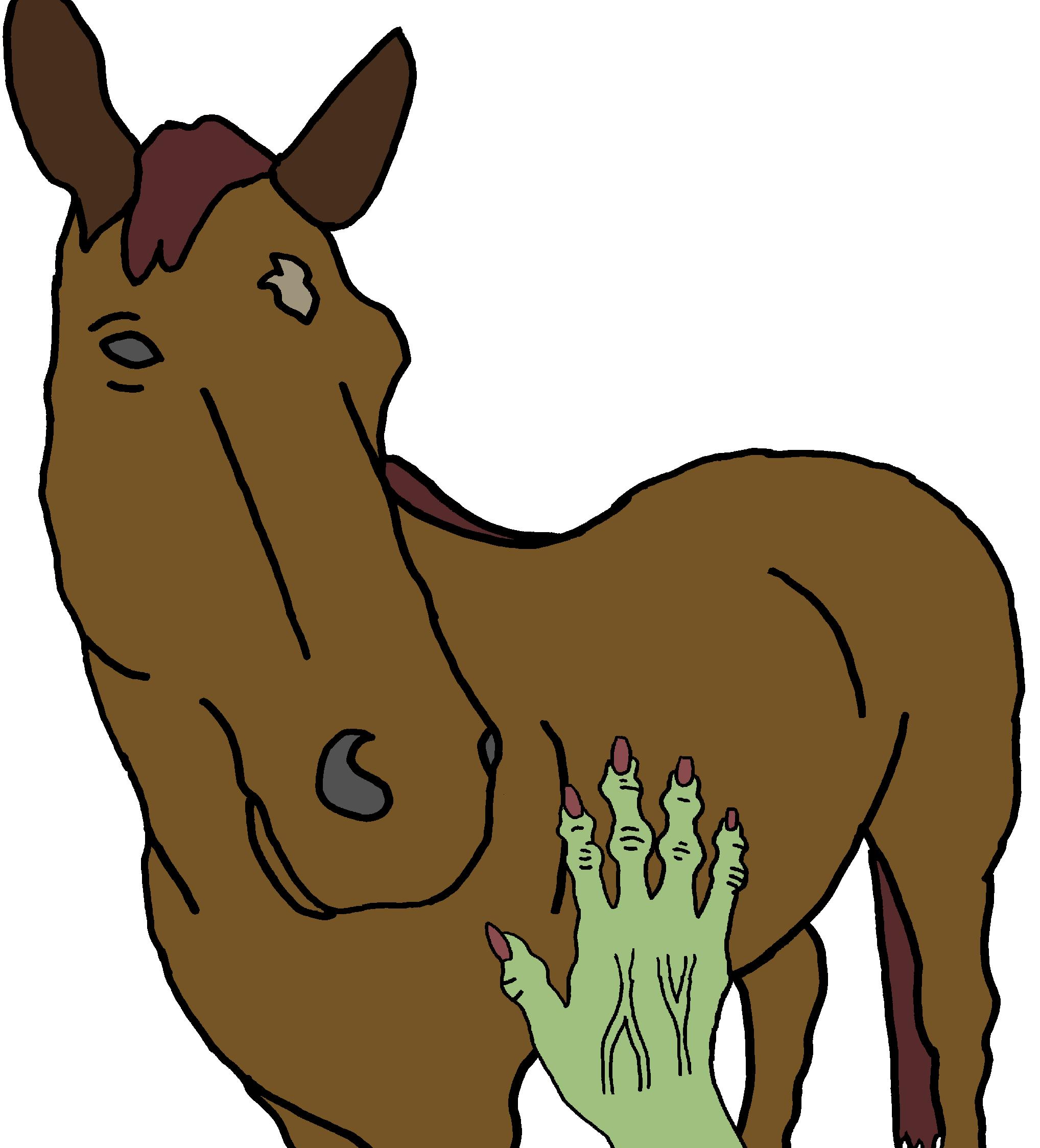

If only I could step down from the pedestal I’ve been carved into, explain to Him how much more I adore Him than the Other Man ever could—

He flits over to the windows to draw the blinds.

With one final burst of emotion, I surge forward.

When I topple, it’s straight onto the Other Man, crushing him beneath my might and mass. My body cracks on impact, but it’s nothing compared to the crunch of bone and splatter of the Other Man’s blood. It pours from his head out across the floor like watered-down paint.

My final satisfied thought is that His scream eclipses any love He ever felt for His David.

© 2025 by R. Haven

2480 words

R. Haven hails from Toronto, Canada. His short stories have been published by Canthius, Soitera Press, and TL;DR Press, among others. Last Stanza Poetry Journal and Old Moon Press have published his poetry. He also signed a contract with Renaissance Press for a standalone horror novel and is represented by Kaitlyn Katsoupis of Belcastro Literary Agency. His website is theirritablequeer.com.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.