Dear valued McFleshy’s patrons,

On this, the solemn 50th anniversary of the Vegan Apocalypse, we’d like to thank you — our loyal Consumers-of-the-McFlesh™ — for relying on McFleshy’s (and only on McFleshy’s) for all your dietary needs. As you know, without your loyal patronage our tremendous planet would have surely long since fallen prey (yet again) to the Vegans. Instead, thanks to your fortitude — we’re still here. And thanks to us (and the delicious McFlesh™) — you are too!

For it is only together by consuming at least three juicy Fleshies™ a day, that we can be certain to avoid the fate of our Beloved Billion™ — keeping the Earth safe for all our children…and all our children’s children – etc.

We know this. And we know that you know it too:

“McFleshy’s means survival!”™

McFleshy’s also understands, however, that some of you — too young to have witnessed the Vegan Apocalypse firsthand — have begun to ask troubling questions like: “Why?”

• Why must we consume the McFlesh™ (and only the McFlesh™)?

• Why must we devote so many tens of millions of acres of precious above-sea-level topography to beef, pork, and horse production?

• Why do the Crazy Ones claim that we are the cause of the Great Flooding, the average life-span of forty-two, the balmy winters in Canada, and, of course, Brown River Stench?

As though these were not the Natural Order™ in our Post-Vegan world!

McFleshy’s knows such dangerous murmurings are nonsense…but this is not enough; you must know it too. Yet many malignant myths keep popping up – like fungi – in the minds of today’s youth. And just like that often-poisonous gateway protein, we must eradicate such mental spores before they lead us down the slippery slope to soybean – and annihilation.

It is in this spirit that we hereby set the record straight on this, the solemn 50th anniversary of the Vegan Apocalypse, upon this complimentary maple-glazed, pressed-pork parchment (the text and flesh of which you do hereby agree to consume immediately and in totality after reading under penalty of…etc.).

Thank you again for your McPatronage™!

1. A Clarification of Terms: on vegan vs. Vegan

Today, even 50 long years after our Beloved Billion™ were torn away from us, there are still those among you who hold to the falsehood that there is a distinction to be drawn between a capital “V” and a lowercase “v” as applied to the suffix “-egan.” But the hard reality is:

THERE IS NOT.

At least not in terms of culpability.

FACT: Those humans who embraced the death-cult known as “veganism” are every bit as much to blame for the fate of our Beloved Billion™ as the Vegans.

LET US REPEAT: Both vegans and Vegans are equally to blame for the fate of our Beloved Billion™ — anyone who insists otherwise is a Crazy One.

2. Etymology and Origins

It is still important, however, to clarify the distinct yet interconnected roles these two groups played in the Vegan Apocalypse. And for this, we must revisit the origins of both little “v” and big “V” – to see how their phonetic overlap was anything but random.

a. The cult of veganism

It was in 1944AD, during the height of the Second World War, when an alleged Homo sapiens named Donald Watson coined the term “vegan” – as an abbreviation of “vegetarian.” Promoting an even more radical form of the perverse anti-flesh ideology championed by Adolph Hitler, “The Vegan (sic) Society” formed by Mr. Watson demanded the elimination of not only animal flesh from the human diet, but all animal-based proteins. Followers of “veganism” insisted this diet would prove highly beneficial to both body and spirit, as well as to the environment…

Oh how the Vegans must have been laughing at us, 25 light-years away!

b. Vega/Alpha Lyrae

As for those other Vegans…12,000 years before veganism took wicked root here on Earth, the brightest star in our Northern Hemisphere was the star Vega, in the constellation Lyra.

Appearing in the night sky of today as a blue-tinged white prick of light with a declination of 38-47 and an apparent magnitude of 0.03, the Vegan System is now also known to possess a single earth-like planet that we call Vega-1.

(Obviously we cannot print its more popular name here, as McFleshy’s is a family establishment).

Now you may ask, what else has Vega been called by us humans?

Well, in both ancient Egypt and ancient India, Vega was known simply as:

“The Vulture.”

Just as telling is the name that the ancient Assyrians assigned to it:

“The Judge of Heaven.”

Meanwhile, our own designation of Vega – as Vega – actually comes from the Arabic phrase an-nasr al-wāqi, meaning (again):

“The descending bird of prey.”

And so an undeniable pattern crystallizes into view:

Whether hunter or scavenger, judge or executioner, human stargazers have long intuited some dark truth about our celestial neighbor, winking at us from a mere 25 light years away…

Just ask the Quixotipl Tribe of 12th century Peru.

Oh wait, you can’t…

The Vegans ate them.

3. On “Synch,” or: “As above, so below.”

Now, to fully understand the connection between Vegan and vegan, one must first recall how human vegans behaved – specifically, what a demoralizing experience it was to eat of the tasty flesh in their vicinity.

For those of you not old enough to remember, let this quote from one of Pre-VA America’s greatest voices be your guide:

“With the narrowed eyes of a harridan and the high and mighty tones of a hypocrite…they let loose upon you a litany of falsities, until appetite herself has not one inch of space to breathe free. Yes, my brothers and sisters, to eat of the delicious flesh near a vegan…is to be circled overhead by a vulture readying to descend.”

-Martin Luther King Jr.

(Source: Facebook™)

Let us also consider for a moment what was lost when the supposed-Mr. Watson removed the letters “E-T-A-R-I,” from VEG[ETARI]AN. Some of you may assume this change was inconsequential, but it was anything but; rearrange the missing letters and we find an immediate clue to their meaning:

T-E-R-A-I.

AKA: the Latin word for: “Earth.”

Rearrange them again and we get:

“E-A-R-T-I”

Only one alphabetic unit away from “Earth” in English (again).

Now you see, don’t you??

By removing these five letters, vegans and Vegans were brazenly announcing their unholy alliance and ultimate goal – to take out Earth! At this point, to call the phonetic overlap mere coincidence is to deny the obvious: that vegans and Vegans were linked from the start, in the same interpsychic web of reality-manipulation they would later use in concert with one other – to ensnare our Beloved Billion™.

And what do our McFleshy Scientists call these manipulations of reality?

“Synch™”

For if the Vegan Apocalypse has taught us anything, it is that alien mind penetration can and will cause a toxic run-off of strangely interconnected coincidences (linguistic, logistical, and otherwise) in one’s vicinity.

This is why the last months of our Beloved Billion™ were spattered with such a perverse abundance of what vegans called “signs and miracles”…and our McFleshy Scientists now call “mind-bait and psycho-spam.”

AKA: Synch™

4. Historical Context

These days, it is a challenge for young people to imagine what our planet was like prior to the Vegan Apocalypse. Many of our oldest citizens have contributed to this confusion by characterizing the years pre-VA as a simpler, more innocent time: lower sea-levels, cleaner waters, fewer colostomy bags…

But this nostalgia, sadly, is misguided.

In truth, it was in the deceptive calm of 2012AD-2022AD that the seeds of our Beloved Billion’s™ destruction were being planted. So we must now look back – with eyes tinted-not – to reconstruct how we missed the many signs of impending catastrophe. Only thus may we ensure that NOTHING ALIEN EVER CATCHES US OFF-GUARD AGAIN.

a. The Fate of the Quixotipl (2012AD)

We begin ten years prior to the Vegan Apocalypse, in 2012AD, as a great upsurge of interest in the ancient Mayan calendar reached its zenith.

This archaic time-keeping system was just then concluding an epochal cycle, and many in the New Age spirituality movement (a hot bed of vegan activity) were predicting that the world was about to end as a result – not violently, but in some nebulous sociological transformation often described as:

“Crunchy.”

That same year, archeologists in Peru discovered the remnants of the tiny civilization of Quixotipl, whose own astronomically-calibrated calendar was also set to conclude a cycle – ten years later, in 2022AD.

A series of Quixotipl wall glyphs depicting the last time a Quixotipl Age ended (in 1101AD) was discovered as well; in these, the star Vega is depicted as a gaping maw from which a spiraling vortex of sharp-beaked “bird men” are swooping down to Earth…to carry the Quixotipl people away…

Ironically, those excavating the Quixotipl site at first believed its inhabitant to have been a decent, flesh-eating folk– on account of the thousands of hastily discarded bones found at the top layer of the dig. As soon as the archeologists realized these unburied, unburnt skeletons (all carbon-dated to the 12th Century AD) belonged to men, women, and children, however…they changed their tune.

The Quixotipl, it turned out…held to an entirely flesh-free diet.

b. The Blowing Winds of Vega (2012AD-2016AD)

To understand what destroyed the Quixotipl people over one thousand years earlier, we must next look to the disturbing transformation of Stephan Mallik, aka: “Starfalcon” – once a mild-mannered PhD student in the archeology department of the University of Virginia…now a footnote in history – right alongside Benedict Arnold.

After conducting extensive field research on the Quixotipl site in 2012AD and again in 2013AD, Mr. Mallik’s scholarship helped popularize the theory that the Quixotipl had died in a mass ritual suicide – just as the last cycle of their calendar was concluding. Mr. Mallik explained the absence of sacrificial relics at the site (e.g. blades and chalices) by proposing a slow-acting poison ingested away from their final resting place as agent.

Many archeologists praised this hypothesis.

But then, in 2014AD, just as Mr. Mallik was completing his dissertation on the subject, he began to behave erratically. “What if there IS a deeper cosmic order embedded in The Calendar?? Now that I’ve eliminated ALL meat and dairy from my diet, there are so many ENERGIES I’ve grown attuned to…forces I never imagined possible before…”

(Source: Reddit.com/r/vegan [defunct])

Thus began one of the first internet posts attributed to Mr. Mallik under the pseudonym “Starfalcon,” and thus – like Saul of Tarsus – did Mr. Mallik discover his “calling” as both apostle and evangelist for Vega.

(Of course, unlike Christianity, the so-called “Gospel of Vega” had a dark side!)

According to Starfalcon – and his dozens of disciples – only those who cleansed themselves of the tasty flesh would ascend to the “next level” of human evolution. This Grand Shift was set to correspond with the next turn-over in the Quixotipl calendar– in 2022AD – in communion with the “enlightened” beings of Vega-1.

Apparently, the more ancient alien civilization had been guiding humanity towards veganism (and “salvation”) for millennia…

The acolytes of this radical, esoteric strain of veganism converted many poor bodies throughout the 2010’s by tapping into the irrational hodge-podge of mytho-mystical belief still plaguing humanity at the time: utopian fever-dreams, socialist messiahs, drug-fueled raptures, quantum physics, sweaty yoga, string theory, artificial intelligence, and the false-promise of singularity…they even identified the children’s novelist Arthur C. Clarke as a Vegan prophet, claiming he had encoded many of his adolescent fictions with “messages” for true believers.

Many thousands would perish as a result of such nonsense.

Of course, this death count was just a drop in the ocean – a trifle, really – when compared with the seeds of mass slaughter that the “respectable” vegan community was planting, concurrently, in the secular, “more rational” worlds of academia, business, and politics…

Here we discover the true depths of vegan treachery!

c. The Anti-Flesh Crusade (2017AD-2020AD)

Today, thanks to the tireless research of our Scientists here at McFleshy’s, we can affirm with 100.00% certainty that both Global Warming and Brown River Stench were ALWAYS inevitable — historically and geologically.

That’s right: no matter what we as a species did or did not do to prevent them, they WERE coming for us.

LET US REPEAT: the rising tides in Ohio and Nevada are NOT our fault.

It’s a McFact™.

So how then to explain the obsessive efforts of the Environmental Lobby of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries AD to prevent the unpreventable?

Two words: “vegan infiltration”

Using the Sword of Damocles of “Climate Change” to instill fear and panic, vegan infiltrators pointed their crooked fingers at the embryonic meat industry, trumping up ridiculous charges of causality between then meager modes of tasty flesh production and incipient global warming. For instance: they claimed that methane gas emissions from livestock were heating up the Earth’s atmosphere.

Just imagine that for a moment, would you…?

Farts!!

They also claimed that the removal of millions of acres of swelteringly hot jungle and rain forest– to make room for much breezier grazing pastures – was making Earth hotter too. Looking back, the vegan infiltrators’ accusations appear backward, irrational, and unscientific – of course. At the time though, many were desperate to believe there would be some way to avoid the onslaught of Brown River Stench. And who can blame them?

Sadly, the notion that Homo sapiens had a choice in this matter is hubris.

Or as we like to call it: McHubris™

The truth is, we humans have the tendency to believe whatever supports our preconceived worldviews…and many good-intentioned environmentalists were turned against the Great Meat Makers as a result of these untruths.

Everywhere one looked, vegan distortions were sweeping into the collective consciousness, not just through the Environmental Lobby, but through the worlds of business and healthcare, in the ideologically corrupt productions of Hollywood and academia – even through children’s television!

Yes, everywhere they could, the vegans waged their deadly war:

• At major universities, they wrote venomous screeds on the “human rights” of animals. (Just think about that for a moment!)

• Student unions promoting radical anti-flesh lifestyles soon became entrenched. (Mass protests and boycotting against the meat industry followed in abundance.)

• Meanwhile, in science and medicine, vegan propagandists paid off corrupt “experts” to assert that flesh-consumption levels in impoverished nations (like Mexico and Africa) were healthier than those in the one exemplary flesh-eating nation in the world: The United States of America. (Fortunately, most Western doctors ignored such findings.)

• Unfortunately, in food manufacturing, vegan “entrepreneurs” began churning out an endless supply of flesh-substitutes, from oft-carcinogenic sources like soybean, pea protein, and the aptly named seitan.

And so it was that the developing world remained nearly fleshless, while in first-world kitchens, kale and squash proliferated.

In other words: at the very moment when humanity NEEDED to be manufacturing as many gross tons of cow and horse protein as possible, we were instead flapping about with our pants around our ankles.

Until finally…the stage (and table) for the Vegan feast…was set.

d. The Rising Horror (2021AD)

Imagine if you will…a morning like any other…

You replace your Clara-Lung Breathing App™ with a fresh mask, report any dissonant dreams you may have had to our McFleshy-Care™ “We Care!” Reps, punch your request for AM-McSustenance™ into your breakfast console, and begin to serve your toddler its delicious McFleshy Baby Slur™ (so that it may grow up big and loyal). Only this time, for the first time ever, your precious babe turns its mouth from the McSpork™ – refusing to consume even one bite!

Of course, you know your child needs to be ingesting at least three iron-rich gelatinous cubes of Slur™ per meal to be truly safe from Vegan mind-rape. Yet for some reason, on this terrible morning…your precious one will NOT submit.

“No, mommy,” it cries. “No, daddy!”

“But this Slur™ is packed with the same McFleshy-Blend™ of 743 tastes and flavors that you adore so very, very much,” you assure your stubborn child. “You LOVE consuming your delicious McFleshy’s Baby Slur™! Whatever has gotten into you, toddler!? Why don’t you EAT IT already?! Are you turning into one of THEM?? ARE YOU?!”

But it’s to no avail; your baby will not eat its Slur™.

Now…if you can imagine such a nightmarish ordeal, you should likewise be equipped to envisage the UTTER HORROR facing so many billions back in 2021AD, as they watched mothers, fathers, siblings, and children…begin to slip away from them…by refusing the precious flesh.

Of course, the first signs of Vegan mind-infection were considered by some to be minor, even pleasant…

In addition to low-grade Synch™, many of The Affected™ reported strange dreams…of remarkable vividness and power, uniformly alike in content.

Here is how one notable victim described the experience:

“I found myself soaring bodiless…across multiple otherworldly landscapes at once…yet feeling no sense of fragmentation or even disorientation in the process. Only pure, transcendent bliss…”

-George W. Bush Jr.

(Source: The New York Times, 2/14/21)

Indeed, the Affected™ universally reported feeling embraced in their dreams by some vast intelligence, which they (somehow) felt both a part of, as well as separate from, throughout…

Soon—

• Affected™ politicians were retiring from public life in droves –with hauntingly authentic farewell speeches.

• Affected™ painters were painting images so sublime that art galleries had to start stocking tissue boxes.

• Affected™ poets were composing verse so sensitive to the depths of The Human Condition™, that several poetry books almost cracked a Best Seller List.

• Etc.

Yes, for one brief shining stretch of months in early 2021AD, even the most skeptical of flesh-eater could be excused for wondering…if maybe, just maybe there was something to this supposed Gospel of Vega after all…

e. The Saviors of the Flesh (2023AD – HAPPILY EVER AFTER)

Of course, we don’t want to re-traumatize you with the gory details of 2022AD:

• You know all about the terrifying intensifying of Synch™ and the psychological withdrawal of the Affected™ that followed already.

• You have heard – again and again – the audio recordings of their endless chanting…in that hideous alien tongue.

• You know too well what an eruption of Bright-Light-Madness looks like…as well as the ugliness of what follows…

• That is, Epilectic-Death-Syndrome (AKA: “the Vegan Slurp”).

• And of course, your brain is thoroughly seared with the millions of Instagram images of the Tragic Flesh Heaps™ – emptied of all that once made our Beloved Billion™ human. (For the record: our Beloved Billion ™ never included the deaths of self-identifying vegans – who numbered around 600,000,000, and were usually the first to go. All we can say of their flesh…is good riddance.)

Fortunately, you also know the happy ending to this story…

• How the corporate leadership of The Great Meat Makers™ banded together, forgoing profit, reward, and even vacation days – to rapidly ramp up production and distribution.

• How the brave Sizzle Queen, Fry Factor, Chateau Du Burger, Taco Americano, Veal Deal, Nugget Town, and Roasties corporations (to name but a few Heroes of the Flesh™) gave us the Force-Feed Initiative™, which spared so many millions on the brink.

• How these brave corporate entities mobilized the armies of Blackwater, Iron Eagle, et al to overthrow the political leadership of the day, installing us as Global Hegemonic Potentate For-All-Time™ (AKA: GHP-FAT).

• And how, finally, you helped rename us “McFleshy’s” after this bold public choice beat out write-in candidate: “SukDeezNutsVega!” in online polls, three years later.

After all, as we like to say here at McFleshy’s:

“Here at McFleshy’s, you get…HERD!”™

5. Winners and Losers

As we all know, it is a truism of human history that it is written by the winners…

Yet sadly, there are no winners in the intergalactic struggle we are currently waging on your behalf – at least not yet. And so this history of the Vegan Apocalypse must remain incomplete, even after 50 years of healing, rebuilding, and all-you-can eat March McRibble Madness!™

Yes, it is true that the vultures of Vega, along with their flock of human sheep, took us by surprise once. But now WE KNOW. And now that we DO KNOW, there is simply no excuse to ever deviate from the tasty flesh again.

Yet, even after all we’ve been through together, all the tasty flesh we’ve provided you and yours, there are still those among you who refuse to accept the Natural Order™. There are even those among you who are STILL trying to summon them back…

We speak, of course, of the Crazy Ones, those who forego the delicious McFlesh™ for whatever desperate scraps of fungus and algae they can summon into being – in hidden bathtubs and root cellars beyond the security-ensuring gaze of our benevolent McWatch™ lenses.

Yes, these maniacs would actually summon the Vegans BACK into our world!

• LAMENTING their absence from our mental airwaves!

• PRAYING for their immediate return!

• BLAMING McFleshy’s for clotting the arteries of consciousness so that the Vegan Mass-Mind simply cannot penetrate!!

As to that last accusation, all we can say is: HECK YEAH!

After all, history IS written by the winners!

And this war is one we can – AND MUST – win!

So please, if you do know of any Crazy Ones in your midst…sneaking a carrot here, whispering doubts about McFleshy’s there…report them to us IMMEDIATELY; we MUST quarantine ourselves against THEM.

So thank you once again for your ceaseless and unquestioning McPatronage™.

Now eat up! Chewing and swallowing every last bite of the complementary maple-glazed pressed-pork parchment upon which this unquestionable record of the Vegan Apocalypse has been printed – as prescribed by McFleshy International Law™.

We do so appreciate your cooperation and loyalty…

After all, this story won’t swallow itself 🙂

© 2018 by Benjamin Friedman

Author’s note: The germinal seed for “The Vegan Apocalypse: 50 Years Later” came to me back in 2011, during the height of fascination with the Mayan calendar and its impending terminus in 2012. At the time, I was working at a Yoga center in Massachusetts called Kripalu, where the thought of a collective shift in culture and consciousness was not just a laughable bit of New Age naivete, but a genuine and sincere hope for resurgent 60’s-style idealism. And with the Occupy Movement and Arab Spring then at their zeniths, it was true; anything seemed possible. Of course, as in George Lucas trilogies, so in historical dialectics…as the various “empires” of cynicism, despotism, corporatism, and the politics of propaganda and deception have all since “struck back” in myriad and disturbing ways. This story was my way of grappling with that great gulf between human possibility and reality. For just as the Mayan Calendar wasn’t the end of history for the good, the Vegan Apocalypse of my story isn’t meant to be seen as the end of all hope – just another chapter that depends on human agency for its sequel.

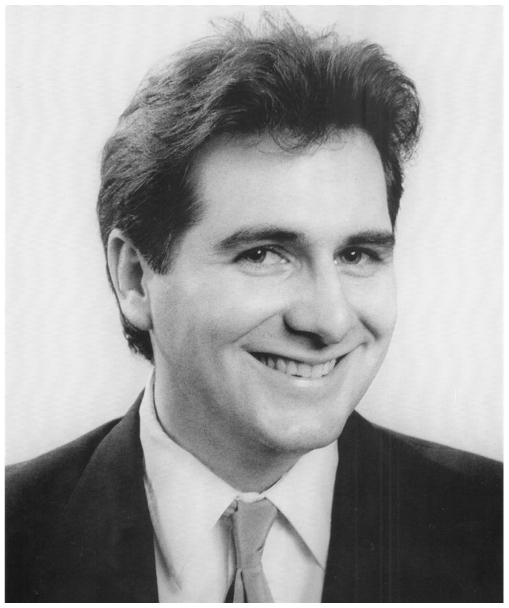

This is Ben Friedman’s first sale to an SFWA-accredited publication, an honor for which he is titillated to an almost obscene degree. Previous stories of his have landed at 365 Tomorrows, Every Day Fiction, The Story Shack, and Sonic Boom Literary Magazine, and his screenwriting has won the Golden Blaster Award at the Irish National Science Fiction Film Festival as well as the Grand Prize from the WeScreenplay Short Film Fund Competition. He currently is recovering from an inauspicious injury (that could be the punchline to a bawdy joke were it not oh-so-true) in his hometown of South Orange, New Jersey after a number of years of peripatetic soul-seeking throughout New England, Colorado, California, Israel, and Australia.

This is Ben Friedman’s first sale to an SFWA-accredited publication, an honor for which he is titillated to an almost obscene degree. Previous stories of his have landed at 365 Tomorrows, Every Day Fiction, The Story Shack, and Sonic Boom Literary Magazine, and his screenwriting has won the Golden Blaster Award at the Irish National Science Fiction Film Festival as well as the Grand Prize from the WeScreenplay Short Film Fund Competition. He currently is recovering from an inauspicious injury (that could be the punchline to a bawdy joke were it not oh-so-true) in his hometown of South Orange, New Jersey after a number of years of peripatetic soul-seeking throughout New England, Colorado, California, Israel, and Australia.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

Matthew Claxton is a reporter living near Vancouver, British Columbia. His stories have appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction, Mothership Zeta, and The Year’s Best Science Fiction 34. Rumours that he is three small dinosaurs standing on each other’s shoulders in a trenchcoat have never been proven. You can follow him on Twitter @ouranosaurus.

Matthew Claxton is a reporter living near Vancouver, British Columbia. His stories have appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction, Mothership Zeta, and The Year’s Best Science Fiction 34. Rumours that he is three small dinosaurs standing on each other’s shoulders in a trenchcoat have never been proven. You can follow him on Twitter @ouranosaurus.

The Handmaid’s Tale is a near future dystopia published in 1985 about a United States of America that has become an oppressive theocracy. ((It has also very recently become a TV series streaming on Hulu, but I haven’t seen the show so I don’t have an opinion one way or the other about that)

The Handmaid’s Tale is a near future dystopia published in 1985 about a United States of America that has become an oppressive theocracy. ((It has also very recently become a TV series streaming on Hulu, but I haven’t seen the show so I don’t have an opinion one way or the other about that)