written by David Steffen (and no one else, alas)

INTRODUCTION

Since time immemorial, one of the perennial topics of humankind has been to compare music. Whether pop is better than country, whether this band is better than that band, or this song better than that song. Before the invention of writing, one can imagine heated arguments about who was the best drummer.

(ANGELICA, if you’re reading this, I’m sorry. For everything. But most of all I’m especially sorry for taking what we had for granted. Don’t worry, the parts that are bold-and-italicized are only visible to you, keyed off of your IP address. I can only hope that even though you’ve changed your number and email address that you might have left this one thing unchanged. I know you would be mortified if this were public, and wouldn’t hear the end of it from Maurice. I wouldn’t do that to you!)

Arguments are powerful things. Relationships have formed and relationships have ended over this subject matter (because some of us become complete assholes on the topic and don’t think about other people), and we believe that many relationships can be saved if we can apply some elements of scientific rigor. The subject matter as it has been historically framed is inherently too subjective and therefore is a breeding ground for disputes and hard feelings. Even scientists, we who pride ourselves on being able to set aside our emotions and think rationally, have been known to make this mistake, though we of all people should know better.

We posit that our mistake has been rushing into the discussion without agreeing upon criteria (and also about using absolute statements in combination with invectives, statements like “Anyone who likes 98 Degrees more than The Four Seasons is a complete @*&@#$ @#*@! have no place in a laboratory”. I was not lying, but I should have considered your feelings. I didn’t know how hard you would take that until you replied to say that One Direction was better than Third Eye Blind. That still stings.), and so have entered the debate in bad faith with the conclusion in mind ahead of the evidence. We considered what criteria might be used for the judging of musical bands. As with the objective comparison of so many other types of subject matter, we have come to the conclusion that the answer lies in mathematics. When we sent Voyager to journey beyond our solar system, we wrote our message to the universe in the languages of music and mathematics. If it’s good enough for aliens, it’s good enough for resolving disputes with our fellow music-loving humans. (I would send you a gold record!)

PROPOSAL

Therefore, I propose The Horowitz Method (I hope you’re not upset that I named it after you. I know it’s traditional for the founder/inventor of a scientific method or discovery to be its namesake, and while you didn’t propose the method nor write this article to propose it to the public, I wanted to acknowledge the role that you played in its instantiation. You are the best research partner that I’ve ever had, so rigorous and well-spoken and hilarious when you want to be, and while yes I have at times been jealous of your success, that success was earned and anyone is lucky to work with you. I also admit that another factor in choosing your name was that I hoped you would hear about the proposed method via mutual colleagues and would be curious enough to visit this page where you could read these messages. If you’re upset about the naming, I promise I am willing to change it), an objective method of rank-ordering musical groups in a metric-based approach that is thus subject to peer review.

But what mathematical measure? If we were talking about comparing one song with another, it might be easier, for the music itself is inherently mathematical–meter, tempo, time, number of notes, pitches. But a single musical group could have any number of songs, and the number could grow every day–what particular songs would one use to judge a group? Their newest? The whole body of their work? And some bands release songs so regularly that any conclusion drawn would have to be re-examined very frequently. And that’s not even to speak about what particular measure to use which, we know from personal experience, becomes a dispute of its own.

No, if we are going to compare musical groups and expect a somewhat stable outcome, we must not compare their songs, we must compare traits of the group themselves. The genre? The style? Again, too subjective, one could argue that a group is one or another or maybe both or something entirely new. We need to focus in on something entirely indisputable.

The band name. (Please hear me out and look at the data. And I look forward to seeing your refutation in a prestigious journal instead of publishing it on your own site)

And, in order to apply mathematical rigor to it, the dataset we will work with will be band names with numbers in them. (yeah, I know, but I figured we had to start somewhere)

“My favorite musical group doesn’t have a number in it,” (Black-Eyed Peas) some of you are declaring at this very moment (Faust, Lionel Richie, Adele). Then take heart in knowing that your favorite band is incomparable, in the mathematical sense. If you want to compare your group with others, I’m afraid you’re out of luck, at least for the time being. You may as well try compare (8/0) to (10/0), or compare a walrus to a the clock speed of Pentium processor, or a raven to a writing desk, the question inherently has no meaning, and if you don’t like the system, propose an alternative. (I dare you. You know you want to!)

By using a mathematical system, we can define and rank and draw some mathematical conclusions about the dataset. This system doesn’t define which band is the “best” because that is an inherently subjective concept, but it does define which is the GREATEST, mathematically speaking. (That’s right, that’s how sorry I am, I am resorting to PUNS . In PUBLIC. May the Flying Spaghetti Monster forgive me. )

CORNER CASES

Even in something so simple as numerical ordering, there were some corner cases that are worth noting, especially when other researchers consider peer review.

Only groups that had a number clearly as part of the name were included in the dataset. Groups that clearly had numerical etymology but did not contain what we would recognize as the word we commonly use for the number were not included. This excluded, for instance, Pentatonix, which was a corner case in itself, but if we included root words then we felt it would have to include any other names that include root words, which might not always be easy to determine in every word that it may not be common knowledge that they are numerically based, such as “quarantine”.

But a number may be part of a larger word and still be included as long as the number itself is clearly visible and appears to clearly refer to the number. So, Sixpence None the Richer was included as the number 6 and Oneohtrix Point Never was included as the number 1, but Bone Thugs and Harmony was not included because “Bone” clearly is not meant to refer to the number “one” even though it contains the letter sequence.

At first, ordinal were included, like Third Eye Blind, as its integer number (in this case, 3). But, after considering the earlier decisions about not allowing words with number etymology in them, this seemed inconsistent with that. In an attempt at greater consistency, these were still included in the dataset, but as fractions whenever the word was correct–so Third Eye Blind was included as 1/3 rather than as 3. We expect that this will be a point of contention in peer review and we welcome the debate. (Note that I didn’t do this just so that One Direction would be greater than Third Eye Blind, and how dare you suggest I would undermine my own scientific integrity)

Roman numerals were included, but only when the numeral clearly referred to a number. So, King’s X was excluded even though the X might be considered a 10, because that doesn’t appear to be how it’s used. But Boyz II Men was included, because it is spoken as the number representation, rather than being pronounced “Boyz Eye Eye Men”.

Musical groups with more than one number in their name, like The 5,6,7,8’s, or Seven Mary Three, were treated as a dataset, included once for each number. This means that Seven Mary Three is both greater than and less than The Four Tops.

STATISTICAL RESULTS

Many of the results of this dataset are illustrative of the problems inherent in trying to summarize a dataset with extreme outliers. At the same time, the usual methods for excluding outliers seemed inappropriate for this particular application, because if we are to determine which band is greater than another, but exclude the greatest bands in the dataset, this would undermine. Note that, among other things, this means that the GREATEST band is also the ONLY band that’s above average.

The Greatest (Maximum): Six Billion Monkeys

The Least (Minimum): Minus Five

Average: 28,846,316.88

Standard Deviation: 416,025,135.8

Median: 5 (see data list below to see the bands with value 5)

Mode: 3

Again, note how the average and standard deviation in particular were skewed very high by the high outliers in the dataset, particularly the number of 6,000,000,000, when the majority of the rest of the numbers were less than 100.

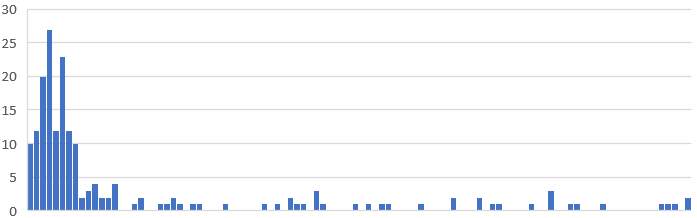

HISTOGRAM

While the dataset as a whole is very spread out to make a displayable histogram, since 90% of the datapoints are between the values of 0 and 100, that a histogram of the data within this range could be interesting.

FURTHER STUDY

If this measure were widely adopted, it is possible that it would have the consequence of encouraging musical groups to be more likely to pick names with numbers in them, or to add numbers to existing names. We see this as a positive result in itself, though it could make future results require more peer reviews as bands try to pick the greatest number to improve their placement, which may bias the data.

Although we explicitly avoided ranking individual songs here, the same method has potential for that as well as albums or movie titles or books (i.e. 1984 is greater than Slaughterhouse Five) or really anything else that has titles that might include numbers in them.

(And the most important under the topic of further study is whether you will see this as the olive branch it is meant to be. My research is lesser without you, and I hope you feel the same way about me. You know how to reach me, and I hope you do contact me. Most of all, and you know that I’m not good at the touchy-feely stuff, is that I miss you as a person. You are an incredible human being.)

THE DATA

Here is a list of the complete set of datapoints used in this study. While this is meant to be as complete a list as possible, it is recognized that this is likely not a comprehensive list, as with the Internet publishing where it is it can be hard to define whether a band is a band or not–i.e. what if there is a musical YouTube channel with a numerical username, or what if someone self-publishes a CD on their own website that no one has heard of. Further studies can propose methods of defining what exact musical groups should be included and which ones should not.

| Six Billion Monkeys |

| 10,000 Maniacs |

| Powerman 5000 (Yeah, I know, but numbers don’t lie) |

| Andre 3000 |

| B2K |

| Death From Above 1979 |

| The 1975 |

| 1349 |

| 1000 Homo DJs |

| 999 |

| MC 900 Foot Jesus |

| 702 |

| Galaxie 500 |

| Appollo 440 |

| 311 |

| Front 242 |

| Blink 182 |

| 112 |

| Zuco 103 |

| The 101ers |

| 100 Flowers |

| Haircut One Hundred |

| Ho99o9 |

| 98 Degrees |

| Old 97’s |

| Revenge 88 |

| Combat 84 |

| M83 |

| Link 80 |

| EA80 |

| Seun Kuti & Fela’s Egypt 80 |

| Resistance 77 |

| JJ72 |

| SR-71 |

| 69 Eyes |

| Sham 69 |

| 65daysofstatic |

| Eiffel 65 |

| The Dead 60s |

| Ol ’55 |

| 2:54 |

| The B-52’s |

| 50 Cent |

| 45 Grave |

| Loaded 44 |

| *44 |

| June of 44 |

| Level 42 |

| Sum 41 |

| UB40 |

| E-40 |

| 38 |

| 36 Crazyfists |

| Thirty Seconds To Mars |

| Apartment 26 |

| Section 25 |

| 23 Skidoo |

| 22-Pistepirkko |

| Catch 22 |

| Twenty One Pilots |

| Matchbox Twenty |

| East 17 |

| Heaven 17 |

| 16 Horsepower |

| 13 & God |

| Thirteen Senses |

| 13 Enginers |

| Thirteen Senses |

| d12 |

| 12 Stones |

| Finger Eleven |

| T-11 |

| Ten Seconds Over Tokyo |

| Ten Years After |

| 10cc |

| 10 Years |

| Nine Inch Nails |

| Sound Tribe Sector 9 |

| Ho99o9 |

| The 5,6,7,8’s |

| DT8 |

| The 5,6,7,8’s |

| Seven Mary Three |

| Zero 7 |

| School of Seven Bells |

| Avenged Sevenfold |

| School of Seven Bells |

| L7 |

| 7 Seconds |

| 7 Year Bitch |

| Shed Seven |

| The 5,6,7,8’s |

| Six Organs of Admittance |

| Slow Six |

| Appollonia 6 |

| Eve 6 |

| Sixpence None the Richer |

| Three Six Mafia |

| Sixx:AM |

| Six Feet Under |

| Nikki Sixx |

| Vanity 6 |

| V6 |

| Delta 5 |

| The 5,6,7,8’s |

| Five |

| Pizzicato Five |

| Five Finger Death Punch |

| Maroon 5 |

| Five Iron Frenzy |

| Ben Folds Five |

| The Jackson Five |

| MC5 |

| Family Force 5 |

| US5 |

| Dave Clark Five |

| Section 5 |

| B5 |

| Count Five |

| 5 Seconds of Summer |

| Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five |

| Jurassic 5 |

| John 5 |

| We Five |

| The Five Satins |

| five star |

| Gang of Four |

| Four Tet |

| The Four Seasons |

| The Four Tops |

| The Brothers Four |

| The 4-Skins |

| The Four Pennies |

| The Fourmost |

| 4 Non Blondes |

| 4 Jacks and a Jill |

| Funky 4*1 |

| Unit 4 + 2 |

| The Three O’Clock |

| Dirty Three |

| Fun Boy Three |

| Seven Mary Three |

| 3 Leg Torso |

| Bike For Three! |

| Three Mile Pilot |

| Dirty Three |

| Mojave 3 |

| Opus III |

| Alabama 3 |

| Three Dog Night |

| Three Doors Down |

| 3 Mustaphas 3 |

| 3 Mustaphas 3 |

| Three Six Mafia |

| Three Days Grace |

| 3LW |

| The Three Degrees |

| Spacemen 3 |

| Timbuk 3 |

| The Juliana Hatfield Three |

| 3T |

| Fun Boy Three |

| The Big Three |

| 3 Colours Red |

| Secret Chiefs 3 |

| Two and a Half Brains |

| Boyz II Men |

| Two Gallants |

| U2 (Sorry Bono) |

| Soul II Soul |

| Two Door Cinema Club |

| The Other Two |

| Aztec Two-Step |

| M2M |

| Two Man Sound |

| 2 Live Crew |

| Unit 4 + 2 |

| 2 Chainz |

| Secondhand Serenade |

| 2 Minutos |

| 1-2 Trio |

| 2wo |

| RJD2 |

| The Other Two |

| 2:54 |

| Faith + 1 |

| Oneohtrix Point Never |

| Doseone |

| One Republic |

| One Night Only |

| One Direction |

| KRS-1 |

| The Only Ones |

| The Lively Ones |

| Funky 4*1 |

| 1-2 Trio |

| One Dove |

| Third Eye Blind |

| Third Ear Band |

| The Sixths |

| Eleventh Dream Day |

| 13th Floor Elevators |

| Zero 7 |

| Remy Zero |

| Edward Sharp and the Magnetic Zeros |

| Authority Zero |

| Zero Boys |

| The Minus Five |

D.A.

D.A.