interview by Carl Slaughter

Jeanne Cavelos is a writer, editor, scientist, and teacher. Her love of science fiction led her to earn her MFA in creative writing. She moved into a career in publishing, becoming a senior editor at Bantam Doubleday Dell, where she created and launched the Abyss imprint of innovative horror and the Cutting Edge imprint of noir literary fiction. She also ran the science fiction/fantasy publishing program. In addition, she edited a wide range of fiction and nonfiction. In her eight years in New York publishing, she edited numerous award-winning and best-selling authors and gained a reputation for discovering and nurturing new writers. Jeanne won the World Fantasy Award for her editing.

Jeanne Cavelos is a writer, editor, scientist, and teacher. Her love of science fiction led her to earn her MFA in creative writing. She moved into a career in publishing, becoming a senior editor at Bantam Doubleday Dell, where she created and launched the Abyss imprint of innovative horror and the Cutting Edge imprint of noir literary fiction. She also ran the science fiction/fantasy publishing program. In addition, she edited a wide range of fiction and nonfiction. In her eight years in New York publishing, she edited numerous award-winning and best-selling authors and gained a reputation for discovering and nurturing new writers. Jeanne won the World Fantasy Award for her editing.

Jeanne has had seven books published by major publishers. Her last novel to hit the stores was Invoking Darkness, the third volume in her best-selling trilogy The Passing of the Techno-Mages (Del Rey), set in the Babylon 5 universe. The Sci-Fi Channel called the trilogy “A revelation for Babylon 5 fans. . . . Not ‘television episodic’ in look and feel. They are truly novels in their own right.” Her book The Science of Star Wars (St. Martin’s) was chosen by the New York Public Library for its recommended reading list, and CNN said, “Cavelos manages to make some of the most mind-boggling notions of contemporary science understandable, interesting and even entertaining.” The Science of The X-Files (Berkley) was nominated for the Bram Stoker Award. Publishers Weekly called it “Crisp, conversational, and intelligent.”

Jeanne has published short fiction and nonfiction in many magazines and anthologies. The Many Faces of Van Helsing, an anthology edited by Jeanne, was released by Berkley in 2004 and was nominated for the Bram Stoker Award. The editors at Barnes and Noble called it “brilliant. . . . Arguably the strongest collection of supernatural stories to be released in years.”

Jeanne created and serves as primary instructor at the Odyssey Writing Workshop. She is also an English lecturer at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire, where she teaches writing and literature.

She talks to Diabolical Plots‘s Carl Slaughter about getting into the trenches with writers.

More information about her and the workshop:

www.jeannecavelos.com.

www.odysseyworkshop.org.

(Pictured here with author Robert J Sawyer.)

CARL SLAUGHTER: WHY ASPIRING WRITERS?

JEANNE CAVELOS: As a writer critiquing other writers while getting my MFA in creative writing, and then at Bantam Doubleday Dell, working my way up from editorial assistant to senior editor, I found that I loved working with writers, helping them to make their work the best it could be. Identifying the strengths and weaknesses in a piece, and coming up with possible ways to address those weaknesses, is a lot like

solving a puzzle. For me, this is extremely satisfying. And when the light bulb goes off for the writer, and he revises the piece with this new understanding and radically improves the work–I am so happy for his success. I love helping writers to improve. So when I left publishing to make more time for my own writing, I wanted to continue to be able to work with writers. That’s why I started Odyssey.

CARL: WHY A WORKSHOP?

JEANNE: A writer usually can’t make dramatic improvements to his work by writing on his own. You can improve, but progress tends to be slow. To make dramatic improvements, you generally needs three things: first, a greater understanding of the elements of fiction and the tools and techniques that allow you to manipulate them in a powerful way; second, practice using these techniques; and third, feedback to reveal whether you are successful in using the techniques.

The Odyssey Writing Workshop focuses on providing these three things. We spend about 2 1/2 hours each day in lecture and discussion, so over the six weeks, we cover all the elements of fiction, pitfalls to avoid, and techniques that can create powerful, memorable stories. Daily writing exercises, as well as writing your own stories, help you put these concepts and techniques into practice. Then the workshop provides feedback on how you are doing.

Often writers, working alone, will read books on writing, but that knowledge won’t be incorporated into their work. There is great power to devoting oneself solely to one’s writing for six weeks, hearing lectures on writing, writing, reading the work of others and providing feedback. Doing all of these at once helps to incorporate the concepts and techniques into one’s writing process.

CARL: WHY ON SITE INSTEAD OF ONLINE?

JEANNE: Odyssey does offer online classes each winter. They are focused on specific writing topics and aimed at writers of a particular skill level.

We hold live class sessions via Web conferencing software, to create the most immediate, interactive experience possible. Writers have found these very helpful.

But they aren’t the same as being in the “Odyssey bubble,” as the class of 2013 called it, an intense, private place filled with writers and

focused on writing, where the outside world does not intrude. Just getting away from “real” life is a huge help in putting all one’s energy toward improving one’s writing.

CARL: WHAT DID YOU LEARN FROM YOUR MFA IN CREATIVE WRITING THAT HELPS YOU AS A CRITIQUER?

JEANNE: I became much more aware of style and learned the different ways to manipulate words and sentences to create different effects. That was extremely valuable. Many genre writers don’t have style very high on their list of things to think about, so I try to make them more aware of their style, of the choices they’re making, and then offer them some other possibilities that may be more effective. For example, many developing writers use a similar sentence length throughout, when instead they should be manipulating sentence length to better support the action and emotion of each moment.

CARL: WHAT DID YOU LEARN AS AN EDITOR THAT HELPS YOU AS A CRITIQUER?

JEANNE: I learned a great deal as an editor. Reading submissions reveals many common weaknesses of developing writers, so I am very aware of them and can point them out in a critique, as well as warn writers away from them in advance. For example, starting with a character sitting and thinking about his life, or standing and thinking about his life, or driving and thinking about his life, indicates the writer has started in the wrong place and doesn’t understand the requirements of an opening, or how exposition (background information) should be incorporated into a work. Working with writers on manuscripts that we were going to publish taught me how much better a good piece can become with revision.

CARL: WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS WRITERS HAVE AND HOW TO YOU ADDRESS THOSE MISCONCEPTIONS?

JEANNE: Writers at different levels of development have different misconceptions. Many of those who attend the Odyssey workshop arrive thinking that they know almost everything about how to write and the techniques to use. They are mainly looking for feedback on how well they are incorporating that knowledge into their work. From what they’ve told me, within a few days, they realize that there is a huge amount they didn’t know. Then they get very excited and start soaking up as much as they can.

CARL: WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON WEAKNESSES WRITERS HAVE AND HOW DO YOU HELP THEM OVERCOME THOSE WEAKNESSES?

JEANNE: The most common is lack of a strong plot. This usually arises because a writer starts a story with no idea where it’s going, writes a draft, and then declares the story done. There’s nothing wrong with starting without knowing where you’re going. But if you start without knowing the end, chances are the story will lack unity, focus, a strong character arc, and a strong plot. So once you know the end, then you probably need to toss out everything else and figure out what the beginning and middle ought to be, to lead to that end. Most writers, on hearing this, become more open to planning ahead and trying to discover the ending before beginning the draft. I explore different techniques with writers to try to find the right one for them.

Another common problem is writers who don’t want to let anything bad happen to their protagonists. By discussing other stories that they enjoy, and the bad things that happen to those protagonists, I try to help them see the necessity of suffering. Something important needs to be at stake for the protagonist. He needs to struggle and be challenged by the events, and if he is lucky enough to have a happy ending, he needs to pay a price for it. Many writers have weak or flat characters in their stories. The characters have a couple of superficial characteristics, and that’s it. The main character lacks a feeling of depth, of hidden dimensions, of reality. There are some great techniques writers can use to add depth to a major character. One simple method is to use the Johari Window on your character.

Often the protagonist is a stand-in for the author, and since most authors spend a lot of time sitting around, thinking, and writing, their stand-ins tend to be passive. Many writers just need to learn that the protagonist needs to have a goal that he is struggling to achieve. Even if the goal is sitting on the couch, there must be obstacles and other forces he must struggle against to stay on that couch.

CARL: HOW MUCH EMPHASIS DO YOU PLACE ON A WRITTEN CRITIQUE VERSUS NOTES ON THE MANUSCRIPT VERSUS ONE ON ONE SESSIONS?

JEANNE: All of these are important components for learning and improving. One-on-one meetings are invaluable, because they allow us to discuss larger issues that haven’t come up in critique, to address questions, to chart progress and remaining challenges, and to discuss how changes to the student’s writing process have worked and explore new changes to make. It’s also important for me to connect personally with each writer, to understand his needs and do what I can to help him.

CARL: HOW MUCH EMPHASIS DO YOU PLACE ON PRODUCTIVITY VERSUS QUALITY, HOW MUCH ON REVISION, HOW MUCH ON CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT, PLOT STRUCTURE, STYLE/VOICE, ETC?

JEANNE: Students at the workshop need to submit six pieces of fiction over the six weeks (and two before the workshop begins). This requires a greater level of productivity than most students have achieved. But they rise to the occasion and produce some amazing work. I think it’s very important to be writing each evening, after hearing the information in the lectures that morning. This helps the concepts to be incorporated into the student’s writing process. Writing multiple pieces allows the students to try and try again to incorporate a particular technique or make progress with a certain element. And that’s exactly what they need to do. Quality sometimes suffers as students become exhausted–you will never work harder in your life than you work at Odyssey–but sometimes the greatest breakthroughs occur at a 3 AM writing session.

I strongly encourage revision, since in my experience most writers don’t revise nearly enough. Students can submit revisions of pieces they previously had critiqued. I encourage them to submit a revision to a different audience. For example, if they had the initial version critiqued by the entire class, they could have the revision critiqued privately by a guest lecturer, or vice versa.

As for character development, plot structure, style/voice, all of the elements of fiction are important to a powerful, unified story. I would say I stress plot and character a bit more than the rest, since they are the building blocks, and if they’re not working, it’s hard to have a successful story.

CARL: DO YOU RECOMMEND AN OUTLINE AND CHARACTER PROFILES FOR EVERY STORY, ESPECIALLY NOVELS?

JEANNE: Every writer is different, so I would have different answers for different writers. But unless you are a genius at instinctive plotting, it would be unwise to write a novel without some sort of outline, even if the outline has just four lines, specifying the beginning of the novel and the end of each of your three acts. Still, some writers are unable or unwilling to work with an outline, and that’s okay; it just means they need to be willing to do *lots* of revision. A useful tool in these cases is to outline as you go. Write a scene and then add a line describing what happened in it to your outline. Then you will have an outline when you finish your draft, and you can examine it and see how to strengthen your plot.

I find character profiles overrated. They are helpful for some writers, but in most cases, writers create elaborate profiles and then they start writing and the character behaves in an entirely different way. I think you need a basic, core sense of who the character is, what he wants, and why he wants it, before you start writing. Beyond that, I think the most helpful thing for many writers is to note different traits or facts about the character as they are writing the story.

CARL: DO YOU EVER REWRITE A PASSAGE FOR A WORKSHOP STUDENT? IF SO, IS THIS STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE OR LAST RESORT?

JEANNE: I will rewrite a sentence, but not a passage. Rewriting a passage would feel like telling the author what the story should be. That’s not my job. My job is to try to figure out what the author wants the story to be, and then offer feedback and suggestions to help him make that story as strong as possible.

CARL: WHY ALLOW OTHER WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS TO CRITIQUE STORIES? IS SOMEONE QUALIFIED TO CRITIQUE IF THEY HAVE NO EDITING EXPERIENCE, DON’T HAVE A DEGREE IN CREATIVE WRITING, AREN’T FULL TIME, CAREER WRITERS?

JEANNE: Most Odyssey students these days have critiqued a fair amount before arriving at Odyssey. But whether they have or not, it is a key skill they need to develop to improve their own writing. Many authors think that critiquing someone else’s work is a favor they do for the other writer, so that the other writer will critique their work. Nothing could be further from the truth. Critiquing someone else’s work helps you to develop your critical writer’s eye. It helps you to analyze a story and figure out what is working and what isn’t working. It allows you to come up with possible solutions to improve the weaknesses. Once you do this for long enough, you can begin to apply this critical writer’s eye to your own work, seeing the strengths and weaknesses as if it’s a piece written by someone else, and coming up with solutions to solve your problems.

Critiquing is also a great help in that it forces students to apply the theories and concepts discussed in class to actual stories. For example, when they realize that a story isn’t holding their attention and that they don’t care what happens, they are forced to step back and try to understand why. Then they see that the protagonist isn’t struggling to achieve a goal, and they realize–in a way much more powerful than me just telling them this in class–how important it is for the protagonist to have a goal and to be struggling toward it.

Going back to your question, I don’t think people need any particular qualification to critique. They need to know and follow the guidelines of the particular workshop. And the more they know about writing, the more specific and helpful their critiques will probably be. But most anyone off the street can read a story and say whether he likes it or not, and that’s valid criticism. It’s not terribly helpful, in that it provides no specific direction for the author to take to improve the story, but it is honest.

CARL: IS SHOW INHERENTLY BETTER THAN TELL, IS ACTIVITY INHERENTLY BETTER THAN DIALOG, ARE ACTIVITY AND DIALOG INHERENTLY BETTER THAN NARRATIVE, ARE FIRST, SECOND, OR THIRD PERSON INHERENTLY BETTER THAN THE OTHER TWO, DO YOU HAVE TO OPEN WITH THE MOST DRAMATIC SCENE AND THEN REWIND, DO YOU HAVE TO LIST THE CONTENTS OF A ROOM OR DESCRIBE A CHARACTER’S PHYSIQUE OR CLOTHING, DOES THE STORY HAVE TO ORGANIZED LIKE A 3 ACT PLAY, ARE DREAM SEQUENCES AND INFO DUMPS INHERENTLY WEAK TOOLS, ETC?

JEANNE: Wow–that’s a lot to cover. You’re listing a bunch of writing principles that some people assert, so let me talk about principles in general. There are many principles by which stories work. A protagonist should struggle to achieve a goal. A protagonist should have an internal conflict and an external conflict, and the internal conflict should be resolved before the external conflict. The story should lead to a permanent change in the protagonist. And so on. Many successful stories follow these principles. But there are also many successful stories that break one or more of these principles. So saying that you must do something, or that one thing is better than something else, is needlessly restrictive. Sometimes to serve the story, you need to break one of these principles. You can do whatever you can get away with. What is most important is that you know the principles and mindfully make the choice to break one of them, because it is necessary for the good of the story. Breaking a principle usually means you take away some pleasure that the reader expects to have when reading a story. That means you need to offer the reader a pleasure of equal or greater value to make up for the one you’re taking away.

So if a story is entirely dialogue, for example, and you are taking away the pleasure we would normally have of feeling like we’re in a particular place and experiencing vivid sensory impressions of it and of the characters, then you must offer us something else in exchange, such as incredibly tense dialogue and layered characters, and dialogue that perhaps evokes sensory impressions, so we have something to picture as we’re reading.

As for what the specific principles are that writers should usually follow, I disagree with many of those in the question. Showing is important and should usually be used much more than telling, but each has its place and purpose, and you need to use each when it serves the story. Similarly, action, dialogue, and narrative all have their purpose and should be used where necessary to serve the story. Each POV has its strengths and weaknesses (and first person is horribly overused by developing writers), but you need to choose the best POV for the story. The most dramatic scene should almost always be the climax, not the opening. Starting with the most dramatic scene and then rewinding tells me that the rest of the story is probably boring. Descriptions need to be used when they serve the story. Three-act structure is great for many stories, but not for all of them. Dream sequences and infodumps are usually not good ideas and I discourage them, though some writers can make them work.

CARL: HERE’S ONE I HEAR A LOT: THOU SHALT NOT CHANGE THE POV IN THE MIDDLE OF A SCENE. IS IT REALLY CONFUSING TO THE READER TO CHANGE THE POV IN THE MIDDLE OF A SCENE?

JEANNE: Yes, it usually is. If you have established at the beginning that you are writing in an omniscient viewpoint and dipping into the heads of different characters, then it’s fine to continue to do so throughout the story. The problem is that it’s difficult to do this gracefully. You need to establish the voice of your omniscient narrator, establish the location of the POV “camera,” and then move the camera so smoothly and effortlessly that the reader doesn’t notice what you’re doing. You would approach the character, move into the character’s head, spend however long you want there, then slowly move out, move toward another character, and so on. C. S. Lewis generally does this well in THE LION, THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE. But you’ll find many more examples of it being done poorly, which leads to the reader being confused or not feeling settled in the scene.

CARL: ANY NEW PROJECTS OR SERVICES AT ODYSSEY? ANYTHING ON THE HORIZON?

JEANNE: We’re working on a couple of things that I can’t talk about yet, but I hope will offer some great help to writers. Right now, in addition to our summer workshop, we offer winter online classes (which will be announced in October with application deadlines in December), a critique service so you can get professional feedback on your manuscripts, and many free resources, including monthly podcasts, blog posts, writing and publishing tips, a newsletter, and more. You can access all of these through our website.

We also were able to provide three scholarships to Odyssey workshop students this past summer, due to the generosity of an Odyssey graduate, and it looks like we’ll be offering those scholarships for future workshops.

CARL: WHAT DO YOU RECOMMEND FOR WRITERS WHO CAN’T AFFORD A WORKSHOP, CAN’T GET LEAVE FROM WORK, CAN’T TRAVEL, ETC?

For many people, attending a six-week in-person workshop is just not possible. I used to get many emails from writers in the situations you mention, asking Odyssey to offer them something to help them improve their work. That’s why we started the critique service in 2006 and the online classes in 2010.

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

His training is in journalism, and he has an essay on culture printed in the Korea Times and Beijing Review. He has two science fiction novels in the works and is deep into research for an environmental short story project.

Carl currently teaches in China where electricity is an inconsistent commodity.

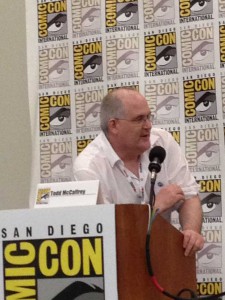

affrey has no plans to stop writing Pern books. He plans to sanction a movie but he wants the screen version done right rather than done quickly.

affrey has no plans to stop writing Pern books. He plans to sanction a movie but he wants the screen version done right rather than done quickly. CS: Do you have a longterm outline for the series or do the plots come one book at a time?

CS: Do you have a longterm outline for the series or do the plots come one book at a time? CS: What kind of feedback have you gotten from the fans? What characters, eras, themes, plots do they like/dislike? What scenes or plot twists or ending do they strongly approve of or disapprove of? Have they asked you to revisit certain characters or certain eras?

CS: What kind of feedback have you gotten from the fans? What characters, eras, themes, plots do they like/dislike? What scenes or plot twists or ending do they strongly approve of or disapprove of? Have they asked you to revisit certain characters or certain eras? Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

In the 1990s,

In the 1990s,

CS: There were several speculative fiction imprints at the time Pyr was launched.

CS: There were several speculative fiction imprints at the time Pyr was launched.