From: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

To: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

Date: 2160-11-11

Dear Ziza,

You already know what this is about, don’t you, dear Sister? The robot raccoons I found clamped along my ship’s hull during this cycle’s standard maintenance sweep?

Oh, come on. Really? You know I invented that hull sculler tech, right? They’ve got my corporate logo etched into their beady red eyes so my name flashes on all the walls when their power is low. I admit some of your upgrades were… novel. Like the exoshell design–I’ll never understand your raccoon obsession. Impractical, but points for style. I hadn’t thought you could fit a diamond drill into a model smaller than a Pomeranian’s skull, so congrats on that. Not that they made much progress chewing through my double-thick hull, but I’ll give credit where credit’s due.

Still, it was unsisterly of you, and it’s not going to stop me from dropping the terraforming nuke when I get to Mars. Come to grips with reality, sister: you’re in the wrong. You always have been, ever since we were girls. Especially since Mumbai accepted my proposal for Martian settlement. Not yours.

I’m sending back the robot raccoons in an unmanned probe. Back, because yes, I’m still leagues and leagues ahead of you. I only lost a day cleaning up the hull scullers. I’ve kept the diamond drills. I bet they’ll chew right through that Martian rock.

I’ve also included a dozen white chocolate macadamia nut cookies, because I know it’s your birthday tomorrow. Happy birthday!

Now go home.

Love your sister,

Anita

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

To: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

Date: 2160-11-12

Dear Anita,

Remember that summer when Father dropped us off at the northern rim of the Poona Crater on Mars? Alone. For two weeks. “This rustic camping trip will be a great learning experience,” he said. “My precious daughters will bond.”

When I learned that there were no pre-fab facilities and that we were responsible for erecting our own dwelling, sanitation pod, and lab, I started plotting ways to poison our father. You, on the other hand, I am still convinced, were determined to thoroughly enjoy the experience just to spite me.

But Father was a conservationist, and now that I am older, I can appreciate that he was trying to instill that same spirit in us. “Not all life jumps out and bites you in the butt,” he used to love to say. And we learned the truth of that when we unearthed a family of as-yet-undiscovered garbatrites in the red dust on one of our sand treks.

We spent hours watching them under high magnification under the STEHM, trying to communicate with them, recording their activities and creating hypotheses about the meanings of their habits. I have to admit, there was a point when I stopped cursing father and started to secretly thank him. And where I sort of, kind of, could maybe see why you weren’t so bad after all.

I don’t think I’d ever seen you so dedicated to anything before this. You missed meals and stayed up throughout the night trying to communicate with the elder garbatrite. The one you named Benny. Exhausted, you fell asleep at your desk and left the infrared light on too long and effectively fried the poor critter. You cried for days and you even held a formal funeral for Benny, something his fellow garbatrites didn’t seem too pleased about.

With that in mind, how could you possibly want to drop a terraforming nuke on a planet you and I both know is already teeming with life? Creating a new habitable world only has merits if it’s not already inhabited.

If you won’t see reason, then I’ll just have to make it impossible for you. The Council for Martian Settlement may have accepted your proposal, but let me remind you that I’ve never been keen on following the rules.

So, you found the hull scullers, eh? I knew those diamonds would distract you from my real plan. You’ve always been so… materialistic. But hey, someone has to be.

On another note, the cookies were to die for! They were even better than Mother’s, but I’ll never tell her that. I really appreciate you thinking of me. I have a proposal to make. On our next monthly meal exchange, I’ll make your favorite, a big old pot of Anasazi beans and sweet buttered cornbread, if you’ll send more of those cookies.

XOXO

Ziza

P.S. My sweet raccoonie-woonies, Bobo and Cow, liked the cookies too. They also send their love.

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

To: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

Date: 2160-11-15

Sister:

Come now, Ziza. Let’s not make me out to be some kind of villain. Of course I remember that summer. I remember how we licked the condensation inside our lab windows to stay hydrated because Father’s Orion Scout childhood romanticized survival stories. It’s the real reason we’re such die hard coffee drinkers nowadays. He ruined the taste of water for us.

And I remember the garbatrites. How could I ever forget? That dusty red boulder we found in the sandstorm provided just enough shelter to pitch our emergency pod while we waited out the squall. Nothing to do but talk with each other, or play with the STEHM. Which meant we chose the STEHM, obviously. It’s the closest look I’ve ever gotten at you, all those disgusting many-legged organisms crawling on your skin and hair, in your saliva, your earwax. You’ve always had an affinity for vermin.

But I’ll be forever grateful you suggested taking samples around the boulder. When we first saw the garbatrites, their tiny little dwellings drilled into rock like mesa cities–that might be the closest I’ve ever felt to you, each of us taking one eyepiece on the STEHM, our damp cheeks pressed together, our smiles one long continuous arc. When the light brightened or dimmed, they danced in little conga lines. We weren’t sure if it was art, or language. Is there really a difference?

There’s something I realized when Benny died. The sort of revelation you only have when you’re nudging together an atomic coffin beneath an electron microscope with tiny diamond tweezers just three nanometers wide: life is short. Life is painfully short, full of suffering and tragedy and wide, empty spaces. And those rare spots hospitable to life are just boulders tossed into an endless red desert, created by accident or coincidence. The only real good we can do in life is to spread out those boulders, minimize the deserts where we find them. Make a garden from dust. Plant our atomic coffins and let them bloom. Terraform whole planets, so we’ll have more than just the blue boulder of Earth.

That’s what you never understood, dear sister. It’s why when you spent your youth chasing pretty men, I betrothed myself to science, burned my hopes of human love in the furnaces of my ambition. Do you remember when Asante, my poor besotted lab assistant, proposed to me at the Tanzanian Xenobiology Conference? How I laughed! As if any children he could give me would approach the impact my terraforming nuke will make on our species. Never forget, Ziza, that this mission is my life’s work, my legacy. You will not stop me.

In other news, I got the Anasazi beans and cornbread, still warm and fresh in their shipping pod. How did you know I had the craving? That was a kindness. I remembered you while making salaat today.

I was less pleased about the virus installed in the shipping pod’s warming program. Nice try, but I saw through that in about five seconds. Here’s a tip: next time, beta test it on all the shipboard systems I invented, not just the navigation. My sanitation program does more than filter my own crap.

I’m sending you an e-manual on Programming 101, and an ordering catalogue for Anita Enterprises in case you’d like to support the family business.

XOXOXO,

Anita

P.S. Go home.

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

To: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

Date: 2160-11-28

Anita,

It’s been nearly two weeks since we last spoke, and of course, you know why. When you told me to go home, I knew that you were serious, but I never thought you’d resort to using the health and welfare of our dear mother as bait to get me to turn around and head back to earth.

I’m still trying to figure out how you managed to simulate for video not only our mother’s countenance, darkened and marred by some mysterious illness, but her voice, the cadence like smooth stones tumbling in water and her accent. When she pleaded for me to return home, telling me that she was afraid to die alone, of course I turned back.

How much time did it take for you to create those videos, one arriving each day, her looking progressively worse? The worst was that one video with her by the window in her study, Mount Kilimanjaro in the distance. It came on the third day. The sunlight that glinted through her silver hair, like icy filaments, made her look so painfully beautiful, yet it was not enough to erase the shadows beneath her eyes or the sadness in them.

A better question, I suppose, is “Why?” Why resort to that when you know how much Mother means to me, especially now that Father is gone? Are you still jealous of our closeness? Do you still believe she loved me most?

Not that you deserve to be, but I’ll let you in on a secret. I used to believe Mother loved me more than you as well. One day, I must’ve been about twelve, in my pathetic need to always be reminded that I was loved and cherished, I asked her why she loved me more than you. I waited a few moments, as she looked skyward, it seemed, for the answer. I was sure she’d say it was because I was more beautiful, more kind, smarter, that I had a more generous spirit, because truth be told, these things are true. But she didn’t say that. Mother told me that she did not love me most. Nor did she love you more than me.

Then why do you spend so much more time with me than Anita? Why do you kiss me goodnight and not her? I numbered all the things she did for me and not you. Do you know what she said?

Because you need me more than Anita.

In her way, which was always kind yet honest, Mother was telling me that you were the stronger of the two of us. But now, I wonder. Would a strong person use her sister’s weaknesses against her just to win? This was a low blow, Anita.

By now you’re probably wondering how I eventually figured out that the videos from Mother were merely a cruel ploy to get me to go back home without a fight. It was the video from Day Eight.

Mother lay in bed, slight as a sliver of grass. When her image popped up on the view screen my heart felt like it was trapped in a vice. She reached out. A tear traveled from the corner of her eye toward the pillow. She coughed, then called out my name. Her voice was so soft, so small and weak.

“Please hurry home, Ziza,” she said. “I don’t want to die without laying eyes on my favorite girl at least one more time.”

Favorite girl? No, Anita. Our mother never would have said that.

You think you’re so smart. You think you know everything. Yet, you don’t know kindness or humility. You don’t even know your own mother.

The decision to dedicate your entire life to science was an error. Life is so much more than entropy, polymerisation, and endothermic reactions. You really can have your coffee and the cream too. You should have married Asante. He would have humanized you. He would have taught you to slow down and enjoy the precious little moments, that together they all add up to a great big life full of disappointments, yes, but also joy and love and mystery. He would have saved you from yourself and cold loneliness.

This is where I remind you that you know nothing about programming that I didn’t teach you. Anita Enterprises is the mega-conglomerate it is because of me, your older sister and mentor. If I wanted to shut down every system on your ship, including life support, I could. And believe me, after this latest stunt of yours, I’ve been giving that idea serious consideration. The fact that I haven’t sent a couple of torpedoes your way is a testament to my love for our mother. She’d be angry if I killed you. So, I won’t.

See you on Mars.

Ziza

P.S. Don’t start none, won’t be none.

P.P.S. Bobo and Cow are very displeased with you.

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

To: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

Date: 2161-01-01

Ziza,

It’s been weeks since I last wrote, but you haven’t been far from my thoughts. Far from it.

While I continue toward the planet, I’ve been passing the time on my escape pod making a list of all the reasons I hate you, numbered and ordered least to greatest. It’s a long long list, forever incomplete. A sister’s hate is like the heat death of the universe: infinitely expanding, eternal, the last flame burning in this cold, barren desolation where God abandoned us.

Reason #1,565: I hate the way you eat popcorn with chopsticks to keep your hands clean. Are you too good even for butter smudges?

Reason #480: I hate how you laugh at bad jokes. Puns aren’t actually funny, Ziza. Everyone outgrew “why did the chicken cross the road” after elementary school.

Reason #111: Blue eye shadow. Self-explanatory.

Reason #38: “Don’t start none, won’t be none.” Really? Better knock that shit off. Like you’re not an adult responsible for her own actions.

Reason #16: I hate how Mother named you after herself, like you were the pinnacle of all her hopes, while I was named to placate our pushy grandmother.

Reason #15: I hate how you always laugh at me.

Reason #10: I hate how your favorite animal is the raccoon. You only picked it because it’s endangered. You can’t resist a lost cause, even if you don’t actually want to do anything useful about it.

Reason #9: Seriously, blue eye shadow.

Reason #4: That last family dinner we had before Father died, when we took the shuttle out to the Moon to picnic on Mons Agnes while we watched the Perseid meteor shower dancing bright upon Earth’s atmosphere like the footsteps of angels. Mother brought her heirloom silver for the occasion; I think we all knew in our hearts it was a special trip. We’d agreed for Father’s sake to get along, just for a few hours. He hated how we fought, how we picked at each other like children picking old scabs that won’t heal. Do you remember the white curling through his black hair? His cheeks sunk deep by the chemo? He wanted to dish up the jasmine rice and flatbread himself. His hands trembled so badly the peas rolled onto Mother’s quilt beneath the picnic pop-up, just skirting the regolith.

We both know I wanted to talk with him about the inheritance. I just wanted my share, my 50/50 split, but Mother was so concerned about poor helpless Ziza, who had run into such tough times after college, chasing after pretty men and idealistic wide-eyed save-the-raccoons causes that she needed a larger cut to keep up her lifestyle. Anita Enterprises cost me everything while all you ever did was chase your girlhood dreams of love and happy endings.

We were having such a great time. Your useless pet raccoons were recharging their solar batteries in your lap. Father told us stories of his childhood, how they didn’t even have a family shuttle when he grew up, and you could only sleep rough in wild places like Antarctica’s rocky plains. Mother held his hand and kissed him, love shining in her eyes. No matter how sick he got, he was still the dark-skinned 17-year-old godling she’d met on the road to Mount Kilimanjaro in their youth. We even tolerated a few of your puns.

It would not last. I volunteered to scrape the leftovers into the recycler at the service booth down the path. It was so close, I didn’t bother to bring a communication device. You deny it, but we both know you followed me. You used the Moon’s lower gravity to pile those rocks against the door while I did my chores inside. When I tried to leave, the door wouldn’t budge. I could only watch my family from the viewing port, my mother and sister and dying father laughing together, though I couldn’t hear them. I screamed and pounded the window, but nobody noticed from the picnic pop-up. No one could hear me through the vacuum of space.

How can I ever forgive you that prank, those precious minutes of our father’s health ticking away, and me unable to be there? How can I forgive that lost opportunity, those memories that should have been mine to cherish, to bear me up when I wake at night so desperate to feel his whiskered kiss on my forehead, his voice telling me he’s so proud of me, proud of everything I’ve done?

This is why I hate you, Ziza. This is why I can never stop hating you.

Reason #2: Those diamond drills in your robot raccoons weren’t just drills. That cornbread pan wasn’t just a pan. You know what, Ziza? In spite of everything else, I only sent you back to Earth with those fake videos to protect you from yourself, and keep you out of harm’s way. Because despite this whole list, part of me still loved you, stupid as it sounds. Maybe it’s because you’re named for Mother. But you tried to dump me into the vacuum of space, Sister Dearest. You tried to murder me in my sleep. You activated the wafer computer in the pan’s false bottom, hacked my defenses, and the drills turned my hull into cheese by the time I woke up. If I hadn’t mounted the terraforming nuke to the escape pod… but I did.

Reason #1: Did you ever love me? Ever, Ziza? I’m not filling this one out yet, because I don’t think I’ve yet hated you as much as a woman can hate her sister. Not yet. But I will.

So I’m going to tell you something else you don’t yet know: On the wreck of my shuttle, scraping by on the last of my life support, are a dozen rare raccoon specimens. I was going to release them on Mars after the terraforming ended so they could colonize a safe place far from any predators. My shuttle is set to self-destruct in two days’ time. If you leave your current course, you might just have time to save them. Let’s find out what you care more about: helpless garbatrites, or near-extinct raccoons.

The shuttle also contains an urn with Father’s ashes, wrapped in extra scarves in the top hatch in my quarters. Mother asked me to scatter them on the planet because Father had so many happy memories of camping there with his daughters. I didn’t have time to rescue it when I had to abandon ship a few days ago.

I don’t have that one on my list yet. Better go add it now.

Hate you always,

Anita

P.S. Why did Ziza fly across the solar system twice? Because she was a double crosser. Get it?

P.P.S. Happy New Year, by the way.

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

To: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

Date: 2161/01/02

Anita,

By now you’ve probably realized that regardless of your efforts, your escape pod’s trajectory is no longer Mars. You are now on an intercept path with me. I know that you must be seething, cursing my name, praying for my damnation (you’ve always been so dramatic), but give me the opportunity to explain.

Your ship was never in danger. The plan was that once you entered in new coordinates to anyplace other than Mars, preferably home, the diamond drills would have set about repairing the holes they’d created in the hull of your ship. Genius ancillary programming, if I do say so myself. All you had to do was turn around. But you, with your flare for the dramatic and unwillingness to give up, even when you know you’ve lost, decided to jump ship and make the rest of the voyage via the escape pod.

The escape pod. The escape pod with only half the power you’ll need to complete the trip to Mars. At the rate you’re going you’ll be one hundred and three before you even break orbit. If you paid as much attention to the details as you do the drama, you might have remembered that.

Why couldn’t all your hot hate keep those poor raccoons warm as your abandoned ship plunges onward toward the cold outer depths of space, too long and too far for either of us to go? I won’t be able to save those raccoons, nor Father’s ashes, because I will be saving you.

You can thank me later.

Your last message, so thick with evil enmity for your only sibling in the galaxy, reminded me of Tariq, the only man I ever considered staying with for a lifetime. I’ve tried over the last forty-three years, without an iota of success, to tangle and finally lose my memory of him among the many others. He was brighter than Sirius and sweeter than lugduname, at least to me. I know that long-legged bird wasn’t perfect, he chewed with his mouth open and, truth be told, he wasn’t very bright but he loved me without reserve.

You didn’t like him at first. You called him a “pretty, useless thing”, because he didn’t have the same knack for business or driving ambition for more, that you did. He was an artist and liked to create beautiful things, to experience the delights of life with all of his senses exposed and ready.

It was through your senses that he finally won you over. So thoughtful was he, that knowing your dislike for him, he still surprised you with your favorite, hot homemade waffles, on your birthday.

When I broke off the engagement with him only a week later, you, who had hated him all along, refused to speak to me for months. You said I’d made the biggest mistake of my life. You called me a fool.

I never told you why I broke off the engagement. And I bet you never knew that even now, there are sleep cycles when instead of sleep, I lay awake imaging how happy I’d be today had I not broken poor Tariq’s heart.

I broke off our engagement because of your Reason #1. In answer to your question, I love you more than breath itself, baby sister.

Tariq said to me one day, as we lay beneath the sun in a field of cool holo-grass, “Any sister who would waste her dying father’s final hours arguing over an inheritance is surely too selfish to bear.” He took my foot in his hands and kneaded my heel expertly. “I’m willing to tolerate Anita, my love, because of you.”

I said nothing to this for a while, mostly because the foot massage was so exquisite that it stole my breath and crossed my eyes. But when he was done, I politely slipped on my shoes, clapped off the holo-vision, and asked him to leave.

“If you love me, you must love my sister too. Anything less is unacceptable,” I told him.

So you see, silly sister, you can hate me a million times, but no matter what, I’ll still love you, even though you don’t deserve it. God, you’re such a brat.

Ziza

P.S. Are you seriously pouting about your name? Mother should have named you Shakespeare because you’re nothing but drama.

P.P.S. I didn’t pile those rocks against the door. That was Bobo and Cow. They were just trying to play hide and seek with you. I guess my sweet raccoonie-woonies won that round.

P.P.P.S. Why did the raccoon cross the solar system? To keep her sister’s paw off Mars.

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

To: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

Date: 2161-01-11

Dear Ziza,

Greetings from Mars.

Don’t worry. Nothing has changed. I have regretfully failed to deploy the terraforming nuke. My mission has failed, for now.

Perhaps even before you read this message, GalactiPol will be taking you into custody. I called them when my escape pod veered off course, when the navigation stopped responding to my counter-hacks. You might have forgotten in your rashness that the Mumbai Council for Martian Development endorsed my plan for terraforming, and that I was their agent. Interfering with my mission meant meddling with the Coalition of Humankind itself.

I didn’t call GalactiPol sooner because I wanted to beat you at your own game. So few people in this huge, empty universe can even approach my creativity and intellect. You’ve always pushed me to the greatest apex of my brilliance. I’m never as inventive as when you’re scheming to ruin me. But the thought of losing Father’s ashes into the void of space… well, it gave me no rest. He doesn’t deserve that, not at our hands. I’d hoped you’d fetch the urn, but instead I’m calling an end to our battle of wits.

GalactiPol scooped up my escape pod and listened to my account of your wrongdoings. They have dispatched a salvage vessel to my wreck, and an armed cruiser to arrest you. Unfortunately, I made a fatal mistake: the raccoons. As you well know, I did not have authorization to remove these endangered creatures from Earth.

So they’ve arrested me too. I’ve been dropped on Mars for safekeeping while they run the raccoons back to Earth. They’ve dispatched another cruiser to your coordinates. Soon they will bring you here too, dear Ziza, and for the second time we’ll wander the sands together in this desert of red storms, with only wit and curiosity and mutual hatred to keep us alive until someone returns for us.

Did you know part of our old camp is still here? Somehow the shell of our mobile lab held up against the years. Probably because of the garbatrites. Remember we’d left the lab tucked in the shadow of their great stone. Apparently they liked it (perhaps for the way it holds warmth during the cold Martian nights) because they covered it in their tiny homes like a shipwreck bejeweled with coral and barnacles. When I turn on the lights at night, they dance along the seams in swirling shapes, carving microscopic paths through the dust coating, just as frail human biceps have pushed and moved the world until you can see their efforts from space. The Great Wall of China! The glittering glass megascrapers of Nigeria! How floating Melbourne glistens like a blue jewel in the dark, riding the waves forever, its flooded gondola channels sipping the ocean’s rise and fall! Our little lab is a world for these tiny creatures. They shout, We are here. We exist.

But let’s talk about Tariq. Now there’s an unhealed wound running to our cores. It’s true, Ziza, that you were always the prettiest. I am a plain woman, an experience you can never understand. Your beauty is a passport into people’s best nature. Everyone sees in you the face of an angel, and they give you an angel’s due. Well, any plain woman knows the converse is true, that we have to prove again and again our worth and goodness to a world that mistakes the grotesque for evil, the ungroomed for lazy, the fat for stupid.

Your Tariq, like all pretty men, suffered from the same assumptions. He was never as good to anyone as he was to you, Ziza Angel-faced. When he didn’t ignore me outright, he liked to pick on me for your amusement. He named me Yam Nose and Ogre Teeth, and when I protested, he laughed me off as too sensitive, as if I didn’t have a right to my dignity. People like him are cruel to girls like me in a thoughtless, automatic way, like they can’t imagine us having feelings any more complex than a dog’s. Yes, I detested him. But the day he made me waffles, throwing me one small, quiet kindness, I realized how happy he made you, that you intended to marry him. He’d be around our family a long, long time. I made my peace.

I am sorry you realized so late the flaw in him that was obvious to me from the first. But know, Ziza, that Tariq must accept responsibility for his own character. If you had married him, when you aged and your beauty began to fade, he surely would’ve turned that same cruelty on you. He may very well have been your soulmate, but take a hard look at your own soul, and ask whether you too mistake your angelic face for more than it is. You are merely human.

So come to Mars, Sister. Come to where this all started that summer our father wanted us to bond, back before we hated the taste of water, before we learned to despise each other in small ways and big. We cannot escape one another. Our hatred has been our brilliance, our secret genius, the harsh red desert that pushed and pinched and goaded us to build towers you can see from the Moon. Imagine what a lifetime of love might have accomplished

Come to Mars, Ziza. Scatter our father’s ashes with me. If we cannot make this place bloom with life, at least we can make it a little more dusty.

Anita

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

To: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

Date: 2161-01-11

Dearest Anita,

I can see the GalactiPol cruiser from my starboard viewport. Its black and gold stripes practically glow beneath the strobing orange beacon and make it look like a psychedelic bumblebee. Most people in my situation, facing detainment on Mars, endless expensive legal proceedings, possible time in prison, would be locked in the grips of fear and worry. Perhaps even shame. But not me. The one thought stuck in my mind, like a diptera fastened to sticky paper, is how beautiful that cruiser is and how excited I am to begin this second adventure.

It’s all about perception.

During that last picnic on the moon, when you were locked in the service booth, Father talked about perception. “Perception is everything. If you can project what you perceive it will become reality. You will believe it. More importantly, whether good or bad, everyone else will believe in your reality as well, and they will believe in you.” Not until I read your last letter did I realize how right Father was. And how wrong we have been.

In the mirror I’ve always seen the imperfect likeness of our mother, not quite as beautiful, not quite as kind, and with but a fraction of her intelligence. I have our father’s height and amber-flecked brown eyes, but none of his grace, strength, or athleticism. Yet, somehow you see in me the face of an angel.

In you I see the sharp mind and steady hands of a scientist. A fearless tenacious spirit intent on exploring all possibilities even at great cost, able to articulate your ideas, to change hearts and minds. You have boundless strength, so much so that you have been the central support for Mother and me since Father’s death. There is nothing plain about you, little sister, nothing wanting.

How is it that our perceptions have never aligned?

Be right back. GalactiPol is hailing me…

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

To: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

Date: 2161-01-12

Sorry it has taken me so long to return to this letter, but I had a few calls to make. Officers Gavalia and Ambrose boarded my ship at 2315 and took me into custody. My detainment cell is surprisingly modish, with full amenities including a computer and personal uncensored communication device. I have even been given unrestricted access to their onboard digital library.

According to officer Gavalia, though entry into GalactiPol requires extensive training and a stringent vetting system, they have little opportunity to actually do the type of policing their organization exists to perform. I suppose there just aren’t that many galactic criminals to catch these days, besides you and me, that is.

Now where was I? Ah yes. Perceptions.

I’ve been mesmerized by the images you sent of the garbatrite homes, the bright multilayered encrusted structures in every shade of red, orange and pink, lambent lights beneath the gaze of the sun. They expound beauty and ingenuity and life and more than anything, a prescience greater than anything either of us could have conceived.

We’ve been darting back and forth through this solar system, in an effort to outdo one another, trying our damndest to affect the change of our choosing, thinking we are so smart and so in control, when in truth, we are no greater than those garbatrites, and perhaps we are even less wise than they.

Perhaps there is a way for us both to have what we wanted, to terraform Mars and to protect the garbatrites. They were always keen to share their world with us and seeing the ingenuity and beauty of their structures, perhaps we can convince them to help us transform the barren surface of Mars into one of cooperative beauty. We can provide the framework for our cities and homes, and they can build upon them, layering their coral-like exoteric structures, creating homes befitting us all, unlike anything in the entire solar system.

I called Tariq shortly after my detainment aboard the GalactiPol cruiser. Before you think me hopeless, let me explain. Besides being happily ensconced in a polyamorous relationship with two of the nicest men and woman I have ever met, he has long since given up on his art (he was never very good anyway) and has been the Chief GalactiPol Officer for several years. I was hoping that there was still enough lingering affection between us that he would agree to assist me in this difficult situation.

Unfortunately, he is unable, as I had hoped, to have the charges against us repealed, but we have been allowed to serve the entirety of our sentence on Mars. Together.

Shall we do this, sister? Shall we make our dreams come true?

I envision us making a home from our old pod quarters. Perhaps we can build on an extra room and invite Mother. We can even build a special corral for Bobo and Cow, where they can play happily and where they won’t be able to disturb you as you work on your next great experiment. With the help of the garbatrites we can build a greenhouse. We’ll grow corn and tomatoes in soil fertilized with the ashes of our father. We will create a real home, a life. And we will relearn one another, our strengths and weakness, our mutual love for each other. One day other Earthers will join us on our red planet and find a world of wonder encased in garbatrite domes. A home.

Can you see it, sister? Good. Now hold that thought in your mind until we are reunited.

With all my love,

Ziza

*

From: Alamieyeseigha, Anita

To: Alamieyeseigha, Ziza

Date: 2161-01-13

Dear Ziza,

Why did the sisters cross the solar system? To get to the other’s side.

See you soon,

Anita

© 2017 by Rachael K. Jones and Khaalidah Muhammad-Ali

Author’s Note (Khaalidah): When I met Rachael about three years ago, I experienced an instant and sincere affection for her. We toyed with the idea of a collaboration for awhile before we finally dove in. We didn’t outline this story beforehand and had no clear idea where it would go. It took us across the galaxy, with great food, adventure, and lots of laughter. Collaborating with someone as talented and easy-going as Rachael was a joy for me. She charged my imagination. I am pleased to be able to share the results with everyone else. In many ways the end result reflects how I feel about Rachael. She is a sister in my heart and a dear friend.

Author’s Note (Rachael): Khaalidah is my dear friend, my comrade-in-arms, probably a time traveler, and everything I want to be when I grow up. So when we started kicking around the idea of doing a collaboration, I jumped on the opportunity. Writing this story with her was immensely fun, often hilarious, and always surprising. While working on “Regarding the Robot Raccoons,” we eventually realized that although we each controlled a single character’s voice, we were actually writing each other’s characters via our reactions to one another, creating a more complex and nuanced view of Anita and Ziza that you get through just one perspective. I think this phenomenon also exists in all good friendships: in seeing yourself reflected through another’s eyes, you’re inspired to push harder, reach higher, and go farther in life than you ever would on your own. Khaalidah’s friendship makes me a better person, just as collaborating with her makes me a better writer. I hope our readers, in turn, will enjoy the results.

Rachael K. Jones grew up in various cities across Europe and North America, picked up (and mostly forgot) six languages, and acquired several degrees in the arts and sciences. Now she writes speculative fiction in Athens, Georgia. Contrary to the rumors, she is probably not a secret android. Rachael’s fiction has appeared in dozens of venues, including Lightspeed, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Strange Horizons, and PodCastle. Follow her on Twitter @RachaelKJones.

Rachael K. Jones grew up in various cities across Europe and North America, picked up (and mostly forgot) six languages, and acquired several degrees in the arts and sciences. Now she writes speculative fiction in Athens, Georgia. Contrary to the rumors, she is probably not a secret android. Rachael’s fiction has appeared in dozens of venues, including Lightspeed, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Strange Horizons, and PodCastle. Follow her on Twitter @RachaelKJones.

Khaalidah Muhammad-Ali lives in Houston, Texas, with her husband and three children. By day she works as a breast oncology nurse. At all other times she juggles, none too successfully, writing, reading, gaming, and gardening. She has written one novel entitled An Unproductive Woman available on Amazon. She has also been published at Escape Pod , Strange Horizons, and Fiyah!. Khaalidah is also co-editor at Podcastle.org where she is on a mission to encourage more women to submit fantasy stories. Of her alter ego, K from the planet Vega, it is rumored that she owns a time machine and knows the secret to immortality.

Khaalidah Muhammad-Ali lives in Houston, Texas, with her husband and three children. By day she works as a breast oncology nurse. At all other times she juggles, none too successfully, writing, reading, gaming, and gardening. She has written one novel entitled An Unproductive Woman available on Amazon. She has also been published at Escape Pod , Strange Horizons, and Fiyah!. Khaalidah is also co-editor at Podcastle.org where she is on a mission to encourage more women to submit fantasy stories. Of her alter ego, K from the planet Vega, it is rumored that she owns a time machine and knows the secret to immortality.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

WM is the author of a surreal fiction chapbook, Kennel-born, out from Thirty West in the summer of 2018. His work has popped out here and there in Litro, Geometry, AntipodeanSF, and elsewhere. Drop him a line @WillemMyra

WM is the author of a surreal fiction chapbook, Kennel-born, out from Thirty West in the summer of 2018. His work has popped out here and there in Litro, Geometry, AntipodeanSF, and elsewhere. Drop him a line @WillemMyra

The Handmaid’s Tale is a near future dystopia published in 1985 about a United States of America that has become an oppressive theocracy. ((It has also very recently become a TV series streaming on Hulu, but I haven’t seen the show so I don’t have an opinion one way or the other about that)

The Handmaid’s Tale is a near future dystopia published in 1985 about a United States of America that has become an oppressive theocracy. ((It has also very recently become a TV series streaming on Hulu, but I haven’t seen the show so I don’t have an opinion one way or the other about that) Rachael K. Jones grew up in various cities across Europe and North America, picked up (and mostly forgot) six languages, and acquired several degrees in the arts and sciences. Now she writes speculative fiction in Athens, Georgia. Contrary to the rumors, she is probably not a secret android. Rachael’s fiction has appeared in dozens of venues, including Lightspeed, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Strange Horizons, and PodCastle. Follow her on Twitter @RachaelKJones.

Rachael K. Jones grew up in various cities across Europe and North America, picked up (and mostly forgot) six languages, and acquired several degrees in the arts and sciences. Now she writes speculative fiction in Athens, Georgia. Contrary to the rumors, she is probably not a secret android. Rachael’s fiction has appeared in dozens of venues, including Lightspeed, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Strange Horizons, and PodCastle. Follow her on Twitter @RachaelKJones. Khaalidah Muhammad-Ali lives in Houston, Texas, with her husband and three children. By day she works as a breast oncology nurse. At all other times she juggles, none too successfully, writing, reading, gaming, and gardening. She has written one novel entitled An Unproductive Woman available on Amazon. She has also been published at Escape Pod , Strange Horizons, and Fiyah!. Khaalidah is also co-editor at Podcastle.org where she is on a mission to encourage more women to submit fantasy stories. Of her alter ego, K from the planet Vega, it is rumored that she owns a time machine and knows the secret to immortality.

Khaalidah Muhammad-Ali lives in Houston, Texas, with her husband and three children. By day she works as a breast oncology nurse. At all other times she juggles, none too successfully, writing, reading, gaming, and gardening. She has written one novel entitled An Unproductive Woman available on Amazon. She has also been published at Escape Pod , Strange Horizons, and Fiyah!. Khaalidah is also co-editor at Podcastle.org where she is on a mission to encourage more women to submit fantasy stories. Of her alter ego, K from the planet Vega, it is rumored that she owns a time machine and knows the secret to immortality.

Paul Starkey lives in Nottingham, England, but has no information regarding the whereabouts of Robin Hood. He’s wanted to be a writer since he was ten years old, but didn’t really start writing seriously until he hit his thirties. Since then he’s been making up for lost time. He’s had stories published in the UK, USA and Australia, including being published by Ticonderoga publications, Alchemy Press, Fox Spirit and the British Fantasy Society journal. In November 2015 his novella ‘The Lazarus Conundrum’ (a zombie story with a twist) was published by Abaddon Books. He’s also self-published several novels.

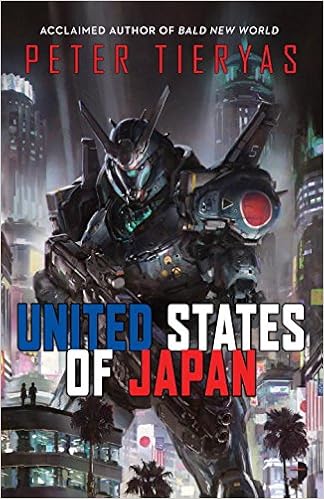

Paul Starkey lives in Nottingham, England, but has no information regarding the whereabouts of Robin Hood. He’s wanted to be a writer since he was ten years old, but didn’t really start writing seriously until he hit his thirties. Since then he’s been making up for lost time. He’s had stories published in the UK, USA and Australia, including being published by Ticonderoga publications, Alchemy Press, Fox Spirit and the British Fantasy Society journal. In November 2015 his novella ‘The Lazarus Conundrum’ (a zombie story with a twist) was published by Abaddon Books. He’s also self-published several novels. World War II is over, decisively ended when the Empire of Japan unleashes their new superweapon on the United States of America. Soon they USA is declared the United States of Japan, under the rule of the Emperor.

World War II is over, decisively ended when the Empire of Japan unleashes their new superweapon on the United States of America. Soon they USA is declared the United States of Japan, under the rule of the Emperor.

Aftermath is a Star Wars franchise tie-in novel written by Chuck Wendig and published in September 2015 by Del Rey. Since Disney decided to declare all of the pre-2014 novelizations as a separate timeline from The Force Awakens movie in 2015, Aftermath is one of the few novels in the official movie canon.

Aftermath is a Star Wars franchise tie-in novel written by Chuck Wendig and published in September 2015 by Del Rey. Since Disney decided to declare all of the pre-2014 novelizations as a separate timeline from The Force Awakens movie in 2015, Aftermath is one of the few novels in the official movie canon.