edited by Ziv Wities

Jaffa Cakes: 4/10

The Jaffas haven’t aged well. The orange jelly went runny while the box sat trapped in the trunk of that abandoned car sunk in the ditch. A whole ant colony died glorious chocoholic deaths trying to carry them off. There’s all these little antennas sticking out of the cakes. I took a bite so I could rate them, but left the rest alone.

Jordan finished his whole cake, antennas and all. He’ll eat anything.

We’re camping in Retro Games overnight. Jordan needs a new d4 for his dice set, and I want to forage for better snacks. It’s risky—the Ganglies like buildings, and this one’s only one story tall—but we haven’t seen any of them in a few days, so we’re taking the chance.

Anyway, I’m a yellow belt in Taekwondo. Just let them try to eat our bones. I’ll kick them to bits.

*

Gulab Jamun: 8/10

They’re canned donut holes soaked in rosewater syrup. I’ve added “roses” to my Master List of Things I’ve Eaten, after “poodle” and “roaches.” Jordan says stuff from dented cans might be full of bacteria, but the dent was pretty small, and we heard a Gangly scritching against the supermarket doors from our rooftop perch. Figured we might as well die with a sugar high.

The donut holes had mostly dissolved into the syrup, but they tasted so good I almost finished them before I remembered to offer Jordan some.

He rolled his eyes. You’d think he was my actual little brother and not just my pretend one. “You’re gonna be sooooooo sick tomorrow, Nadia,” he said. But he ate them too. I guess dying from bacteria together is better than fleeing Ganglies solo.

We sat on the roof after dinner and watched for Ganglies in the parking lot. Jordan got this huge sack of fancy unicorn dice from Retro Games. Probably a thousand of them, d4 through d100, shiny ivory like polished teeth. We were taking turns chucking them at bullet casings on the sidewalk, trying to see who could get the closest, when Jordan spotted a dust cloud from the street.

Then we were both on our feet, jumping and waving and screaming as a whole convoy rumbled past. We hadn’t seen that many adults in weeks, not since the Ganglies raided the last shelter we’d been in. Big trucks, a couple of tanks, and a semi with the windows covered in steel plates with holes cut in them. Gangly-proofed and then some. The convoy rolled into the parking lot, crushing shopping carts and abandoned bikes. My tummy flipflopped, half from excitement and half from imagining all the snacks those trucks must have. Beef sticks, baked cheese, maybe even BBQ potato chips (I was craving things that start with B).

The lead tank’s hatch popped open, and a lady with a buzz cut and camo pants climbed out. “You kids alright?” she hollered, cutting her eyes toward the pockets of shade near the cart return. Ganglies liked to unfold themselves from shadows when you weren’t looking.

I liked her. She reminded me of Officer Laws, my old middle school security guard.

“We’re orphans,” Jordan said, which was the truth, but also the best thing to lead with if you ever need adults to trust you.

The Camo Lady popped back down into her tank. These days nobody wants to share their food with strangers, but everyone makes exceptions for kids. There aren’t that many of us left, after all. We don’t run as fast as adults. A few minutes later, she came out again. “Can you climb down to us?”

“The store’s clear,” I told her. “We’ve been foraging. I found donut holes. Kinda.”

We gave her a tour of the ruins. I guess she liked what she saw, because she radioed her people, and they all piled out, twenty-one total and not one kid, and began stripping the shelves onto the checkout counters.

It was getting late, but Camo Lady (everyone called her Lily) said we could ride along. So Jordan and I scrammed back to the roof to get his dice and my backpack before we joined them.

I was halfway down the ladder when the Ganglies arrived.

The shadows between the shelves got real, real dark, like a cat’s pupils under the bed. Then out shot a long, thin spiderleg, then half a dozen more, and then whole Ganglies hoisted themselves up from the darkness onto the supermarket floor.

The Ganglies skittered long and tall right over the shelves on those long bony limbs, knocking jars to the ground and slamming shopping carts against the walls. They looked thin even for Ganglies, like if a skeleton married a spider.

Someone fired a gun and a window shattered. People were screaming everywhere, but it was over almost as soon as it started, and the Ganglies were dragging the bodies back down into the shadows. The final Gangly limped toward that shadow-portal more slowly since one leg-joint had been blasted off.

I hated it for killing Lily just when we were about to get protected. I threw a fat white d20 at it. It bounced off the floor and came up natural 20. Critical save. Instead of charging like most Ganglies do, it sat on its haunches and picked up the d20. Not coming after us, not calling for its friends, not scratching claws on the ladder, none of your usual Gangly stuff. Nibbled the d20 and watched us. Then it hooked the dead man again and crawled into the shadows, folding back into wherever they went when we weren’t watching.

I dropped to the floor and did a roundhouse kick at its dragging hind legs, and for just a sec my foot whiffed through the floor into somewhere else, somewhere damp and chilly and not-here. It was silly and dangerous. I braced for a Gangly’s claw jabbing through my shoe, but nothing happened except the shadows closed, and it was just the supermarket, quiet and empty.

At least until all the bodies came back 30 minutes later, minus their bones.

Jordan and I discussed our new D&D swag while we combed the abandoned convoy for food. It gave us something else to think about besides the flat deboned sacks of meat that used to be Lily and her people. “Maybe these dice really are made from unicorn horn,” he said. “Horns are kind of like bones, right? Teeth too. I bet that’s why the Gangly liked them.”

“Unicorns aren’t real, though.”

“That’s what they said about the Ganglies,” said Jordan.

*

Twinkies: 1/10

Threw them up. I’m sick. Jordan’s sicker. Stupid dented donut hole cans.

He didn’t say I told you so. That’s why we’re best friends.

*

Zebra Cakes: 7/10

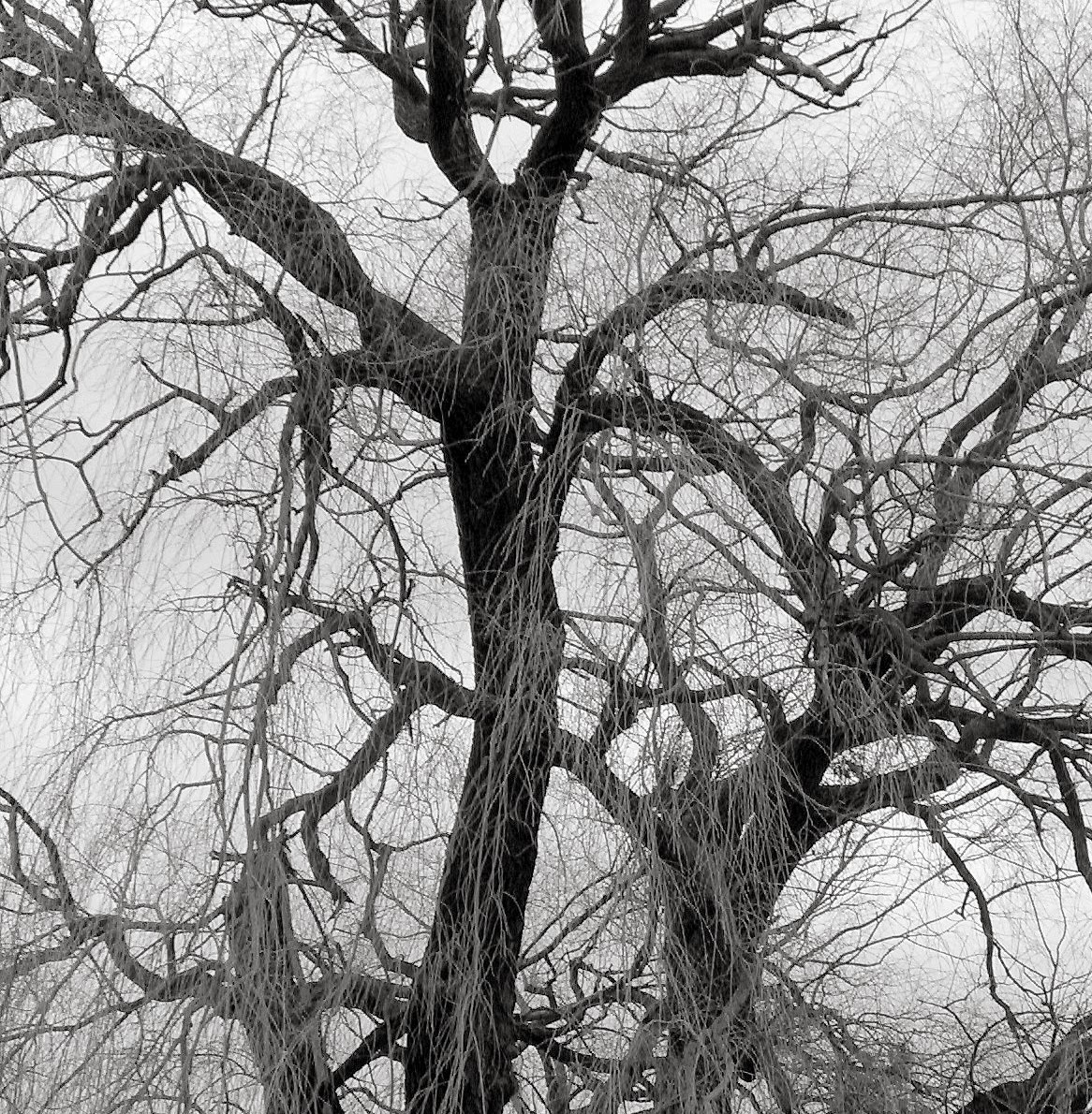

Jordan taught me how to sleep in trees tonight. We found the Zebra Cakes suspended among the branches in a dead pilot’s bag. The box showed a happy cartoon unicorn zebra—zebracorn?—saying, Magical Munchies for One-of-a-Kind Cravings!

The pilot’s mummified skin hung limp and empty inside the flight suit. Not Ganglies this time—all the bones were still there, just a little jumbled up. Ganglies can reach pretty high, but they don’t climb trees.

To sleep in a tree, you tie your hammock between two big branches and let the wind rock you to sleep. We used the dead pilot’s parachute. Jordan and I curled up together like the Zebra Cakes, two in a pack. The cakes had gone stale, but we didn’t care. Everything tastes great when you’re swinging peacefully under starlight with your best friend.

The dead pilot had a dog collar in their bag too, a worn pink one with a brass buckle, tucked in a pouch with some photos and a wallet. I hoped that meant the dog got away safe.

“I had a dog once,” said Jordan. “Back before.” He didn’t usually talk about the days before the Ganglies. “Dogs used to be wolves, you know. Before we tamed them.”

“We should’ve let them stay wolves.” The Ganglies had picked the dogs off pretty quick. Dogs didn’t have the sense to keep quiet and climb trees like people did.

I miss dogs.

I thought about wolf-taming while I lay there stargazing with Jordan warming my back, about cavemen huddled around bright fires to keep the howling wolves away. Except one day a hungry pup scooched close enough for somebody to toss it a bone. You had to tame things a little at a time. First step: don’t kill each other on sight.

After Jordan fell asleep, I licked one of his unicorn horn dice. It didn’t taste like much of anything, but neither do my teeth, and they’re probably made of bone too.

I’ve added “bone” to my Master List of Things I’ve Eaten. I’d take another Zebra Cake over bones any day. But there aren’t going to be anymore Zebra Cakes, are there? Or zebras, for that matter.

Someday zebras will be like unicorns. Nobody will believe they were ever real.

*

Pocky: ??/10

We shouldn’t have slept in the tree. The Ganglies can’t climb, but they can sniff out crumbs. Must have been ten of them down there by morning.

We threw down the dead pilot to distract them. They picked the bones one by one out of his mummified skin like a plastic wrapper.

Wish I hadn’t seen that. It’s all I could think about when I opened the Pocky. They snap in half just like old bones. Chocolate-dipped old bones.

Jordan tore open his shin sliding down the tree once the Ganglies left. I had to sew it up with twisty-tie wire from a bag of moldy hot dog buns. Jordan cried a little. I gave him the whole box of Pocky to make him feel better, which is why I can’t rate them. I hope we don’t have to sprint again soon.

“You ever feel bad for them?” he asked, once he stopped crying.

“The Ganglies? Nah. Bunch of evil aliens. They ate both my moms. I hate them.”

Jordan crunched the chocolate off his Pocky stick. The sound made my teeth itch. “I feel bad for them. My theory is they’re starving. They crashed here with no way home, and nothing but bones to digest. Being hungry sucks. Like, if we went to Candyland, we’d be serial killers, right? The Licorice King and Gumdrop Princess would run screaming from us.”

Stupid Jordan. I want to write about Pocky, but now my Master List of Things I’ve Eaten just makes me feel like a Gangly.

*

Strawberry Twizzlers: 10/10

Okay, Jordan was right. I’d totally eat the Licorice King. Sue me.

*

Pickle in a Bag: 8/10

They have such a good crunch it doesn’t even matter they’ve turned pee-yellow from age. Their mascot is a cartoon pickle with big googly eyes. We ate so many we both smell like librarians now. We needed it after such a close call.

Jordan and I fell in with a minor league baseball team, the Ferndale Razors, while foraging at the old stadium. I thought maybe the stadium would have fried pickles, and I don’t have many things under “P” in my Master List of Things I’ve Eaten, especially after skipping the Pocky.

Instead we came across the Razors’ secret base in the concession stands. They told us they don’t normally show themselves because the Ganglies don’t know to look for them down there, which keeps them safe. But Jordan was crying because his leg hurt, just sat in the bleachers bawling, and they felt so bad for us they made an exception.

See? Everyone makes exceptions for kids.

The players helped us down the bleachers to the lower levels, which wasn’t easy for Jordan, since the elevators were out. The Razors gave Jordan a shot of medicine in his leg, then let us eat whatever we wanted from the concessions stash, which was good because I’ve been tightening my Taekwondo belt a whole lot recently.

“What I don’t get,” said Mr. Aaron, their catcher, in a comfortable drawl, “is how y’all have survived this whole time just the two of you, without proper shelter. The Ganglies track just about anyone not locked down deep these days. It’s why most of us have gone underground.”

“Jordan’s lucky,” I told him, because it’s true. Just yesterday he found a four-leaf clover.

Staying with the Razors was the luckiest thing of all, though. The Razors were strong and smart, and Jordan and I were tired of running. And if we stayed at the stadium, we could have popcorn and donuts forever.

We didn’t have the chance to even try the donuts because the Ganglies attacked that night. The sound of bones getting slurped from bodies just below your bunk bed will wake up anyone. Jordan raced up the ladder and burrowed with me deep under the sheets like the monsters might overlook us if we kept a blanket over our eyes.

That’s how my moms died. Burrowed under the covers while I watched from the closet. Blankets won’t protect you from anything but the cold.

I thought I’d try to help the Razors, or at least make them forget about Jordan. I cinched my yellow belt tight, counted to one hundred Mississippi, and ninja-rolled out of the bunk bed. I threw some punches at the long spindly legs retreating into the dark. One of the Razors—the pitcher, I think—was yelling bloody murder. I grabbed for his arms as a Gangly dragged him by the legs, and for a few seconds I thought we were both going straight into the shadow realm. But I lost my grip and the monster took him.

It was dim, almost dawn I guessed. A Gangly squatted over the dead baseball players, rummaging through the corpses. It fished out a small white skull, popped it into its razor-tooth mouth, and chewed it slowly, like those half-popped kernels you find in the bottom of the bag. You don’t really notice how small a skull is until you see it outside someone’s head.

I was real mad, and figured we were about to die anyway, so I started chucking bagged pickles at it just as hard as I could. “Go away! Get! Begone, you!”

It poised, rocking on mismatched hind legs for a sec. That stumpy walk again! Then it threw a pickle in a bag at me. The package exploded, splashing pickle juice all over my Taekwondo dobok. The pickle slid under a chair, leaving the wrapper empty. Just a cartoon Mr. Pickle staring up at me, flat and boneless. The Gangly folded up into the shadows, and was gone.

Jordan and I stuffed our pockets and bags full of food and went on our way. It sucked to lose all the free donuts, but no way were we living in there with all the bodies. Not when the Ganglies could come back at any moment. Instead we gorged on pickles and hit the road.

If the same Gangly that killed the convoy people also killed the baseball players, maybe there aren’t that many Ganglies after all. But why are they following us? Do they hunt in packs? Did they take a shine to us? Are they waiting for us to ripen like stale candy canes after Christmas?

Sometimes when we bunk down for the night, we find a bagged pickle somewhere neither of us remembers leaving it, right where the shadows are thickest.

I wonder what we taste like to a Gangly.

#

Star Crunches: 0/10

I was crying so hard the Star Crunch just tasted like tears and snot, but it’s all I had in my pocket when I led the Ganglies away from poor hurt Jordan.

We’d stayed up all night playing D&D on the roof of an elementary school, which isn’t the best spot to hide from Ganglies since you can’t clear out all the classrooms. But the nurse’s office has medicine for Jordan’s leg, and the big flood lights keep the shadows away, so we risked it.

How come they keep finding us? How come we’re still alive when everyone else is dead? I miss my moms. I miss my dog. I miss not knowing what people look like on the inside.

I woke up when Star Crunches began pelting my sleeping bag. They arced sideways from over the edge of the building like hail in a windstorm. Some Ganglies down below had one of those rotating metal snack trees you find at gas stations. Our old stumpy-legged friend was working them off and lobbing them at the roof.

Jordan and I lay really quiet underneath a blanket, fending off the snacks, because really, what could you say about that? “They’re just trying to bait us,” I decided. “It’s a new hunting technique.”

“I bet they learned it from you,” said Jordan irritably, “when you threw them my unicorn dice.”

“Seriously, Jordan? No way you’re still mad about the dice.”

“Obviously. You can’t roll initiative with two d10’s. It’s not mathematically correct.”

Jordan’s such a punk, but you should never stay mad at anyone after the apocalypse. He looked really bad, honestly. He’d been getting paler and sweatier ever since we’d left the baseball stadium, and our food had run low. Jordan was already pigging out on Star Crunches.

Then a tree crashed into the rooftop. The Ganglies must’ve worked all night digging it up. They strolled right up the trunk like pirates on a gangplank, all spindly and uneven in the moonlight. So thin and a little wobbly, like when you’re fall-over hungry and can’t even make it to the table.

Maybe they’re not naturally gangly at all.

No way Jordan could run from them, not with his hurt leg. I whooped and hollered at the Ganglies, and bolted toward a spot where trees overhung the roof. “Go for the door, Jordan!”

I caught the sagging branches of an old elm leaning over the roof and climbed up as high as I dared. “Jordan? Jordan, you there?” I hadn’t heard any running, or the rusty door clanging closed. The Ganglies hung thick around the spot where I’d left him.

More Ganglies gathered around my tree. One of them gnawed on something. Maybe a dead deer. The shadow around the roots thickened, and another Gangly climbed out right underneath me. I tossed the second Star Crunch into that shadow, into their dimension, but I missed, and it just glanced off the dirt. I felt just like a Gumdrop Princess in Candyland, begging it to please fill up on something else, please don’t notice Jordan, because I need him and anyway I’m not done with my journal yet.

I was all set to climb down just as soon as my heart stopped racing. Maybe if they ate me, they’d leave Jordan alone. But before I could pick a way down the branches, they unzipped the shadows again and slipped away ahead of the morning.

I ran all over the school looking for Jordan, whispering for him, screaming his name, lying on the rooftop sobbing while the sun dragged all the shadows long and spindly. But I didn’t find him. When I finally ran out of tears, I lay peering at the patch of leaves where the shadows had unzipped, waiting for the return delivery, the one they always made of the… unused bits. I didn’t want to see Jordan like that, all flat and empty without even his skull, but when it’s your best friend, you don’t really have a choice.

I waited all day, but they never sent him back. I’ve been waiting ever since.

Where are you, Jordan? Where did they take you? Are you in the shadow dimension still? They could’ve eaten us a billion times by now, but they always spared us. Are they finally out of adults to eat?

Whatever it is, I’m sick to death of running. I’ve got a plan to get into the shadow dimension. I’m saving Jordan if it kills me. And if he’s already gone? Well. I’d rather be eaten than live without him. There’s a reason they always come two in a pack.

Jordan, if you’re reading this, I’m really really sorry about your unicorn dice.

*

Gummi Bears: 10/10

My moms always used to say there’s good news and there’s bad news—which do you want first? You’re always supposed to ask for the bad news first. So here it is: I could only think of one way to get the Ganglies to open the shadow dimension, and I’m not proud of how I did it.

I had to walk a long time to find some adults. It was nearly a week of searching the outskirts of the city before I found it: the sleepy hum of generators, running water, and twinkling lights at dusk. I traced the sound to a complex of three greenhouses surrounded by a barricade of overturned semi trucks, patrolled by adults with guns.

I waved an empty foil wrapper to get their attention. “Help! Help me! Over here! My parents died, and I’m lost.” I made a big deal out of crying and wiping my grimy face on my Taekwondo uniform, which wasn’t so white anymore, and I slumped my shoulders so I looked really small and pathetic.

That got me brought inside real quick. Everyone makes exceptions for kids.

I liked how they’d Gangly-proofed their home. They’d rigged huge floodlights like from a football stadium all over the whole compound, especially inside the greenhouse. You had to sleep with a mask over your eyes to shut it out, but it kept the shadows away. I had salad for dinner for the first time in who knows how long. I’m adding something called kohlrabi to my Master List of Things I’ve Eaten. It looks kind of like Yoda if he turned into a vegetable.

I pretended to sleep until really late at night, curled up in a sleeping bag in the floodlit greenhouse next to the strawberry bed. When the guards swapped shifts at midnight and the compound got quiet, I crept on my knees to the wall socket and pulled the plug on the lights.

The Ganglies piled in immediately, sixseveneightnine before any of the adults could find the plug. I forced myself to crawl toward the Ganglies. They were coming in from under the snap pea bed. I didn’t even wait for them to get out of the way. I just threw myself between their legs into that blackness.

Which means I hit the ground in the shadow dimension face-first and bashed my nose. I’d landed on a walkway running along a series of pits or compartments open from above, almost like honeycombs. I pinched my fingers to stop the blood flow from my nose. A Gangly stepped over me on the walkway and dumped a pile of small, shiny packages into the nearest pit. Then it lowered itself into the compartment.

The Gangly’s long claws shot every which way, performing a thousand tiny chores: refilling a water bucket, organizing the snacks into a neat basket, and tucking the blankets around the kid who lived in the pit.

And this is where I have good news, because the kid was Jordan.

I made a huge mistake then and yelled his name. I was just so happy I couldn’t keep my voice quiet. A lot of things happened very quickly. The Gangly in the pit whirled around and skittered toward me, stumping on its shortened limb. Jordan tried to stand up, but he fell over. His leg was in a cast now. I realized all at once what horrible danger I was in and spun to find the way out, but other Ganglies were streaming back home, each with a shrieking adult in tow.

The stump-legged Gangly caged me in its limbs, pinning my arms to my side, and dropped me into Jordan’s pit. Hitting the floor didn’t hurt like I expected because all the snacks broke my fall. I kicked away a bag of gummi bears, unopened and undamaged, with that little air bubble inside from some far-off factory before we ever knew about Ganglies.

“Nadia?” Jordan crawled right into my arms. He was shaking so hard I thought his skeleton would shred his body and leave his skin-sack behind. “They got you too. I thought you got away.” He sounded wrung out, like he’d cried all the tears already. He looked good, though. Better color, stronger, even gained some weight. That chilled me, because you don’t have to be a serious brain genius to remember Hansel and Gretel.

“They’re going to eat us,” I said. “They’re saving us for dessert, aren’t they?”

Jordan slowly shook his head. He’d stopped trembling. “No. No, it’s nothing like that.”

My stomach turned in on itself, but you can’t digest fear. “Then what’s the deal?”

Jordan shushed me. “Nadia. Just hush a sec. Listen.”

The Ganglies trooped back from our dimension on the walkway under a dim gray sky that pulsed with red lights. A whole forest of legs, all of them gripping bones and skulls and more snack bags. Salted peanuts, chocolate-covered cherries, fun-sized potato chips. They distributed the treats into the pits, absolute masses of them, so many I wondered if they had a factory of their own. Then I heard it: high-pitched voices, kid voices, talking or crying or yelling bad words. All those honeycomb pits running out into the darkness.

“The kids didn’t get eaten,” I breathed. Jordan nodded, wide-eyed. I dropped to my knees and pulled him into a hug, just to feel him as close and warm as in the hammock that night under the stars. “Jordan. Jordan, what is this place?”

Jordan’s eyes glinted red in the weird light. “Can’t you tell? It’s our kennel.”

I didn’t understand what he meant until the stump-legged Gangly climbed back down into our pit and held out a clawed appendage. A pearly white bone gleamed there. It was one of the unicorn dice. It nudged a pack of gummis toward me. Gummis As Special As You, said the pink bear on the bag. The Gangly lifted a claw and gently, so gently, traced over my skull right through my hair. I’d expected it to be cold like an insect’s, but it was warm and velvety against my cheek. The gentle hand on a kitten’s head as it burrows, shaking, into your lap.

“Watch,” muttered Jordan. “It’s already sent me out once. That’s how I got my cast. You stay out as long as you’re working, but they like to bring you back between runs.”

It drew a pattern on the pit’s wall. The shadows ripped open. It was an asphalt road to a faraway town where the roofs sloped weird and I couldn’t understand the signs. Streetlights lit up every inch of the pavement, driving back the shadows, and beyond that a castle wall patrolled by adults with guns.

And as one type of fear died in my heart, another one replaced it.

“You just have to go through and get the adults to let you in. The Ganglies don’t hurt kids,” Jordan added blandly. “We get plenty to eat. They don’t eat our food anyway, so they just give it all to us.”

I didn’t need his explanation, because I knew the truth in my heart. It had happened a few times already, after all: we starve, we move, we find adults.

And when we eat, so do the Ganglies.

The Gangly handed me the bag of gummi bears. It nudged me toward the portal. Everyone makes exceptions for kids, but dogs have to earn their keep.

“Let’s get out of here, Jordan,” I pleaded. “We’ll find some adults. We’ll tell them what happened. We’ll stay with them. We don’t have to summon the Ganglies.”

“Doesn’t matter what we want,” said Jordan. “Didn’t matter with the Razors. The Ganglies will find us. Just a matter of time. How long did it take them to eat all the dogs, anyway? A year?” His head slumped to his chest. “I’m sick of running, Nadia. I’m tired.”

I opened the bag of gummi bears and shoved one of the green ones between my back teeth. It was tough at first, but the more I chewed, the more it softened and released its sweetness.

Suddenly I wanted to barf. All that gross and nasty junk food only ever filled you up for a while, and then you were hungry again, and you had to keep eating.

Jordan, Jordan, this isn’t what we wanted. We were supposed to grow up, go to high school, learn to drive, get black belts in taekwondo. We were supposed to run, fight, and survive together. Now we’re giving Candyland tours to Ganglies, and I can’t run away because every step I take would be away from you, and you’re all I have left.

But I realized something, Jordan. They don’t know us at all. They never should’ve let us get so close.

We are not pets. We are not the friendly cartoon wolf on a wrapper. We are the real thing. We have teeth and claws, and when we bare our teeth, it is not to smile. It is not just cakes that come in packs, you know.

They want to snack on us? Well, snacks come at a price, Jordan. And we will make them pay.

© 2021 by Rachael K. Jones

4900 words

Rachael K. Jones grew up in various cities across Europe and North America, picked up (and mostly forgot) six languages, and acquired several degrees in the arts and sciences. Now she writes speculative fiction in Portland, Oregon. Her debut novella, Every River Runs to Salt, is available from Fireside Fiction. Contrary to the rumors, she is probably not a secret android. Rachael is a World Fantasy Award nominee and Tiptree Award honoree. Her fiction has appeared in dozens of venues worldwide, including Lightspeed, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Strange Horizons, and all four Escape Artists podcasts. Follow her on Twitter @RachaelKJones.

Previous stories by Rachael K. Jones that appeared in Diabolical Plots are: “St. Roomba’s Gospel” in December 2015, “Regarding the Robot Raccoons Attached to the Hull of My Ship” co-authored with Khaalidah Muhammad-Ali and published in June 2017, “Hakim Vs. the Sweater Curse” in December 2017, and “The Day Fair For Guys Becoming Middle Managers” in April 2021. Her story “Makeisha In Time” was also reprinted in The Long List Anthology. If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.