Content note (click for details)

Content note: Indirect Reference to Death, Mass Violence, Collective Punishment, ImprisonmentAli never got used to the things they asked for. All those mismatched items left behind in those desperate moments. But there would be only one item per family so he advised them to choose wisely.

Usually, it was something small. Grandmother’s favorite azure prayer beads strung on a nail on the high shelf reserved for religious texts, a lost doll the kids had just rediscovered or a lucky tie for those rarest of job interviews. Sometimes it became fiercely practical, like heart medicine, the keys to an old car that had miraculously eluded being pummeled by those angry whistling bombs or useless saving certificates and property deeds.

In the beginning, he had used his gift as a child does. To try to wrong the little rights. To copy the answers of the smartest girl in class (beautiful flowy handwriting) or knowing just when to intercept sweaty Ahmed’s long pass and score the winning goal for his beleaguered football team.

But he could keep on cheating till eternity and nothing would change as long as the Occupation Housing Authority (OHA) controlled the territory. He would never get a job because there were none for anybody below the age of 40, no marriage before 50 or jumping the endless queue to the overcrowded beach that opened once a month on a random Friday. Instead, he had to wait as everyone else did in the Zone.

The Zone, casbah of the damned, the darkness of its pitted alleyways punctuated by nightflares. But it was the only world Ali had ever known and it was getting smaller every year or so, whittled away by the regular mini-invasions to root out the “miscreants”’ amongst them, houses demolished for archaeological/religious significance, OHA administrator rights, etc.

Ali’s vocation emerged out of the mad contours of life in the Zone provided he was close enough in the first place. Every so often, a roof knocker bomb would politely announce the randomized destruction of a designated apartment tower and let off red-hearted smoke, a warning for everyone in the Zone to behave.

Soon the evacuees of the destroyed building would start piling up around him with their requests and Ali would have to go to work. With desperate smiles, they would plead for him to go back (literally and temporally) to save the precious belongings they had abandoned in the terror of their flight.

Those ten precious, splendid minutes were all Ali ever had for his neighbors. It was the farthest extent he could stretch his being backwards in time before the doomed building was levelled by the damn OHA. By horrible synchronicity, this period aligned perfectly with the gap between the OHA’s warning and bombing.

All Ali asked for was they pay him something, anything they could spare from lives that had just tumbled into a pile of rubble. It all went to his parents, every last dinar. For a long time, he wondered if this hopping through time in this narrowest of spaces was his deepest destiny. As if he had been picked by fate expressly for this doomed place.

The smoke and dust seemed endless the day Burraq Heights was bombed for the third time by the OHA. Each time the Burraq’s stubborn owner had rebuilt his apartment block a storey lower hoping and praying to escape scrutiny.

Ali had lurched into the condemned building, managed all he could. His old Red Crescent canvas bag and repurposed combat vest bulged to the brim with lost and found. There was only one failed recovery, a silver ring rubbed against a saint’s shrine for luck. Exhaling slowly, he happily ran a hand through his scant hair, feeling relatively fresh and counting his money. It was a good day for recovery.

All this time, the loudspeakers emblazoned with the sleek logo of the OHA reminding them the good things in their lives:

1. Security (The lowest crime rate in years! So many criminals rounded up, gone without a trace.)

2. Well-settled refugees (Generation 6? Who was counting anymore?)

3. Environment-friendly roads made from plastic waste (Potholes a convenient size for a child to curl up and sleep inside.)

4. Graceful apartment towers lined with bright red cladding (those highly flammable borders lit up like a Roman candle when the bombs hit.)

The sun-drenched boulevard was so bright that he only saw the scrawny man when he was nearly on top of him. “You, lionheart, may all my generations bless you. Abu Zaman, please help me. My mother!” He was pointing in the distance, frame wracked by sobbing.

Abu Zaman, divine shadow, the snake which eats its own tail. They have a lot of titles for him. The dripping effusiveness of the prayers suggested he had no payment to offer. Ali tried to appear noncommittal. “Where in the Burraq, what was left behind? There’s nothing I can do about that now. It’s too late.”

The man’s seamed face strained as his finger pointed. Ali imagined his body toppling over into a hill of dust. “No, not in the Burraq,” he moaned, “she’s inside…our house.” Ali finally perceived the small pile of rocks, cragged like a cairn.

The Occupation had done a double tap, the man’s house bombed with only the slightest of time gaps with the Burraq. It was a rarity but who could divine the logic behind the biopolitical policies of the OHA?

The South Wind slashed Ali’s face with grit. He attuned himself, face like ageless stone. “Time of impact?” He said sharply.

“Four minute, two minutes ago,” the dazed son replied.

Not good. Barely enough. He would have three minutes with any margin at most.

He brought out his battered Zippo lighter in a flash and thumbed it sharply. He held his talisman aloft against fate, a passport to the dark void and leaned into his backward step. A blinking light steadied. And suddenly he was there and running past the rusty-railed veranda of the simple stone house.

He had been expecting a comatose woman, barely responsive. Instead, there was a mess inside. The barefooted little woman, wailing and weeping, had her wizened back to him. He called to her lightly and she wheeled around like an angry cat, her crystal eyes flashing out at him from under her turquoise shawl. He knew her from his childhood before his time travel had left a scar in place of every memory, each face a blur. Her name eluded him. She used to set out precious water for birds, always smiling at children and giving them creamy treats when they broke their life’s first fast in Ramadan.

But she seemed feral now, insensitive to all but the tide of blood and rage welling inside her. “My key, where is it? My son, my damned son, has hidden it. I’m sure of it.”

She moaned gently, “I couldn’t stop looking. He wants me to forget, curse him,” before she abruptly fell silent.

Patient Ali had waited for her to finish, didn’t doubt that she came from a long noble line and held fast to the rope like a desperate man groping in the dark. “Sayidaa,” he coaxed.

“Your son has sent me. Your face… It glows with the light of your lineage – surely you will sit on God’s right hand. Please come with me. The bomb is about to fall, I have seen it with my own eye.”

“So what?” she snapped, “We are all living on borrowed time, you most of all.” She stood still, her weathered upper lip curling stubbornly as she started her search again. Her densely veined hands shook slightly, knobbled by arthritis that the OHA didn’t permit to be treated. She was clawing at phantoms when he was trying to save her from annihilation. He hated her, this moth dancing around the flame. He felt exasperated and shouted. “Why can’t we just leave it? There’s nothing anymore. We lost.”

She was unfazed and flared at him. “So we will always be the wretched of the earth, always apologetic for our existence? Doesn’t our nation have a place under the sun? You should know better, Abu Zaman, you help so many.” Her voice rolled over him, a lullaby for resistance and revolt. “Son, we can still fight against the dark if we keep our heart and faith.”

He tried to tell her. The nation was dead. A thousand cuts, indignities, lies, and denials later, the Zone was all that remained. The vulture’s leavings. How does faith fare the sword? Fight how?

Her voice fell to the reedy whisper of a conspirator, “Can’t you just keep jumping? Ten minutes, again and again? Go back to when it all started and stop them in the very beginning. You could save our homeland.”

He wanted to laugh at the delusional hag. That wasn’t how it worked, how could it? He could barely manage the two jumps, one after the other, he had just made and now she wanted Ali stretched into infinity, sliced into tiny fragments.

He sucked in air, his chest red and heaving. Even his breathing sounded weak and strange to him. Within him the space between things moved, a subtle shift of infinite dimensions. An expanse was emerging that had never existed before.

For Ali who lived ten minutes at a time, tasted the presence of what had once been. He saw the lady’s lost home. His eye the spy of his heart. And he couldn’t avert his gaze. The glowing house standing on a windy hillock. The cool shade of date palms, the earthy smell of lively flowerbeds, trickling fountains playing the music of heaven, enormous teakwood doors, marbled staircases and most clear of all, the library which glimmered of books filled with endless dreams.

This loss was a reality Ali thought he accepted. Like everybody else in the Zone, his family had lost their dream as well. He saw the blank faces and empty eyes of his mother and father who lived in a squalid apartment that had miraculously never, not once, been hit. He knew why they rarely left its narrow confines. It wasn’t for any fear but the singular fact that the world outside, this Zone, held nothing of value for them. They had so few words left now, so desiccated were their empty lives. At night, he would fall to his knees and press his forehead hard against a gifted prayer mat, pleading and sobbing. All his efforts a band-aid for a gaping wound where bone gleamed back.

Deprived of land, hearth, factory and shop. All lost to the relentless tide of an invasion that now curled up into the black night of the OHA. But would they be deprived of memory, of thought, as well? No matter how painful, perhaps this was the only way for their brutalized humanity to survive…

“Do you think it’s possible to take all these broken pieces and make something new out of it?” he asked no one in particular.

Lost, he couldn’t remember the bomb streaking towards his destiny. It might as well have been the mother of all bombs that had pockmarked the Zone over the ravaged decades. He recalled the dusty words of a poet whose name was lost to ashes. The answers we hunger for already reside in our heart. He saw himself, a proud man standing tall in the redness of dawn.

So Ali fell to his knees to look below the tattered sofa that served as her humble bed. He tossed open the roughly finished cupboards, the low humble shelves. Spice jars and mirrors fell, dashed against the dirt floor.

He screamed and raged for that key. It would be found for the lady, for himself, for their weeping nation, he vowed. The old woman smiled at him faintly, like a ghost. Her dry lips moved silently in prayer before she blew her blessings upon him. It felt like a cool breeze for his tired soul, all the way from a homeland he might still know.

© 2022 by Murtaza Mohsin

2000 words

Murtaza Mohsin takes things as they are and tinkers with words. He lives in Lahore, Pakistan and is curious to see where this writing thing goes. His fiction has appeared in Future SF Digest and is forthcoming in Galaxy’s Edge.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

Davian Aw’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Daily Science Fiction, Stone Telling, LampLight and Star*Line. He also wrote roughly 240,000 words of Back to the Future fan fiction as a teenager and has never been that prolific since. Davian is a double alumni of the Creative Arts Programme for selected young writers in Singapore, where he currently lives with his family and a bunch of small plants.

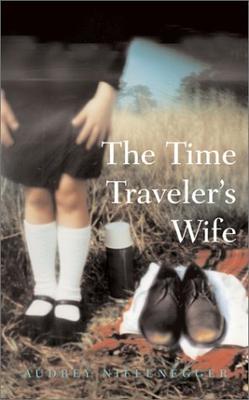

Davian Aw’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Daily Science Fiction, Stone Telling, LampLight and Star*Line. He also wrote roughly 240,000 words of Back to the Future fan fiction as a teenager and has never been that prolific since. Davian is a double alumni of the Creative Arts Programme for selected young writers in Singapore, where he currently lives with his family and a bunch of small plants. My wife and I took my mom to The Time Traveler’s Wife, a convoluted SF romance starring Eric Bana and Rachel McAdams. The movie is based on the book by the same name, written by Audrey Niffenegger. I haven’t read the book yet, but it’s on my must-read list. In the movie, Bana plays Henry, a man with an extremely rare genetic disorder which causes him to time travel both forward and backward. He has no control over when and where he goes. McAdams plays Clare, the title character who becomes his wife. Their relationship is… complicated. He meets her for the first time when he’s 20-something, and she’s in college. She meets him for the first time when he’s 40-something and she’s five years old. Like any relationship, they have good times and bad times, but unlike other relationships, the good times for one person often coincide with bad times for the other person.

My wife and I took my mom to The Time Traveler’s Wife, a convoluted SF romance starring Eric Bana and Rachel McAdams. The movie is based on the book by the same name, written by Audrey Niffenegger. I haven’t read the book yet, but it’s on my must-read list. In the movie, Bana plays Henry, a man with an extremely rare genetic disorder which causes him to time travel both forward and backward. He has no control over when and where he goes. McAdams plays Clare, the title character who becomes his wife. Their relationship is… complicated. He meets her for the first time when he’s 20-something, and she’s in college. She meets him for the first time when he’s 40-something and she’s five years old. Like any relationship, they have good times and bad times, but unlike other relationships, the good times for one person often coincide with bad times for the other person.